Album: Jellyfish Rule!

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Jellyfish Rule!

This giant red-hued jellyfish called Tiburonia granrojo was described by American and Japanese researchers in 2003. It grows up to 3.3 feet (1 meter) in diameter and lives at depths of 2,000 to 4,800 feet (650 to 1500 meters) in the ocean. First seen during submarine dives in 1993, the jellyfish is distinct in that it uses four to seven fleshy arms to capture food, rather than fine tentacles like other jellyfish.

Jellyfish Rule!

Tropical-dwelling box jellyfish have a cube-shaped body, and four different types of special-purpose eyes: The most primitive set detects only light levels, but another is more sophisticated and can detect the color and size of objects. The Australian box jellyfish is also deadly; each of its up to 60 tentacles carries enough toxin to kill 60 people.

Jellyfish Rule!

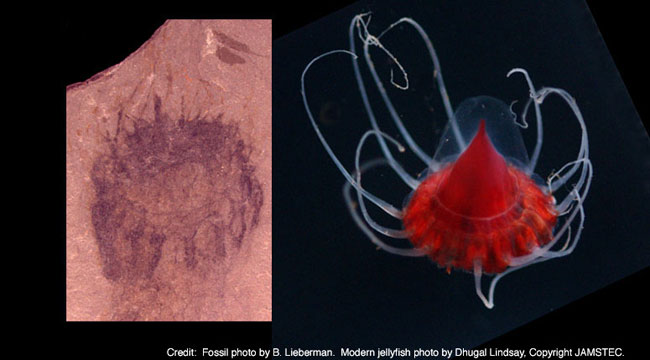

Fossil evidence of jellyfish dates back to the Cambrian Period, 500 million years ago. Cambrian fossil jellyfish shows similarity to the modern jellyfish (right), Periphylla. It was one of four different types of jellyfish dated back to the Cambrian by researchers in 2007. These ancient jellyfish showed the same complexity as modern jellyfish, meaning they either developed rapidly 500 million years ago, or today’s varieties are much older.

Stealthy Predator

The stealthy predator Mnemiopsis leidyi, also known as the sea walnut, uses tiny hairs, called cilia, to create a current which prey don't notice until they are sucked into its mouth region, surrounded by two large oral lobes. The sea walnut swims using fused cilia, which diffract light in many colors in this photo.

Jellyfish Rule!

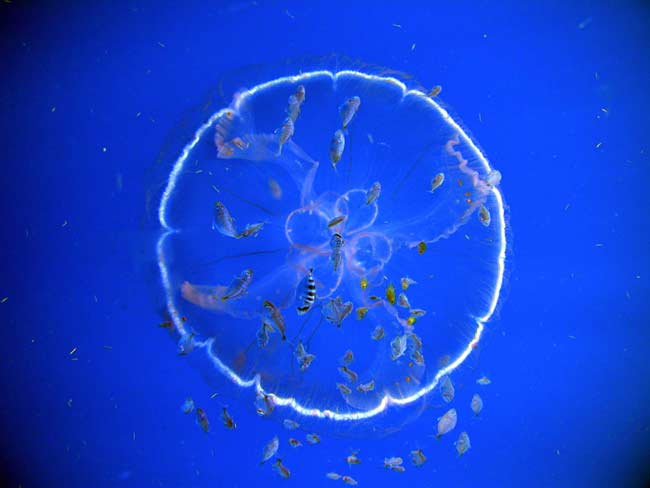

The saucer -like Aurelia aurita, or moon jellyfish is carnivorous and feeds on small plankton organisms, such as mollusks, crustaceans and ctenophores. It can be anywhere from 2 to nearly 16 inches (five to 40 centimeters) in diameter and is found in mostly warm and tropical waters.

Jellyfish Rule!

The moon jellyfish is common in many parts of the world, and it appears to have increased dramatically in Japanese waters in recent decades. Seen from a bird's eye view, a bloom of moon jellyfish appears as white swaths in a Japanese bay. In Japanese waters, its blooms have interfered with fishermen and power plants.

Mating Ritual

This image captures the courtship behavior of the box jellyfish Copula sivickisi. The male (top) and female (bottom) engage in a complex mating ritual unique among cnidarians (jellyfishes, hydroids, anemones, corals and their kin).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jellyfish Introductions

The moon jellyfish is believed to have been introduced into many new environments by ships, when the jellyfish's stationary developmental stage, called a polyp, attached to their hulls or came in via the ballast water, which ships dump once they arrive at their destination.

Jellyfish Rule!

Nemopilema nomurai, known as Nomura's jellyfish, can grow up to 6.6 feet (2 meters) in diameter. It is edible, though it hasn't caught on widely. When Nomura's jellyfish bloomed in 2005, some Japanese coped by selling souvenir cookies flavored with jellyfish powder, according to the New York Times.

Jellyfish Rule!

Blooms of Nomura's jellyfish have created serious problems in Japanese waters, including clogging fishing nets and stinging fishermen. Blooms have been recorded as far back as 1920, though they were rare events. But beginning in 2002, blooms have occurred nearly every year.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus