Dangerous Dance: Hurricanes' Dalliance May End in 'Cannibalism'

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

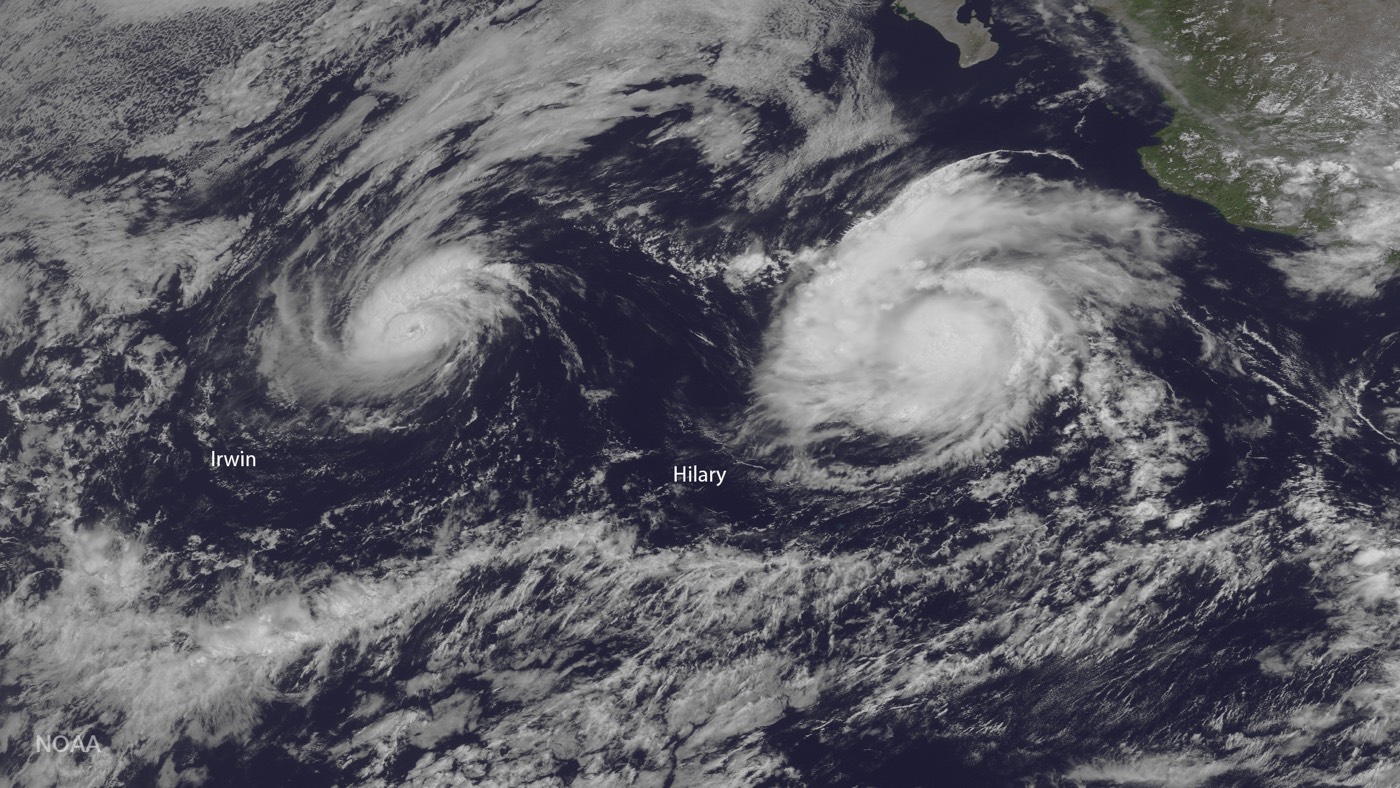

Several storms currently swirl in the Pacific Ocean, with two hurricanes on course for a do-si-do that may end in one dance partner cannibalizing the other.

The bigger storm, Hurricane Hilary, is located several hundred miles south of the Baja California peninsula and has wind speeds of up to 105 mph (165 km/h). Hurricane Irwin is farther west of Hilary and has been weakening, with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h).

Currently, the hurricanes aren't threatening any coastal areas, but they might get locked in a strange dance step known to meteorologists as the Fujiwhara effect. [A History of Destruction: 8 Great Hurricanes]

The National Hurricane Center's latest update says Irwin is expected to have some "binary interaction" with Hilary during the next two days. A binary interaction —another name for the Fujiwhara effect —happens when two hurricanes get very close to each other, within about 800 miles (1,290 km), so that their vortices, the spinning centers of the storms, interact.

Two vortices spinning in the same direction will start to orbit around a single center of mass if they get close enough to each other. With two hurricanes that are similar in strength, this center of mass will be the midpoint between the two storms. But if one vortex is stronger, that storm will be closer to the center of the action and could swallow the smaller storm. In this case, Irwin is the smaller storm, and it is expected to pinwheel around the eastern edge of Hilary in the coming days, according to the National Hurricane Center.

Oddly enough, a similar scenario already played out earlier this week, farther west in the Pacific, with Typhoon Noru and Tropical Storm Kulap. (The terms hurricane, typhoon and cyclone all refer to the same weather phenomenon, just in different locations.) It's rare to witness two Fujiwhara effects in the same ocean within such a short amount of time, according Jonathan Erdman, a meteorologist at Weather.com.

Typhoon Noru became the first typhoon of 2017. After a dance with tropical storm Kulap, Noru cannibalized its weaker counterpart and moved on. When Noru was spotted yesterday (July 25) by NASA's Aqua satellite, the storm had maximum sustained winds of about 92 mph (148 km/h). The Joint Typhoon Warning Center forecasted that the storm will move west over the next several days and approach the island of Iwo To, southeast of Tokyo, at the end of the week, and will be at typhoon strength.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fujiwhara effects have occurred in major hurricanes before. According to Climate Central, the phenomenon is rare in the Atlantic Ocean, but it occurred with Superstorm Sandy when the hurricane interacted with the vortex of a larger extratropical storm. The dance between these two vortices helped pull Superstorm Sandy ashore along the eastern United States, where it caused record flooding and damage.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus