7 unanswered questions about sharks

Here are seven shark mysteries scientists still don't have the answer to.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Sharks are iconic creatures, but researchers know remarkably little about them. For instance, although scientists know of more than 400 shark species, many of these big fish fare poorly in captivity, making it difficult to observe their mating, navigational, learning and social (or anti-social) behavior. Here are seven mysteries that scientists have yet to solve about sharks.

1. How do sharks navigate?

The open ocean has few visual cues, so how do sharks know where they're going? Some sharks travel great distances, such as the great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) that swim across the Indian Ocean, from the west coast of Australia to South Africa, said Andrew Nosal, a marine biologist and shark scientist at University of San Diego.

"It is an enduring mystery how sharks find their way through the ocean, which environmental cues they use, and how exactly those cues are detected and integrated," Nosal told Live Science.

Some sharks may use Earth's magnetic field to help them generate a mental map and compass, a May 2021 study published in the journal Current Biology suggested. In that study, researchers found that wild bonnetheads (Sphyrna tiburo) were able to orient themselves to that applied magnetic field, suggesting they use such fields to navigate.

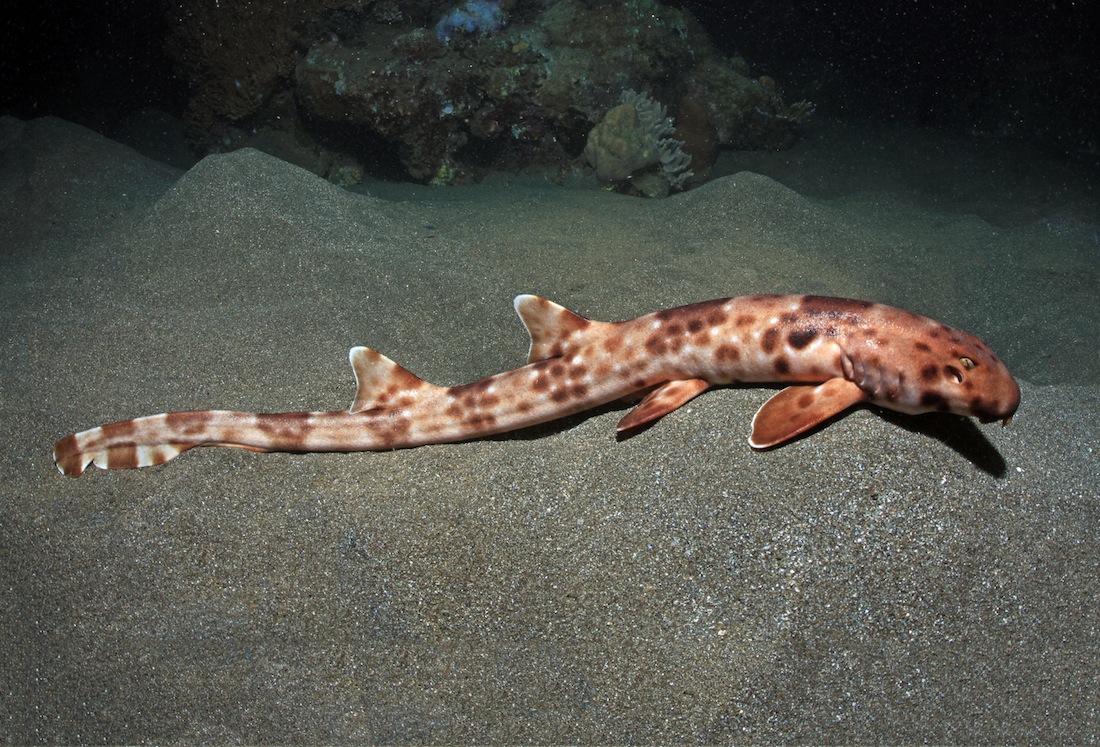

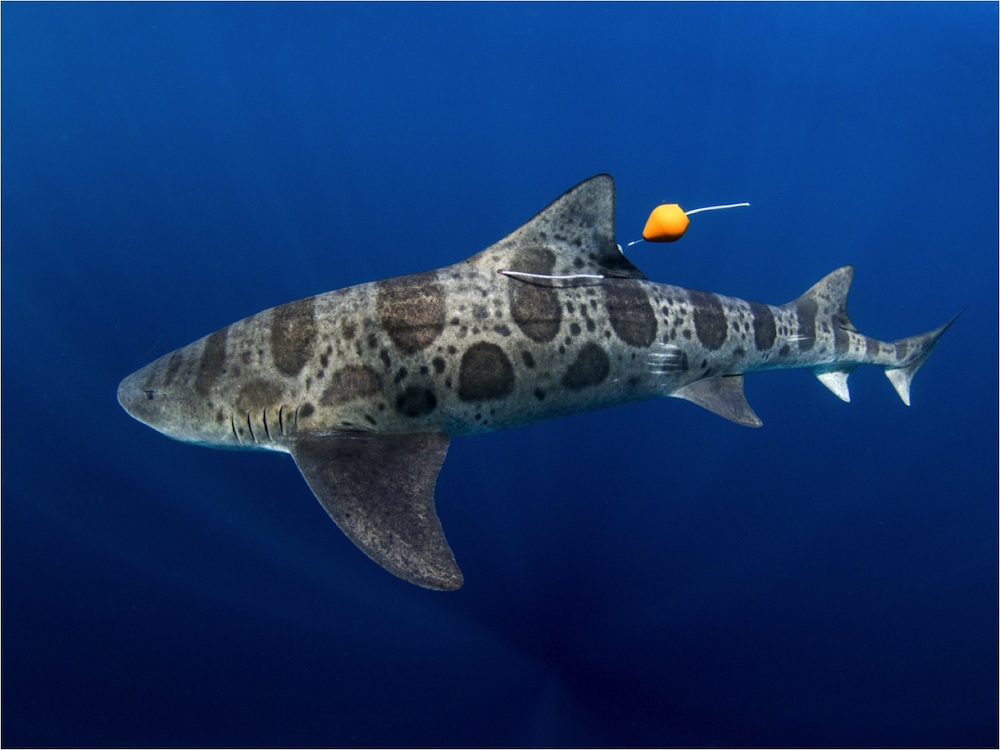

Olfaction (smell) may be another navigational tool that some sharks use, according to a 2016 study by Nosal and colleagues on leopard sharks (Triakis semifasciata). But perhaps other factors — such as water temperature, sound and even vision (to some extent) — may help sharks navigate the deep, Nosal said.

2. How many species exist?

Researchers are still discovering new species of shark, especially from the deep ocean.

"The deep ocean is so vast and we've spent so little time studying it, that it feels like every time a scientist goes out and does some fishing or trolling or even goes to a fish market in a little known place, they find a new species of shark," Christopher Lowe, a professor of marine biology and director of the Shark Lab at California State University, Long Beach, told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Moreover, sharks can range greatly in size, from as small as a cigar (like the American pocket shark) to as large as a school bus (such as the whale shark, a plankton feeder). They also live in diverse habitats, so a newfound species could be uncovered anywhere, Nosal said.

Related: Biggest sharks in the world

3. Why do sharks migrate?

It's clear that many sharks migrate seasonally, different tracking studies show. In other cases, as with the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier), species have "partial migration, where some individuals have a propensity to be homebodies and others have a propensity to migrate," Lowe said. "And we don't know why."

Related: Why 10,000-plus sharks are hanging out in Florida waters

For the critically endangered school shark (Galeorhinus galeus), females have a three-year migration, returning to their reproductive spot every third year, likely to ovulate and gestate, a March 2021 tracking study led by Nosal in the Journal of Applied Ecology found.

However, why the majority of these migrations happen is still a mystery. Do sharks migrate for food, mating, temperature or perhaps a mixture of all three? It's hard to say. Only by studying vast numbers of a single species of shark can researchers find overall trends and perhaps tease out the reasons behind each migration, Nosal said.

4. What are they doing underwater?

It's anyone's guess what sharks are doing deep in the ocean, said Gregory Skomal, a fisheries biologist with the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries. Trackers can tell scientists where the sharks are swimming, but once the fish dive deep into the water, it's hard to follow them without disrupting their behavior, he said.

"We have plenty of data on white sharks that shows that some of them go out to the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, wander around and dive down to depths as great as 3,000 feet (900 meters) every day," Skomal told Live Science. "But we don't have any clue what they're actually doing there."

Once, Skomal and his colleagues sent down an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) to spy on great white sharks at night. The footage suggested that the sharks were resting. "I dare not say 'sleep' because it's hard for us to determine if and when these sharks sleep," Skomal said.

In another case, researchers found that grey reef sharks (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos) surf on updrafts of water, likely to save energy, according to a June 2021 study in the Journal of Animal Ecology.

5. What role do sharks play in the ecosystem?

Most people say that sharks are apex predators and are essential for maintaining balance in the food web. But not all sharks are at the top of that web, Nosal said.

"It's still a mystery exactly how sharks fit in," he said. "Surely they are important, and many species are indeed apex predators. But food webs are very complicated."

Many shark habitats are so damaged, it's hard to know how they functioned before disruptions, such as overfishing and habitat destruction, Lowe said. However, a few places around the world, including Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands (whose inhabitants were relocated due to the effects of nuclear bomb testing) give a hint as to how shark habitats should look, Lowe said. Because people essentially abandoned the islands, the ecosystems have recovered.

Lowe visited the Bikini Islands recently. Without downplaying the terrible effects of nuclear testing, "for me, it was this amazing experience because people hadn't been there, really, for 50 years. Even foreign fishermen would avoid that place because of their fear of the radiation," he said. "For me it was like Jurassic Park."

How smart are sharks?

6. How smart are sharks?

Studies on shark brains suggest the fish are complex beings, but in what ways are they smart?

Sharks don't have many folds in their forebrains (an area associated with decision making and reasoning in people), but they do have lots of folds in their cerebellum (a region associated with coordinating body movements), said Jelle Atema, a professor of biology at Boston University Marine Program. And shark brains may have unique abilities when it comes to smell. Atema has studied sharks' two well-developed olfactory bulbs, he said.

In a 2010 study in the journal Current Biology, Atema and his colleagues found that dusky smooth-hound sharks (Mustelus canis) turned toward odors stimulated first in their nares (nose), even if the second smell stimulation offered to them was higher in concentration. This trick may help the sharks stay connected to an odor plume, even if another smell in the busy ocean is of higher concentration, he said.

Anecdotally, Lowe has annually tracked tiger sharks to French Frigate Shoal in the Northwest Hawaiian Islands, where the sharks chow down on blackfoot albatross chicks learning to fly. "We found that literally a week before the birds start to fledge, the sharks start showing up," Lowe said. "We observed some individuals eating four to six albatross chicks a morning." As soon as the last chicks fledge, the sharks leave, he said. That suggests sharks' "smarts" include detailed memories about the time and location of events, at least when it comes to food.

7. Are sharks social animals?

Some sharks swim in schools of various sizes, and others gather in groups of hundreds to thousands. But it's unclear whether sharks are attracted to one another or whether they're simply in the same spot because it's a nice location with good temperatures and food availability, Nosal said.

"Almost certainly, it's going to be a combination of the two," he said. "But we don't really know the extent to which sharks are social animals. There's more and more evidence that they are, but the details are forthcoming."

Related: Surprise! Sharks have social lives.

This story was originally published on June 29, 2016 and updated on July 16, 2021 to include additional studies and comments from Chris Lowe.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus