Stomach Sucker: How Does New Weight-Loss Device Work?

The Food and Drug Administration recently approved a weight-loss device that may sound like something out of a science-fiction movie: a small tube inserted into the stomach allows patients to drain a portion of their gut's contents before the body absorbs those calories.

The device, called AspireAssist, was approved by the FDA after a year-long clinical trial on 171 people, 111 of whom underwent a procedure to place the device. The remaining 60 people were a part of the control group and did not wear a device. The researchers found that the patients with the device lost, on average, 31 pounds after one year.

But not all weight-loss experts think the device is a game-changer. Some critics argue that much more research is needed to prove such an approach works. In addition, there are concerns that the act of removing food from the stomach after eating may induce eating disorders similar to bulimia. [The Best Way to Lose Weight Safely]

How AspireAssist works

While the device may seem novel, the procedure for placing it is actually one that many doctors are quite familiar with.

It's the standard procedure for placing a feeding tube into the stomach, said Dr. Shelby Sullivan, the director of bariatric endoscopy at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and one of the researchers involved with the clinical trial on the device.

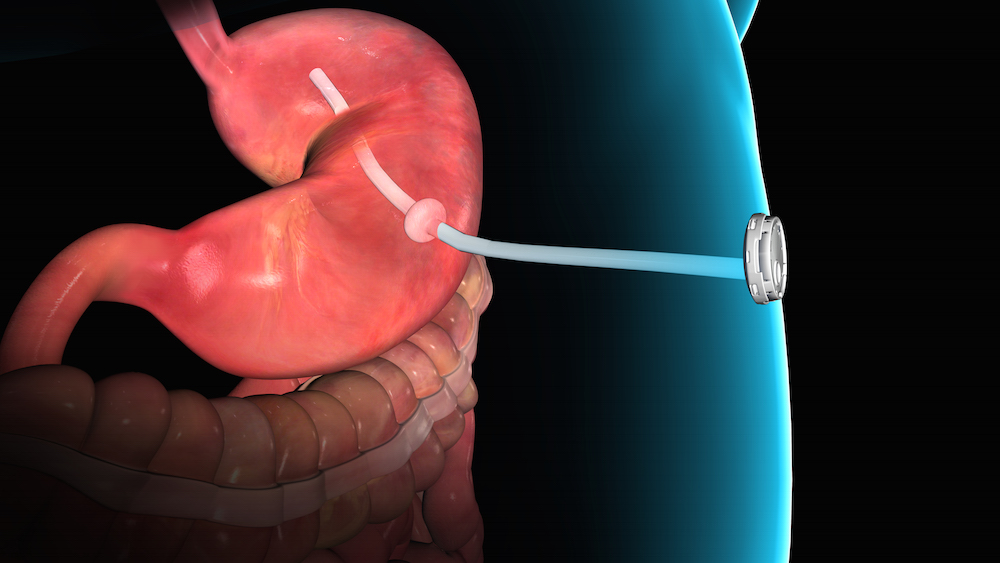

The procedure, which can be performed by gastroenterologists, as opposed to surgeons, takes about 15 minutes, Sullivan said. Patients are put under twilight anesthesia for the procedure. The tube is inserted through the mouth using an endoscope, and pulled through a small incision in the abdomen.

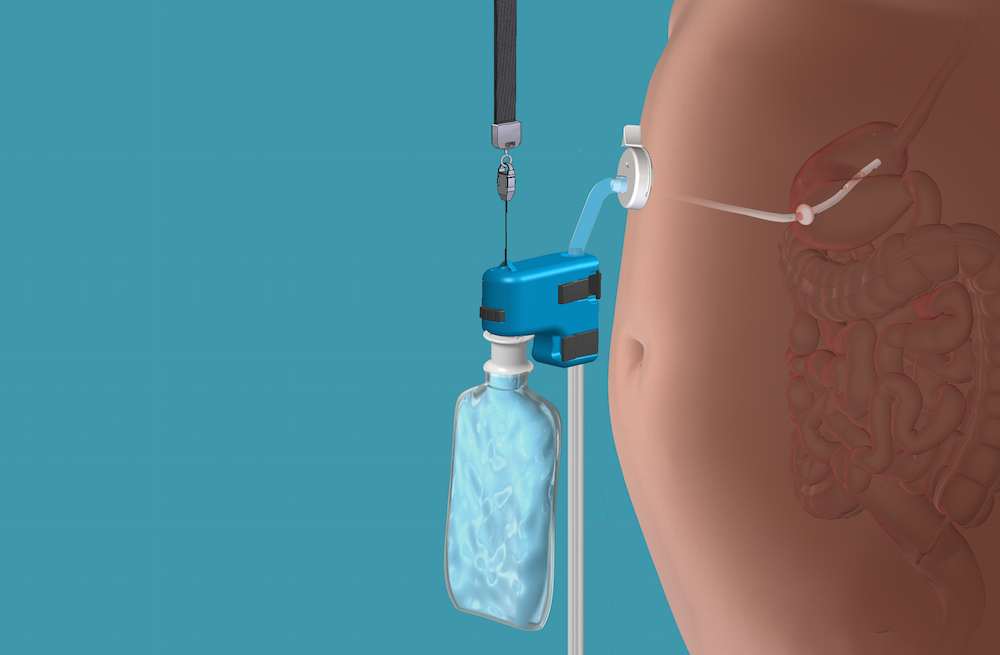

Once the tube is put in place, the patient will need to wait about two weeks for some swelling to go down, Sullivan said. After that, doctors attach a valve to the tube on the outside of the person's abdomen. To drain food from the stomach, patients attach a smartphone-size device to the valve and empty the contents into a toilet in a process called "aspiration." After this first "drain," the person will squeeze a water-filled reservoir attached to the device to flush the stomach before draining the contents again, according to the FDA. The researchers estimated that the patients removed about 30 percent of the contents of the stomach each time they used the system, Sullivan said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But using the device is not as simple as eating and then emptying out your food. Rather, patients need to change their eating habits, Sullivan said.

The inside of the tube is about 0.3 inches (7 millimeters) in diameter, so in order for food particles to fit through the device they need to be smaller than that — about 0.2 in. (5 mm), Sullivan said. That's much smaller than a dime, which is about 0.7 in. (18 mm) across.

That means that patients need to chew their food up really well, until it basically disintegrates in their mouth, Sullivan said. Otherwise, the food particles will get stuck in the tube, and nothing will come out, she said. A clogged tube won't cause any pain, and patients can normally clean it out on their own, though as a last resort doctors can clean the tube using a brush, she said. Getting the tube clogged will probably happen a couple of times as patients are learning how to eat with the device, she added.

Spending so much time chewing up their food means patients eat their meals at a much slower rate than if they were chewing normally, Sullivan said. This goes hand-in-hand with common advice for weight loss: to slow down the rate of eating and be mindful, Sullivan said. When a person eats more slowly, he or she will recognize the feeling of fullness before eating too much, she said. [The Science of Weight Loss: Everything You Need to Know]

In many cases, people equipped with the device end up pushing their plate away before finishing the whole meal because they feel full and are tired of chewing, she said.

After chewing up their food, the patients then need to wait between 20 and 30 minutes before they can use the device to remove the food.

Emptying out the food right after a meal would not work, Sullivan said. Despite all that chewing, food particles still need to broken down even further by the stomach, she said. And by the time food particles are small enough to come out, some of the food has already moved out of the stomach and into the small intestine, she said. Because of this, a person can't empty the entire contents of his or her stomach, she said. Rather, the studies on the device suggest that a person removes, on average, about 30 percent of the calories from a meal, she said. [11 Surprising Facts About the Digestive System]

Sullivan also noted that if a person ate a very large meal, the device would not work. There needs to be space in the stomach for food to flow out through the device, she said.

A license to eat anything?

Although no foods are off-limits to patients using the device, one thing the patients noticed is that when they ate unhealthy food, it looked really gross when it drained out of the tubing, Sullivan said.

"The tube is clear so you can see" what comes out, she said. When a person eats fatty food, the fat separates out, and fatty globs are intermixed with the rest of the food coming out; the result does not look appetizing, she said. Healthier foods, on the hand, looked similar coming out as they do going in — just more chewed up, she said.

In this way, looking at the foods on their way out acted as positive reinforcement for healthier foods and negative reinforcement for unhealthier foods, she said. This added to the drive for patients to change their eating habits.

Indeed, the researchers estimated that the patients removed approximately 30 percent of their calories from a meal, however, this didn't account for all of the weight the patients lost, Sullivan said. Some of that weight loss came from changes in eating habits, she said.

In fact, if people did not change their eating habits, it's very clear that they would not lose any weight, in part because the food would not fit into the tube, Sullivan said. The device will work for weight loss, but it still requires a lot of work on the patient's part, she said.

More research is needed

Not everyone agrees that there's enough research to back up the claims that the device both works to help people lose weight and that it's safe for long-term use.

Aside from how the device might seem from an aesthetic sense, "there's the question of what data do we have that this works?" said Dr. Pieter Cohen, an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a general internist at Cambridge Health Alliance. "I would argue that we have very little to none."

About 200 people participated in the only two studies conducted on the device, Cohen said. (In addition to the year-long trial with 171 people, a smaller study was also included in the FDA's assessment.)

The researchers, however, didn't use a placebo in the study, Cohen said. Without this "control" group, it's unclear whether the people in the study lost weight because they aspirated it from their stomachs, or there was another factor, he said.

There are many psychological and practical factors that would come into play when using a device like this one, Cohen told Live Science. It's possible that people lost the weight because they were told they had a box connected to their stomachs and they needed to remove a third of their food, he said. Or the chewing requirements for the device may have influenced weight loss, he said.

"My guess is that if people had a [placebo] device attached to their stomach that appeared to remove food," there wouldn't be any difference in weight loss compared with people who had the real device in place, he said.

Cohen noted that the FDA requirements to approve a medical device are less stringent than those needed to approve a medication. In other words, more studies would be necessary if a company wanted to approve a new medication, including placebo-controlled studies.

In addition, the long-term benefits of the device are unclear.

Bariatric surgery, for example, doesn't only lead to weight loss, Cohen said. It also changes levels of hormones in the body that influence hunger and has been shown to help reverse Type 2 diabetes, he said. For a device such as AspireAssist, which demands a lot of a person, you would want similarly robust results, he said. [Infographic: Types of Weight Loss Surgery]

Still, Cohen said he is not opposed to exploring this type of approach to weight loss. If there were robust outcomes and it was demonstrably safe, "I'd talk to patients about it as an option" for weight loss, he said. At this point, however, "I think it should be more in the experimental phase," he said.

"We're getting head of ourselves to be recommending this to patients outside of clinical studies," he added.

Originally published on Live Science.