'Liquid' Cats and Old Men's Big Ears: Humorous Research Abounds at the Ig Nobels

But at the Ig Nobel Prize Ceremony, laughter is an important part of the process — maybe not the scientific process, but the process of selecting the prizewinners, who pursued research topics that made people laugh, and then made them think, according to the Ig Nobel organizers.

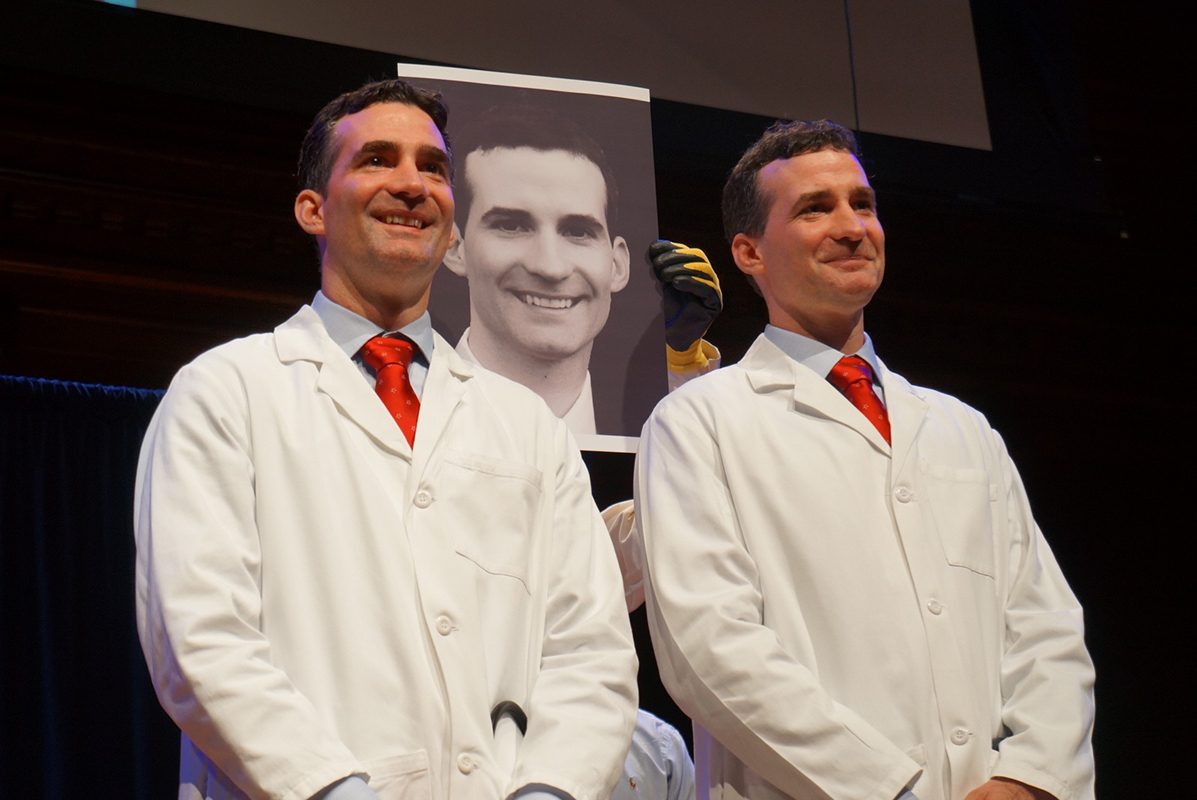

At the 2017 Ig Nobels, held here today (Sept. 14) in the Sanders Theatre at Harvard University, researchers representing five continents made an appearance to acknowledge the dubious achievement of acquiring an Ig Nobel. The evening was punctuated by commentary-free science experiments, a mini-opera about incompetence, ultra-brief lectures, and, of course, plenty of paper airplanes. [Watch the 27th First Annual Ig Nobel Prize Ceremony]

Top-hatted master of ceremonies Marc Abrahams, founder of the Ig Nobels and the editor of the science humor magazine "Annals of Improbable Research," announced winners in 10 categories: Physics, Peace, Economics, Anatomy, Biology, Fluid Dynamics, Nutrition, Medicine, Cognition and Obstetrics. Each winner received a coveted (and handcrafted) Ig Nobel statue topped with a red question mark, commemorating the year's theme of "Uncertainty." They also received 10 trillion dollars — Zimbabwean dollars, that is, delivered in a single bill and worth about 4 U.S. cents.

Winners were handed their prizes by obliging Nobel laureates and then invited to say a few words. But not too many — after 60 seconds, an adorable 8-year-old girl named "Miss Sweetie Poo" would join them onstage, and repeat "Please stop, I'm bored!" until the long-winded winners stopped talking. [The 10 Ig Nobel Awards of 2017]

Not that they didn't have plenty to talk about. Their research delved into fascinating territory: whether cats are both a solid and a liquid, why old men's ears are so darn big, how interacting with a live crocodile can affect a person's affinity for gambling, and why some people are disgusted by cheese, to name just a few.

Some acceptance speeches were followed by brief demonstrations of the research findings, such as the study that won the Fluid Dynamics Prize, which showed how a cup of coffee sloshes and spills when the person carrying it is walking backward.

Another demonstration was performed by a co-author of the study that won the Peace Prize; he brought an unusual musical instrument onstage to spotlight findings that showed how sleep apnea and snoring could be effectively treated by playing a didgeridoo.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Other scientists delivered 24-second lectures about their research and followed up with a seven-word summary, such as, "Robots that talk are perceived as stupid," and "Uncertainty is the only sure thing. Perhaps."

Abrahams announced that a live demonstration with a vampire bat had been planned to showcase a winning study about the first evidence of vampire bats feeding on people. But, he said, the bat was "not where we left it." He recommended that if anyone came across the wayward bat, they should notify an usher.

Before long, the evening wound to a close. After all the prizes were awarded and the final notes of the opera were sung, everyone gathered together one last time, for the traditional Ig Nobel "Goodbye, Goodbye" speech, which was as heartfelt as it was brief. The winners may not have had much time onstage to talk about their noteworthy research, but as Abrahams put it, "Their achievements speak for themselves all too eloquently."

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus