200,000-Year-Old 'Baby Tooth' Reveals Clues About Mysterious Human Lineage

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

DNA in a fossil from a young girl has revealed that a mysterious extinct human lineage occupied the middle of Asia longer than previously thought, allowing more potential interbreeding with Neanderthals, a new study finds.

Although modern humans are the only surviving human lineage, other hominins — which include modern humans, extinct human species and their immediate ancestors — once lived on Earth. These included Neanderthals, the closest extinct relatives of modern humans, as well as the Denisovans, who lived across a region that might have stretched from Siberia to Southeast Asia.

In 2010, researchers analyzed DNA from fossils to reveal the existence of the Denisovans, suggesting the lineage shared a common ancestor with Neanderthals. However, the Denisovans were nearly as genetically distinct from Neanderthals as Neanderthals were from modern humans, with the ancestors of Denisovans and Neanderthals splitting about 190,000 to 470,000 years ago. [Denisovan Gallery: Tracing the Genetics of Human Ancestors]

The 2010 study also revealed that the Denisovans might have interbred with modern humans thousands of years ago just as Neanderthalsdid. Subsequent research suggested that genetic mutations from Denisovanshave influenced modern human immune systems, as well as fat and blood sugar levels.

However, much remains unknown about the Denisovans, since all fossil evidence of them until now was limited to just three specimens: one finger bone and two molars. All three fossils were unearthed from Denisova Cave, after which the Denisovans are named, in the Altai Mountains in Siberia.

Now, scientists have revealed that they have a fourth Denisovan fossil — a "baby tooth" that likely fell from the jaw of a 10- to 12-year-old girl, said study lead author Viviane Slon, a paleogeneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

"Any additional Denisovan individual that we can identify at this point is very exciting for us," Slon told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

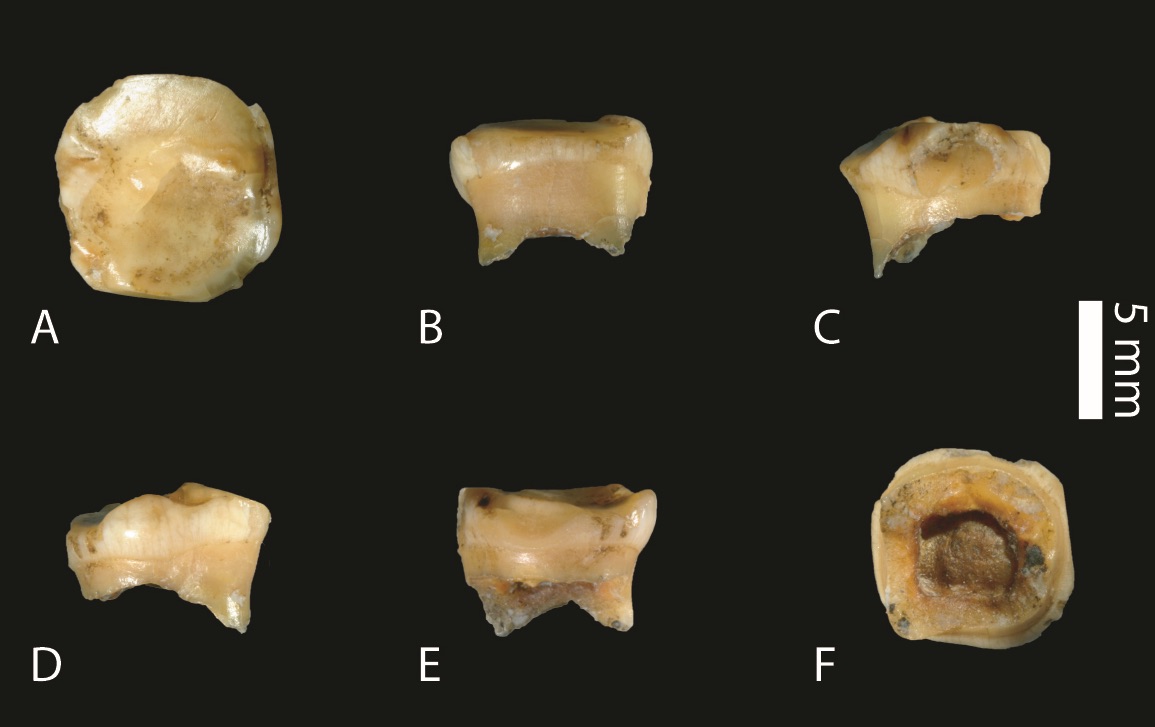

The crown of the "baby" molar was almost completely worn away when researchers unearthed it. To help preserve the fossil, the researchers used 3D X-rays of the tooth to help find the best way to extract as little powder from the molar as possible. Next, they analyzed what little surviving DNA they could from about 10 milligrams of tooth powder, confirming that the fossil belonged to a Denisovan girl.

The deep layer of sediment in which this molar was found ranges from 128,000 to 227,000 years old. This age makes the tooth one of the oldest human specimens discovered in central Asia to date, and about 50,000 to 100,000 years older than the first known Denisovan fossil.

"This would indicate that Denisovans were present in the Altai area for a very long time — at least as long as modern humans have been in Europe, if not much more," Slon said. Such a long span of time increases the chances that the Denisovans and the Neanderthals may have interacted and interbred, the researchers added.

These new findings, combined with previous data, suggest that there may have been low levels of genetic diversity among the Denisovans, comparable to the lower range of modern human genetic diversity seen among small or secluded populations.

"The low genetic diversity we infer for the Denisovans can most probably be linked to their small population size," Slon said. "This is similar to what has been inferred for Neanderthals. Both groups of archaic hominins seem to have had a far smaller population size than humans today."

Still, the researchers noted that because all four Denisovan fossils unearthed to date come from the same place, it is possible that they represent an isolated population and that Denisovan genetic diversity across

their entire geographic range was greater than that seen in these isolated samples. Additional fossils from Denisovans from other locations would help scientists more comprehensively gauge Denisovans' genetic diversity across space and time, Slon said.

The scientists detailed their findings online July 7 in the journal Science Advances.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus