Ancient Jellyfish Embryos Curled Up Like Accordions

A set of spherical fossils, each fossil tinier than a grain of sand, is not what it seemed.

For years, researchers mistook these 537-million-year-old fossils for the embryos of arthropods, the group that includes insects, spiders and crabs. Now, a closer look reveals they really belong to the ancestors of jellyfish. What's more, they developed in very different ways than modern jellyfish, said Philip Donoghue, a paleobiologist at the University of Bristol in England.

This case of mistaken identity came down to minuscule lines in the surfaces of the fossils, which originally seemed to be similar to the segmentation lines on arthropod larvae. Donoghue and his colleagues were trying to figure out how these segments grew when they inadvertently discovered the lines weren't larval segments at all.

"We found that the segments aren't segments, just the in-folded rim of a cup-shaped sheath that would have enclosed an anemone-like organism," Donoghue told Live Science. [Cambrian Creatures: A Gallery of Weird Sea Life]

Early embryos

The finding upends speculation about the fossils, known as Pseudooides prima, that might explain arthropod diversity during the Cambrian period, which lasted from about 541 million to 485 million years ago. This period is known for an evolutionary eruption of biodiversity on Earth, and it produced many strange creatures resembling nothing alive on the planet today.

Fortunately, Donoghue said, some Cambrian rocks preserve rare finds: fossilized embryos. These sacks of cells, with no skeletal components, are extremely delicate and rarely fossilize, he said.

"They're little more than aggregations of cells, and you wouldn't have thought they could be fossilized at all," Donoghue said. It's lucky they have, he said, because the micro-fossils provide insights that paleontologists could get no other way.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The fossil embryos provide us with a direct insight into embryology of Cambrian animals and, in comparison to the embryology of living animals, we can deduce how embryology has evolved to create the body plans of living animals," he said.

A close look

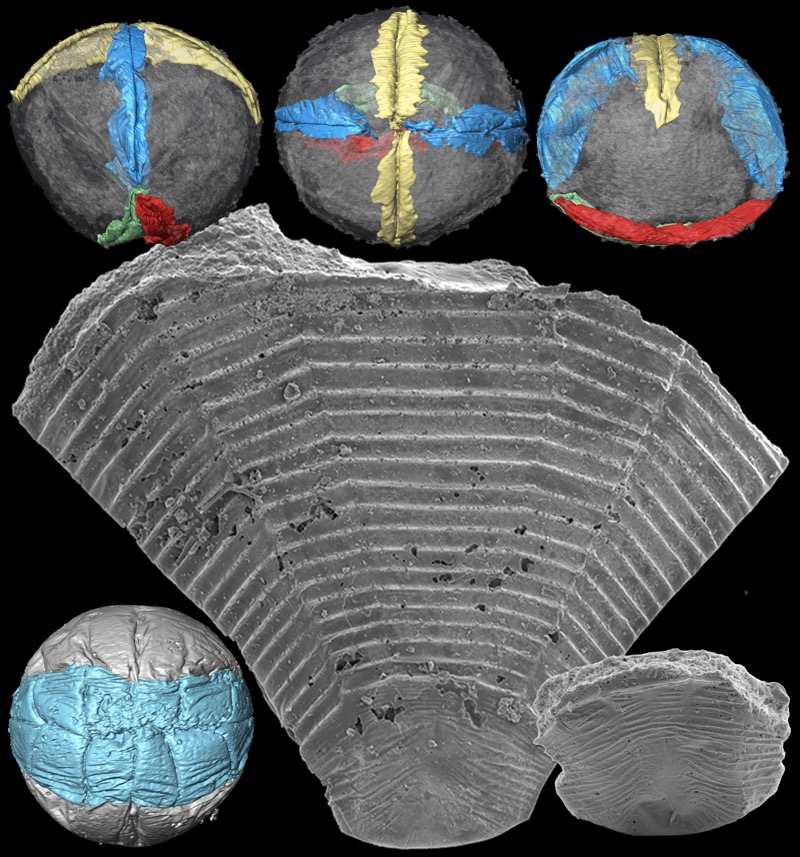

Donoghue and his team used scanning electron microscopy and synchrotron radiation X-ray tomographic microscopy to image 19 Pseudooides fossils from Shaanxi province, China. The latter technique uses a particle accelerator to beam pure X-rays at the interior of the fossils, enabling the resolution of features less than a thousandth of a millimeter in size, Donoghue said.

The ultra-detailed look at the fossil "segments" revealed that the lines don't penetrate through the entire fossil, but are instead surface folds that would have opened like an accordion. In fact, their development corresponded perfectly to another fossil found in the same samples, a cnidarian (the group that includes jellyfish) called Hexaconularia. But Hexaconularia doesn't really exist, the researchers found. It's just the adult form of Pseudooides.

The findings, published today (Dec. 12) in the journal Biological Sciences, reveal that Pseudooides developed directly from embryo to adult, which is very rare in modern jellyfish, Donoghue said. Almost all jellyfish today go through a larval form between their embryonic and adult stages. In the Cambrian, though, jellyfish life histories were more diverse, Donoghue said.

Pseudooides is weird compared with modern jellyfish in other ways. Most notably, it featured sixfold or tenfold symmetry, meaning it could be folded in six or 10 identical sections around its center. Today, Donoghue said, most jellyfish show fourfold symmetry.

"Evidently, some Cambrian jellyfish were organized in a very different way to their living counterparts, changing perception of the nature of ancestors," Donoghue said.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus