24 Underwater Drones – The Boom in Robotics Beneath the Waves

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Underwater warriors

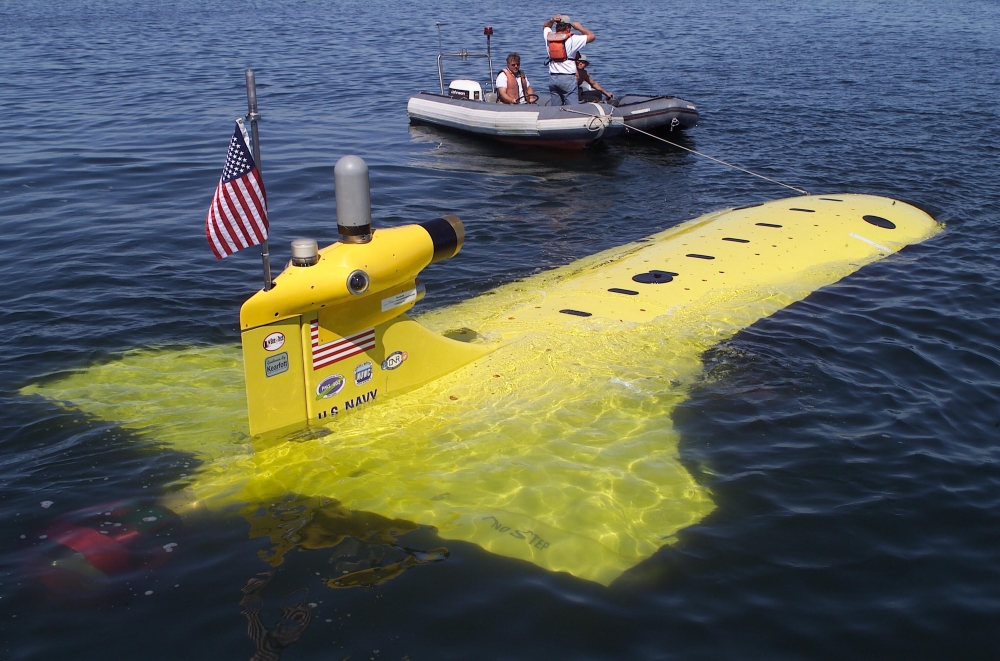

In September this year the US Navy created its first dedicated underwater drone unit: Unmanned Undersea Vehicle Squadron One, or UUVRON 1 for short. The US Navy sees underwater drones eventually being used in "every spectrum" of naval operations, from mine hunting and surveillance to humanitarian assistance and scientific research.

This image shows civilian contractors for the US Navy securing a Kingfish underwater vehicle, which can use side scan sonar to search for and investigate suspected naval mines and other objects of interest floating or on the sea floor.

Experimental Naval Drone

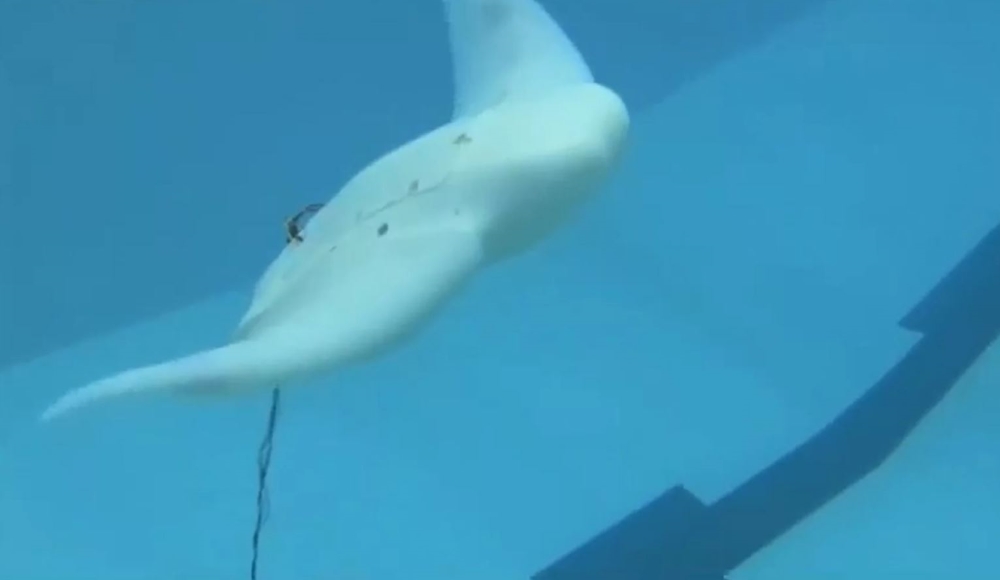

The US Navy's Naval Undersea Warfare Center (NUWC) has developed its Manta unmanned underwater vehicle as a modular test bed for autonomous underwater drone technologies.

The Manta UUV is over 30 feet long and carries a payload of up to five tons, which can include additional smaller underwater drones, for which it acts like a mother ship, and torpedo weapons.

Mantabot

The US Navy is also funding research into advanced underwater drone concepts like the swimming "Mantabot" developed at the University of Virginia, which uses silicone fins for swimming based directly on the cow-nosed ray, a species related to mantas.

The streamlined shape and swimming technique allows the drone to move quickly and quietly through the water using relatively little energy – a useful feature for underwater drones that would let them stay at sea for long periods without recharging.

Naval Drone Swarms

A recent briefing paper for the UK Parliament as it considered whether to modernize or scrap its Trident nuclear missile subs warned that advances in drone technology could soon make submarine warfare obsolete.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The report warned that swarms of cheap robot sub-hunters could blanket the oceans with acoustical and other sensors that could negate a submarine's ability to travel undetected underwater.

The US Navy has also experimented with autonomous boat drones to guard US ships and swarm enemy vessels.

Science Swarm

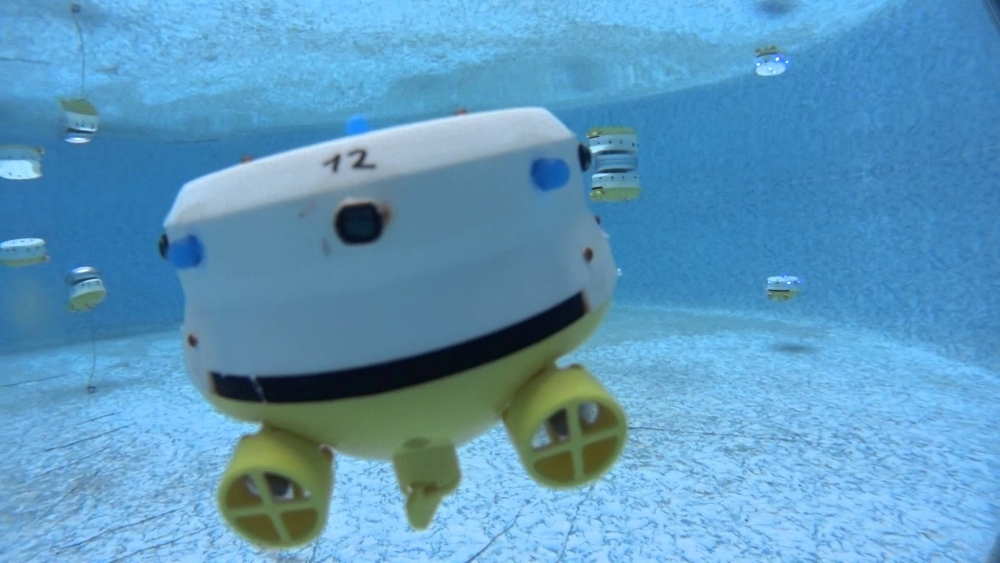

The world’s navies are not the only ones interested in swarms of underwater drones – scientists are too. Researchers at the University of Ganz in Austria have developed the CoCoRo swarm of more than 40 underwater bots to research how they can act together to accomplish various tasks underwater.

The autonomous drones in the CoCoRo swarm come in three different types, depending on their function, and use flashes of light to communicate.

Plankton Mapping Swarms

Scientists have also used swarms of underwater drones to investigate environmental events like plankton mating.

Researchers at the University of California-San Diego build a swarm of 16 autonomous underwater drones and dropped them off the coast.

The drones were told to stay at a depth of 33 feet, and to drift with and map the "internal waves" that enable by plankton species to mate.

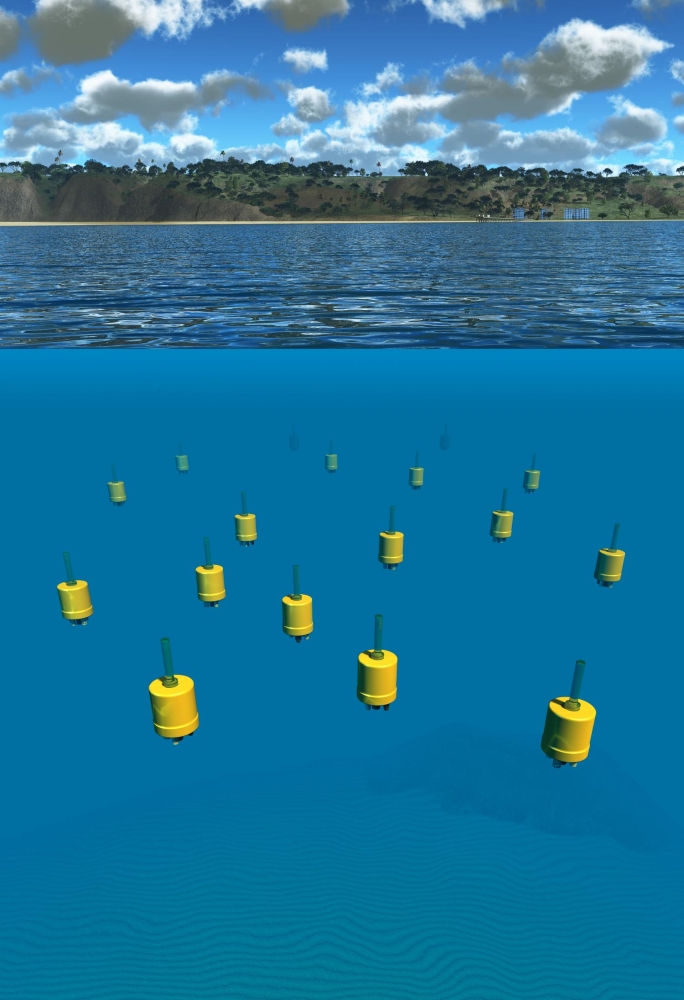

Floating Sensor Networks

Tech start-up Hydroswarm wants to build thousands of pumpkin-shaped underwater drones to map the oceans and act as a surveillance system for everything from oil pollution to illegal fishing to drug smuggling.

The EVE underwater drone – standing for Ellipsoidal Vehicle for Exploration – was developed by Sampriti Bhattacharyya, a mechanical engineer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Bhattacharyya says the EVE drone is designed to be used independently or as part of a swarm of underwater drones that could create a Google Maps for the oceans.

Underwater Robot Miners

Underwater robots designed to work in hazardous flooded mines were tested at a china-clay pit in the UK in October this year.

The EU-funded VAMOS project (Viable Alternative Mine Operating System) is developing three types of underwater drones to extract minerals from abandoned, flooded mine sites considered too dangerous or costly to access.

Mines deeper than the local water table usually fill with water unless it is pumped out – eventually they are abandoned and flood completely. The developers say it makes more sense to reopen an existed mine with robot miners, rather than excavate a new pit.

Drones Under the Ice

Underwater drones are used by scientists to explore some of the most remote regions of the oceans – including the coldest waters on earth, beneath Antarctica's ice shelves, where the temperature is a few degrees below the normal freezing point because of the salinity of the seawater.

Researchers have deployed torpedo-shaped drones from holes cut into the ice, equipped with radiometers to measure the light absorbed by clumps of ice algae growing on the bottom of the ice shelf.

Based on the drone measurements, scientists are able to estimate the total amount of algae growing on the ice – an important source of food in the ecosystems beneath the ice shelves.

Wartime Wreck Search

Underwater robots have also been used to search for the downed wrecks of American warplanes from World War II, as part of an effort to discover the final resting places of their crew.

"Project Recover" uses a variety of new underwater technologies, including autonomous underwater drones equipped with sonar and cameras, to make a thorough and regular search of the ocean floor for wartime plane wrecks, which are often very hard to spot.

In 2014, Project Recover divers using drones found two World War 2 warplanes in the islands of the Republic of Palau in the Western Pacific Ocean, and in 2016 they found two lost B-52 bombers near Papua New Guinea.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus