'Stalker' Velociraptor Relative Sported Feathers, Serrated Teeth

About 71 million years ago, a feathered dinosaur that was too big to fly rambled through parts of North America, likely using its serrated teeth to gobble down meat and veggies, a new study finds.

The newly named paleo-beast is a type of troodontid, a bird-like, bipedal dinosaur that's a close relation of Velociraptor. Researchers named it Albertavenator curriei, in honor of the Canadian province where it was found (Alberta), its stalking proclivity (venator is Latin for "hunter") and Philip Currie, a renowned Canadian paleontologist.

"The delicate bones of these small feathered dinosaurs are very rare," lead study researcher David Evans, the senior curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Royal Ontario Museum, said in a statement. "We were lucky to have a critical piece of the skull that allowed us to distinguish Albertavenator as a new species." [Photos: Velociraptor Cousin Had Short Arms and Feathery Plumage]

Researchers found two fossilized pieces of A. curriei’s forehead in the Horseshoe Canyon Formation, located in Alberta's Red Deer River Valley, south of Edmonton. A larger fossil, likely belonging to an adult, was found in 1993, and a smaller one, probably from a half-grown individual, was discovered in 1996, Evans said. Both fossils were stored at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta, where they remained, unstudied, until the researchers in the new study decided to investigate them.

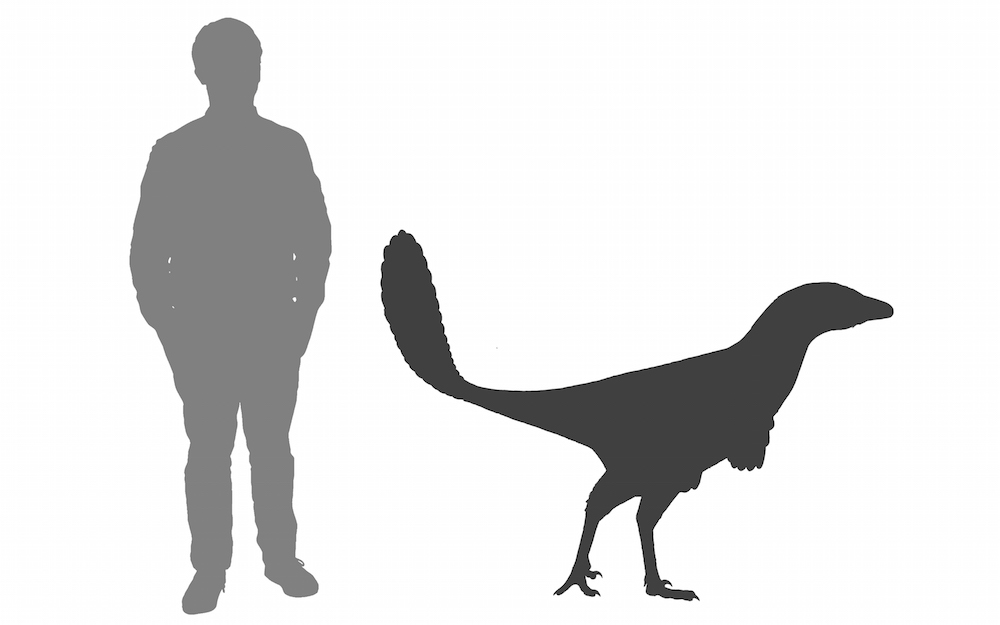

During its lifetime, the larger A. curriei individual likely stood at the chest or waist height of a full-grown person, and would have weighed about 132 lbs. (60 kilograms), Evans told Live Science in an email. Its peculiar, serrated teeth suggest it might have been an omnivore, he added.

"We hope to find a more complete skeleton of Albertavenator in the future, as this would tell us so much more about this fascinating animal," Evans said in the statement.

The two fossils are extremely rare, as finding non-dental troodontid material in North America dating to the late Cretaceous (which lasted from 72.1 million to 66 million years ago) is almost unheard of, the researchers wrote in the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In fact, there are only four known species of troodontid from North America dating to the late Cretaceous: Troodon formosus from Montana, Stenonychosaurus inequalis from Alberta, Pectinodon bakkeri from Wyoming and Talos sampsoni from Utah, the researchers said.

At first, paleontologists thought that the A. curriei fossils belonged to T. formosus, a close relative that lived about 76 million years ago. However, an analysis of the forehead fossils showed that the newfound specimens were shorter and more robust than those of T. formosus, the researchers said.

To complicate matters, the teeth from A. curriei and T. formosus look the same, meaning they can't be used to distinguish the two species. This finding suggests that some of the hundreds of isolated teeth attributed to T. formosus might actually belong to A. curriei, the researchers said.

"This discovery really highlights the importance of finding and examining skeletal material from these rare dinosaurs," study co-researcher Derek Larson, an assistant curator of the Philip J. Currie Dinosaur Museum, said in the statement.

Given the difficulty of identifying A. curriei, it's likely that other small dinosaurs are escaping the notice of paleontologists, the researchers said. If that's the case, then there was even greater dinosaur diversity in North America than previously realized, they added.

"It was only through our detailed anatomical and statistical comparisons of the skull bones that we were able to distinguish between Albertavenator and Troodon," study co-researcher Thomas Cullen, a doctoral student of paleontology at the University of Toronto, said in the statement.

Currie, the species' namesake, was not a researcher on the study, but both specimens were found in the badlands around the Royal Tyrrell Museum, which Currie helped establish in the early 1980s. This is the second newfound dinosaur species from Alberta that is named for Currie. The other, Epichirostenotes curriei, also from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation, is an oviraptorosaur, another type of bird-like dinosaur.

The study was published online today (July 17) in the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus