11 Surprising Facts About the Digestive System

Introduction

The digestive system has two main functions: to convert food into nutrients your body needs, and to rid the body of waste. To do its job, the system requires the cooperation of a number of different organs throughout the body, including the mouth, stomach, intestines, liver and gallbladder.

Here are 11 facts about the digestive system that may surprise you.

Food doesn't need gravity to get to your stomach.

When you eat something, the food doesn't simply fall through your esophagus and into your stomach. The muscles in your esophagus constrict and relax in a wavelike manner called peristalsis, pushing the food down through the small canal and into the stomach.

Because of peristalsis, even if you were to eat while hanging upside down, the food would still be able to get to your stomach.

Laundry detergents take cues from the digestive system.

Laundry detergents often contain several different classes of enzymes, including proteases, amylases and lipases. The human digestive system also contains such enzymes.

The digestive system also employs these types of enzymes to break down food. Proteases break down proteins, amylases break down carbohydrates and lipases break down fats. For example, your saliva contains both amylases and lipases, and your stomach and small intestine use proteases.

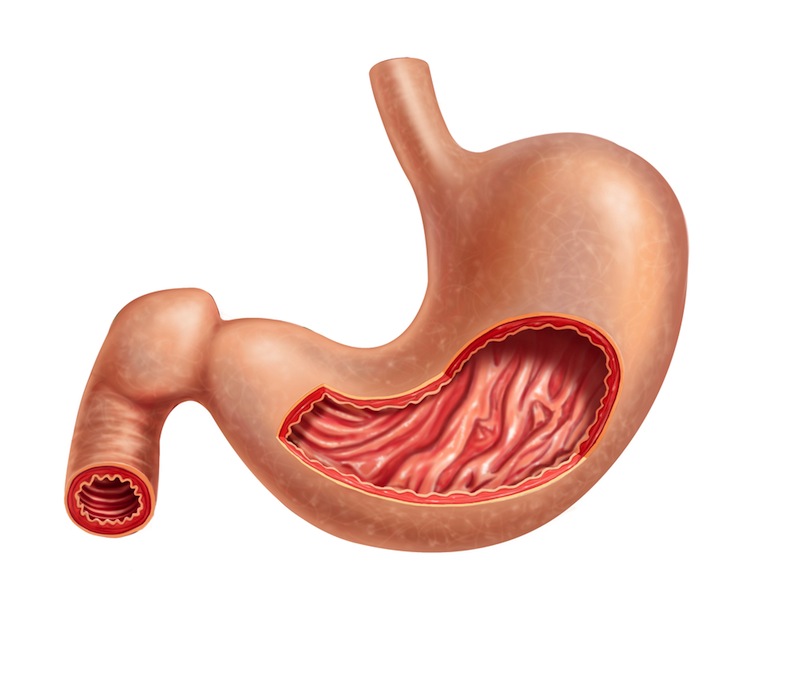

Your stomach doesn't do most of the digestion.

p> It's commonly believed that the stomach is the center of digestion, and the organ does play a large role in "mechanical digestion" — it churns food, and mixes it with gastric juices, physically breaking up food bits and turning them into a thick paste called chyme.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the stomach is actually involved in very little chemical digestion, the process that reduces food to the size of molecules, which is necessary for nutrients to be taken up into the bloodstream.

Instead, the small intestine, which makes up about two-thirds of the length of the digestive tract, is where most of the digestion and absorption of nutrients takes place. After further breaking down the chyme with powerful enzymes, the small intestine absorbs the nutrients and passes them into the bloodstream.

The surface area of the small intestine is huge.

The small intestine is about 22 feet (7 meters) long, and about an inch (2.5 centimeters) in diameter. Based on these measurements, you'd expect the surface area of the small intestine to be about 6 square feet (0.6 square m) — but it's actually around 2,700 square feet (250 square m), or about the size of a tennis court.

That's because the small intestine has three features that increase its surface area. The walls of the intestine have folds, and also contain structures called villi, which are fingerlike projections of absorptive tissue. What's more, the villi are covered with microscopic projections called microvilli.

All of these features help the small intestine to better absorb food.

Stomachs vary in the animal kingdom.

The stomach is an integral part of the digestive system, but it's not the same in all animals. Some animals have stomachs with multiple compartments. (They're often mistakenly said to have multiple stomachs.) Cows and other "ruminants" — including giraffes, deer and cattle — have four-chambered stomachs, which help them digest their plant-based food.

But some animals — including seahorses, lungfishes and platypuses — have no stomach. Their food goes from the esophagus straight to the intestines.

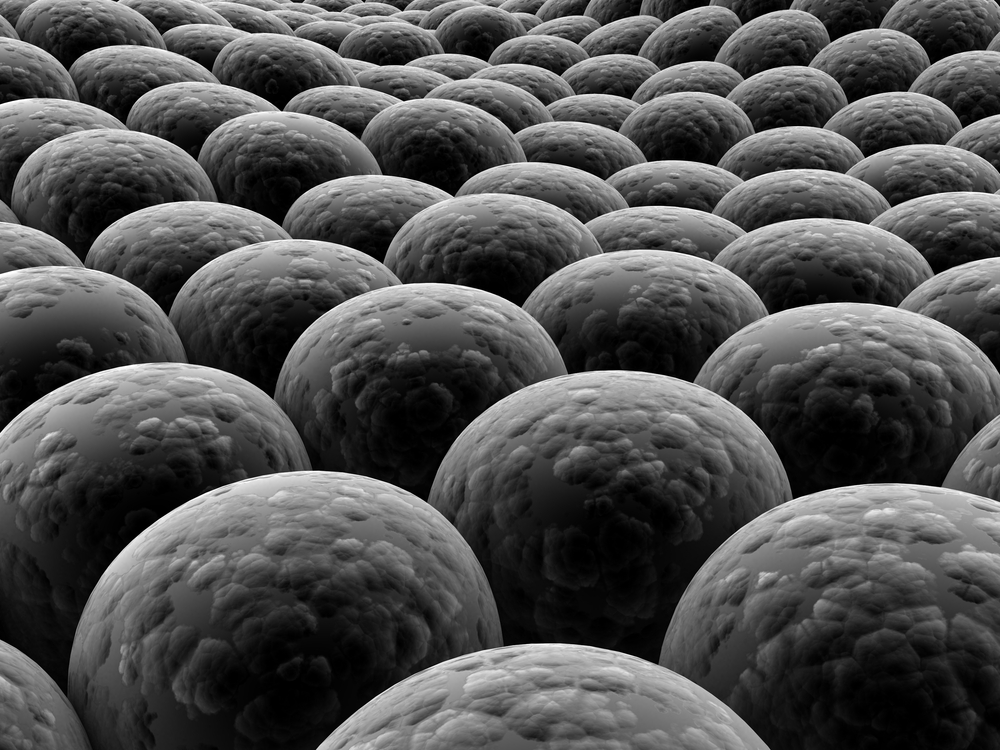

Flatulence gets its smell from bacteria.

p> Intestinal gas, or flatus, is a combination of swallowed air and the gasses produced by the fermentation of bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract. The digestive system cannot break down or absorb certain components of foods, and those substances simply get pushed along the tract, and make their way into the large intestine. Hordes of intestinal bacteria get to work, releasing a variety of gases in the process, including carbon dioxide, hydrogen, methane and hydrogen sulfide (which gives flatulence its rotten-egg stench).

The digestive system is cancer prone.

Each year, more than 270,000 Americans develop a cancer of the gastrointestinal tract, including cancers of the esophagus, stomach, colon and rectum. About half of these cancers result in death. In 2009, colorectal cancer killed almost 52,000 people in the U.S., more than any other cancer except lung cancer.

What's more, the digestive system is home to more cancers, and causes more cancer mortalities, than any other organ system in the body.

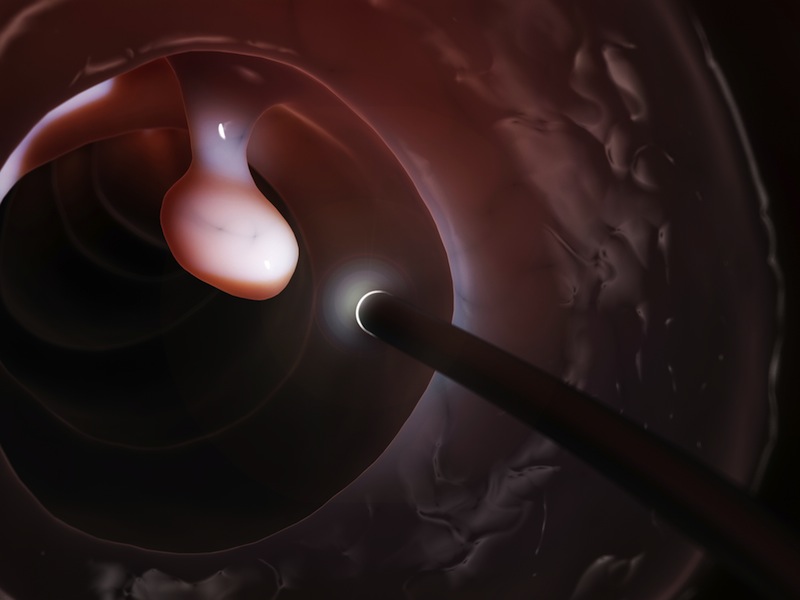

A sword swallower helped doctors look inside the stomach.

An endoscope is an instrument used to examine organs and cavities inside the body. The German physician Philipp Bozzini developed a primitive version of the endoscope, called the lichtleiter (meaning "light conductor"), in the early 1800s to inspect a number of bodily areas, including the ear, nasal cavity and urethra.

Half a century later, French surgeon Antoine Jean Desormeaux developed another instrument, which he named the "endoscope," to examine the urinary tract and bladder.

In 1868, German doctor Adolph Kussmaul used an endoscope to look inside the stomach of a living person for the first time. Unlike today's endoscopes, Kussmaul's instrument was not flexible, making it difficult to guide the instrument deep into the body. So Kussmaul employed the talents of a sword swallower, who could easily gulp down the 18.5-inch by 0.5-inch (47 cm by 1.3 cm) instrument that Kussmaul designed.

A man with a hole in his stomach provided a window into digestion.

In 1822, a fur trapper accidentally shot a 19-year-old man named Alexis St. Martin. Army surgeon William Beaumont successfully patched up St. Martin, but the trapper was left with a hole in his stomach's abdominal wall, which is called a fistula. The fistula allowed Beaumont to investigate the workings of the stomach in entirely new ways.

Over the next decade, Beaumont conducted 238 experiments on St. Martin, some of which involved sticking food directly into his patient's stomach. He drew a number of important inferences from his work, including that fever can affect digestion, and that digestion was more than just a grinding motion of the stomach but also required hydrochloric acid.

The stomach must protect itself — from itself.

Cells along the inner wall of the stomach secrete roughly 2 liters (0.5 gallons) of hydrochloric acid each day, which helps kill bacteria and aids in digestion. If hydrochloric acid sounds familiar to you, it may be because the powerful chemical is commonly used to remove rust and scale from steel sheets and coils, and is also found in some cleaning supplies, including toilet-bowl cleaners.

To protect itself from the corrosive acid, the stomach lining has a thick coating of mucus. But this mucus can't buffer the digestive juices indefinitely, so the stomach produces a new coat of mucus every two weeks.