New Superbug's Genetic Trick Could Help It Spread

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

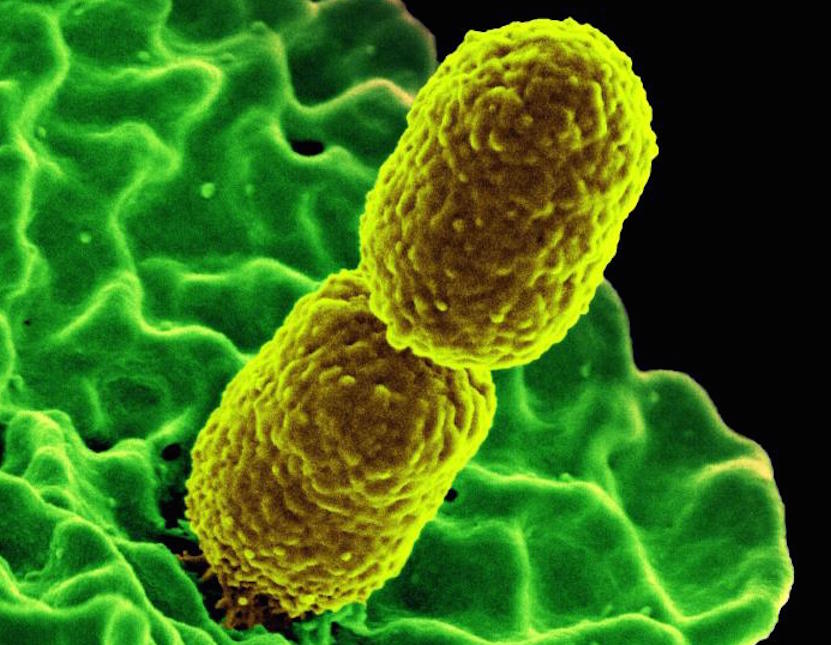

Health experts are keeping a close eye on a type of antibiotic-resistant bacteria called CRE that, while still rare, has the potential to become more widespread in the United States. This type of bug includes some strains of Escherichia coli and other bacteria.

A new report released on Thursday said that in the past five years, researchers have identified 43 patients in the United States who became sick with infections from one type of CRE. (The name is an abbreviation for "carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae," meaning the bacteria are part of a group called Enterobacteriaceae and are resistant to treatment with antibiotics called carbapenems.)

These cases all involved CRE that share a particular method of defeating the antibiotics: they have enzymes called OXA-48-like carbapenemases that break down the drugs, said the report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Other types of CRE have different methods of resisting the antibiotic. [6 Superbugs to Watch Out For]

This particular type of CRE that is the focus of the new report is "noteworthy" because the enzyme that thwarts the antibiotic is encoded on a piece of genetic material called a plasmid, "which can actually move from one bacteria to another," said Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist and professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, who was not involved with the CDC report.

At the moment, this whole group of CRE bacteria is of great interest to researchers, Schaffner told Live Science.

Recently, for example, researchers discovered bacteria in China whose plasmids give them resistance to an antibiotic called colistin, he said. Some doctors consider colistin one of the last lines of defense against certain "superbugs."

The bacteria found in China and the ones in the new report — which both have key resistance genes contained on plasmids — "are of greatest public health concern because of their potential for rapid global dissemination," the researchers wrote in the new report.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Still, Schaffner stressed that, at the moment, these infections are not something the general public needs to worry about. But microbiologists, public health officials and infectious disease specialists are paying attention, he said.

Researchers have seen a few small clusters of cases around the country, which indicate that the infection likely spread in a hospital, Schaffner said.

In the new report, the CDC researchers noted that many of the patients with this particular type of infection had recently traveled out of the country, with India being the most frequent travel destination. In addition, among the patients who reported traveling abroad, 16 had been hospitalized outside of the United States, the report said, suggesting that foreign hospitals are a potential source of some infections.

The CDC is also tracking infections that come from other types of CRE. For example, there have been 118 cases in the United States of infections involving a certain enzyme, different from the one found in the bacteria that are the focus of Thursday's report, the CDC said.

Carbapenems are not considered the last line of defense against Enterobacteriaceae infections, meaning that if these drugs don't work, there are still other antibiotics available. However, the emerging resistance is still concerning to experts. This resistance reduces the number of antibiotics that doctors can use to treat these infections, Schaffner said. Doctors need multiple antibiotics available, and the more options there are, the better, he said.

To reduce the problems associated with antibiotic resistance, doctors and patients need to join together to be more prudent about using antibiotics, Schaffner said.

Follow Sara G. Miller on Twitter @SaraGMiller. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus