Tardigrades: Facts about one of the hardiest animals on Earth, and beyond

Discover interesting facts about tardigrades — near-microscopic animals that can survive freezing temperatures, crushing pressures and even the vacuum of space.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

• Tardigrades are hardy enough to survive large asteroid impacts and even supernova blasts.

• Water bears have survived all five mass extinctions on Earth since they first evolved about half a billion years ago.

• Tardigrades may protect themselves from harmful UV rays by making themselves fluorescent.

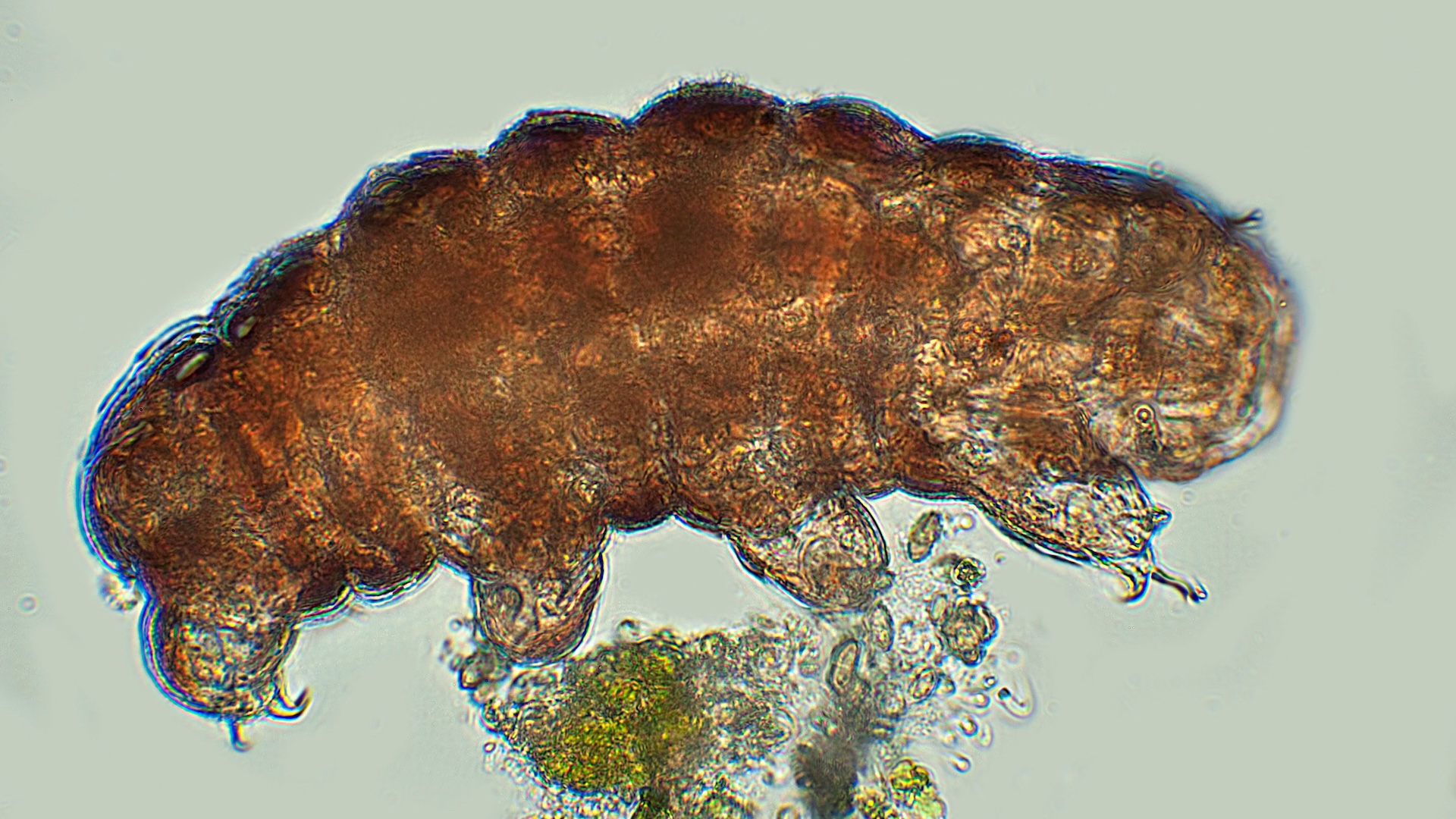

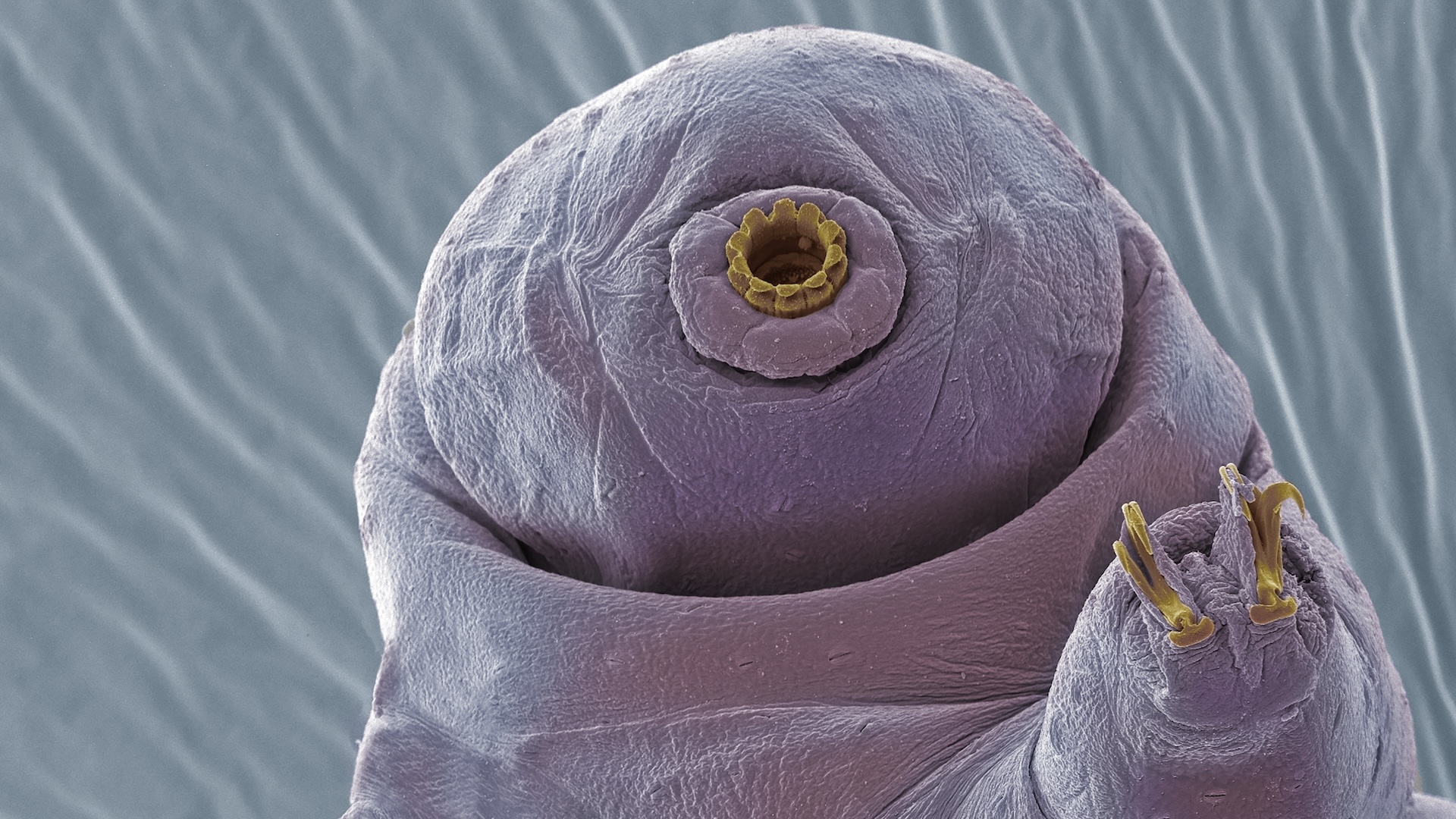

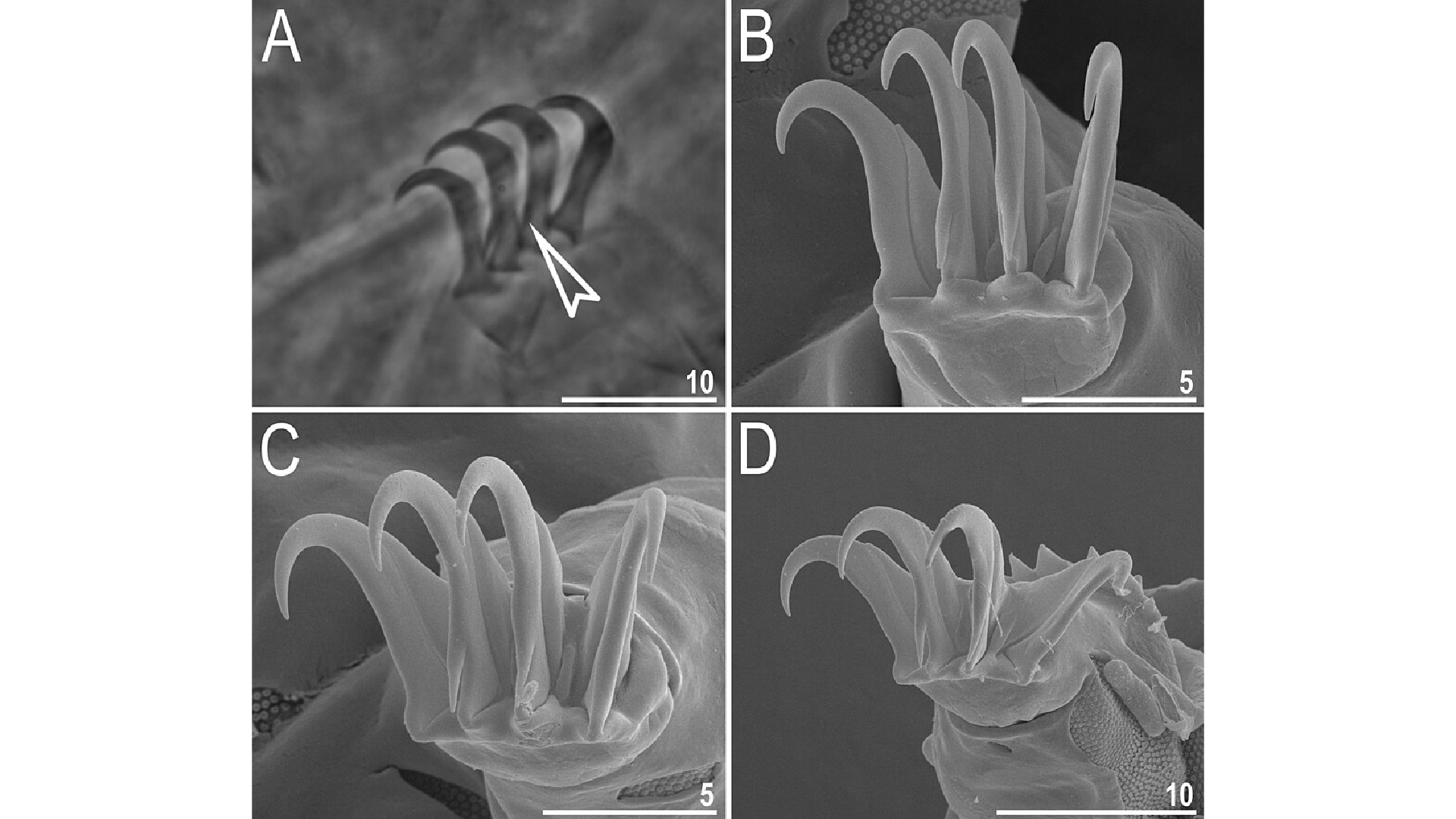

Tardigrades, often called water bears or moss piglets, are tiny aquatic animals. Under a microscope, you can see their plump, segmented bodies and flat heads. They have eight legs, each tipped with four to eight claws, and look a bit like the caterpillar from "Alice in Wonderland." Though tardigrades are cute, they are also nearly indestructible.

Tardigrades were discovered in 1773 by the German zoologist Johann August Ephraim Goeze, who nicknamed them "little water bears." Three years later, Italian biologist Lazzaro Spallanzani named the group "Tardigrada," or "slow stepper," for the way they move.

Scientists have identified about 1,300 tardigrade species. They can survive punishing heat, freezing cold, ultraviolet radiation and even outer space. They do this by becoming dried-out little balls, called "tuns," and almost stopping their metabolism (the way they get energy from food), reviving only when conditions are better. In fact, these tough little water bears will probably survive long after humanity is gone, research has found.

5 fast facts about tardigrades

- Where they live: Water bears, true to their name, live in water, from oceans to drops of water on plants. They can live high in the mountains and deep in the ocean.

- What they eat: Tardigrades mostly eat plants and algae. Some species eat other, smaller creatures, like microscopic worms and tiny, wheel-shaped animals called rotifers.

- What makes them special: They curl up into dried-up balls that can survive boiling water, freezing cold and outer space. This is called a tun state.

- How big they get: They grow to about the size of the period at the end of this sentence.

- How long they live: Water bears may survive up to a century in their tun state. Outside their tun state, they live between 3 months and 2.5 years.

Everything you need to know about tardigrades

Where do tardigrades live?

Water bears live anywhere there's liquid water, including oceans, freshwater lakes and rivers, and the water film that coats mosses and lichens on land.

They can live above 19,600 feet (6,000 meters) in the Himalayas down to ocean depths of more than 15,000 feet (4,700 m), according to the University of Michigan's Animal Diversity Web (ADW).

Related: Tardigrades probably see in black and white

Not all tardigrades live in extreme environments, but they can survive extreme conditions that would kill most other life-forms.

Tardigrades don't live in or on humans, and they are not dangerous to us.

What do tardigrades eat?

Most tardigrades suck fluids from cells in plants, algae and fungus. They use needle-like structures in their mouths to pierce cell walls and vacuum up the liquid inside.

However, some species can consume tiny moving creatures, such as nematodes and even other tardigrades.

What makes tardigrades so indestructible?

Tardigrades can live in a wide variety of environments because they enter an almost death-like state called cryptobiosis. To enter cryptobiosis, a tardigrade squeezes out more than 95% of the water from its body, retracts its head and legs, and curls into a dried-out tun.

Four things can trigger cryptobiosis: being dried out, freezing, not having enough oxygen and having too much salt.

During cryptobiosis, a tardigrade slows its metabolism to a tiny fraction of normal levels. Unique proteins protect its cells from damage. When a tardigrade expels its body's water, these proteins form a tough, glass-like cocoon around the tardigrade's cells. This keeps its cells safe while the tardigrade is a tun. Then, it can reanimate in water when conditions are more hospitable. Tardigrades evolved this ability hundreds of millions of years ago — perhaps even to survive mass extinctions, a study found.

"Tardigrades are fascinating little beasties," Sandra McInnes, a tardigrade researcher with the British Antarctic Survey, previously told Live Science. "Tardigrades have this ability to cope with extreme environments by shutting down their metabolism. This ability to cope with drying out or freezing is what gives them their durability in the Antarctic."

Tardigrades can spend decades, or even a century, in a tun state before reviving. That means tardigrades can technically live a century or more.

However, tardigrades do have a fatal weakness: They wilt in hot water. Tardigrades can die within a day in water temperatures of about 100 degrees Fahrenheit (38 degrees Celsius), one study found.

Sandra McInnes is a tardigrade researcher with the British Antarctic Survey. She also is an associate editor dedicated to tardigrade-related manuscripts at the journal Zootaxa.

How big are tardigrades?

Tardigrades can be seen with the naked eye, but just barely. They range from 0.002 to 0.05 inch (0.05 to 1.2 millimeters) long, but they usually don't get bigger than 0.04 inch (1 mm) long, according to the World Tardigrada Database.

A tardigrade's body is made up of only 1,000 cells. In comparison, the human body has many trillions of cells.

What do tardigrades look like?

If you look under a microscope into the tardigrade's tiny body, you won't find any bones. Instead, tardigrades have a fluid-filled compartment called a hemolymph. Similarly to human blood, the hemolymph is filled with nutrients.

Although water bears lack a spinal cord, they have a nervous system, according to the 2004 book "Forest Canopies." This sends signals between the tardigrade's brain and body and acts similar to a vertebrate's spinal cord.

Water bears have a complete digestive system but no circulatory or respiratory system. Instead, oxygen from the water enters their bodies through their outer coats. To pump nutrients and oxygen around their bodies, they squeeze their muscles.

What extremes can tardigrades survive?

Tardigrades in a tun state can withstand temperatures as low as minus 328 F (minus 200 C) and hotter than 300 F (149 C). They can also survive some exposure to radiation and boiling liquids and up to six times the pressure of the deepest part of the ocean, according to the Science Education Resource Center at Carleton College in Minnesota.

When dehydrated, some tardigrade species survived a 10-day trip into low Earth orbit and returned to Earth unharmed by solar ultraviolet radiation or the vacuum of space.

Dried-out tardigrades were shot from a high-speed gun, traveling nearly 3,000 feet per second (900 meters per second) and surviving extremely high pressure.

But that research found that several thousands of tardigrades that were in their ball-like tun state and carried on the Israeli lunar mission Beresheet would not have survived after the lander crashed on the moon on April 11, 2019. The shock pressure of the metal lander hitting the moon would've been "well above" the limits tardigrades could survive.

Tardigrade taxonomy

Here is the taxonomy, or classification, for the tardigrade, according to the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS):

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Bilateria

Infrakingdom: Protostomia

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Superphylum: Ecdysozoa

Phylum: Tardigrada

Tardigrade pictures

This illustration depicts the tardigrade's long gut (gray) and ovary above (yellow).

Discover more about tardigrades

—1st tardigrade fossils ever discovered hint at how they survived Earth's biggest mass extinction

—Tardigrades survive being dried out thanks to proteins found in no other animals on Earth

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

- Tia GhoseEditor-in-Chief (Premium)

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus