CRE Infection: Causes, Symptoms & Treatment

CRE, which stands for carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae, are strains of bacteria that are resistant to carbapenem, a class of antibiotics typically used as a last resort for treating severe infections when other antibiotics have failed. These organisms have been described as "nightmare bacteria" because they have become resistant to nearly all available antibiotics, making CRE infections extremely difficult to treat and potentially deadly.

CRE infections are on the rise in the United States, especially among patients in hospitals, nursing homes and other medical facilities, but they are still a relatively rare occurrence. Even so, in its latest report on the top 18 antibiotic-resistant threats, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has categorized CRE as an "urgent" public-health threat in the United States, which is its highest level of concern.

About 9,300 health-care associated infections in the United States are caused by CRE each year, and almost 50 percent of hospital patients who develop bloodstream infections from CRE bacteria die from them, according to the CDC.

CRE infections are also a serious threat globally, and they have been designated as a critical-priority pathogen by the World Health Organization, meaning they pose the greatest threat to human health.

Causes

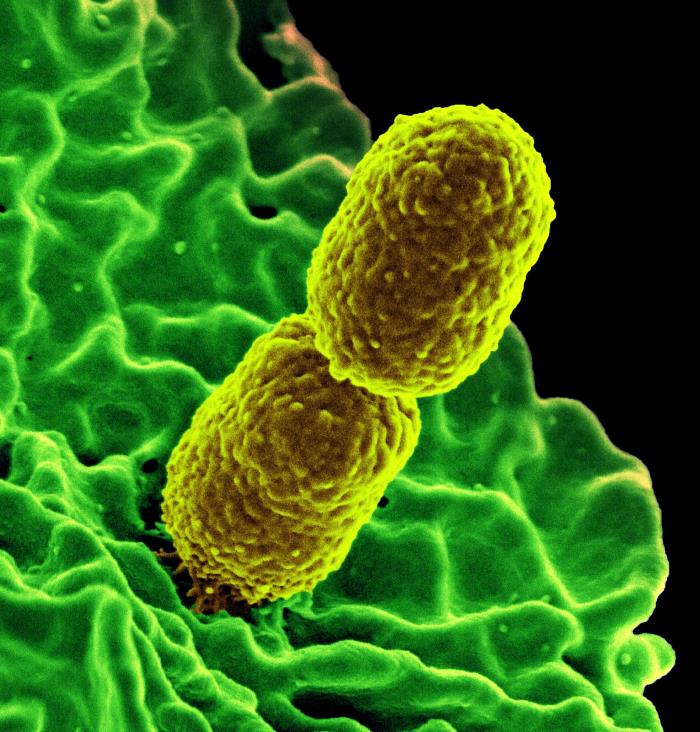

Enterobacteriaceae are a family of bacteria that include Klebsiella and E. coli, which are normally found in people's digestive tract, where they are usually harmless. But if these bacteria spread outside of the intestines into other areas of the body where they don't belong, such as the bloodstream, bladder, lungs or skin, they can cause bacterial infections, according to the CDC.

A class of broad-spectrum antibiotics called carbapenem may be used as a last resort to kill Enterobacteriaceae. But when antibiotics are overused, some Enterobacteriaceae bacteria have become resistant to most available antibiotics, resulting in CRE, according to the North Dakota Department of Health. Some types of CRE can produce enzymes called carbapenemases that can break apart carbapenem antibiotics and make them ineffective, according to the Minnesota Department of Health.

CRE are essentially "normal" bacteria that have acquired the ability to produce enzymes that work against most antibiotics, making these powerful drugs ineffective when fighting infections and no longer capable of killing the bacteria. These "superbugs" can spread and share their antibiotic-resistant qualities with healthy bacteria in the body, leading to hard-to-treat infections, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Risk factors for infection

CRE infections are likely transmitted when health-care professionals have direct contact with an infected person's bodily fluids, such as blood, drainage from a wound, urine, stool or phlegm, according to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. For example, a nurse may touch the wound of an infected patient, and then touch another patient, infecting the second patient with the bacteria.

The infections can also spread by touching medical equipment or a contaminated surface that has come in contact with the bacteria, such as a bed rail. It is not known how long the bacteria can remain alive on contaminated surfaces, according to the West Virginia Bureau of Health.

Healthy people generally are not at risk of becoming infected with CRE. The people most likely to get the infection are those with weakened immune systems who stay in health-care facilities. CRE also affects people who use urinary catheters (a tube in their bladder), intravenous catheters (in a vein) or ventilators (breathing machines), and those taking long-courses of certain antibiotics, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Most of the people who pick up CRE infections are patients in hospitals, nursing homes, and other types of health-care facilities, said John R. Palisano, a professor of biology at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee. "They are exposed to carbapenem-resistant bacteria while they are on ventilators or after undergoing medical procedures involving catheters or endoscopes (a flexible tube that allows doctors to view the digestive tract), with medical instruments that were not properly cleaned and sterilized."

Symptoms

CRE can cause a variety of illnesses, depending on where the bacteria spread. These may include blood infections, wound infections, urinary tract infections and pneumonia, according to the CDC.

As a result, the symptoms of CRE can be different for each patient. "The symptoms of infection can vary depending on the organs (like the lungs or bladder) that are involved, but they usually include a high fever and chills," Palisano told Live Science.

Most CRE infections occur in health-care settings, said Mary B. Farone, a professor of biology at Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro. For caregivers in these facilities, they should look for fever and drowsiness in patients, Farone said. It is also important to monitor any areas of swelling, redness or soreness — under the skin, not necessarily open sores — that persist, she added.

Diagnosis

A blood culture is typically done to diagnose the infection. For this test, a sample will be taken from a person's blood and sent to a lab, according to the U.S. National Library of Medicine. The cells in the blood sample will be placed in a special dish called a culture and watched to see if any disease-causing bacteria grow and can be identified. (Cultures can also be done using samples from the urine, skin, or lungs, depending on where the infection is located.) Once the specific bacteria are identified, your doctor can then determine which antibiotics, if any, may be effective for treating the infection.

CRE are a type of bacteria called gram-negative, making them easy to identify from lab cultures. "Bacteria are categorized as either gram-negative or gram-positive, based on how they react with certain dyes for diagnostic purposes," said Shahriar Mobashery, a life sciences professor at the University of Notre Dame. "Members of both groups could be antibiotic resistant, and they are problematic in their own ways," he said.

Treatment

Treatment options for CRE infections are extremely limited: There are only a few antibiotics that may treat CRE, which is why the mortality rate for the infection is so high. Bacterial strains of CRE that are resistant to all antibiotics are very rare but have been reported, according to the CDC.

Antibiotics that are currently used to treat CRE are polymyxins, aminoglycosides and fosfomycin, according to a 2015 review in Open Forum Infectious Diseases. But the review also said that these drugs have been rarely used due to concerns about their effectiveness and toxicity. Sometimes combinations of drugs have been used for treating severe CRE infections, which may decrease mortality rates, compared with using a single drug.

Some newer treatments have been developed to fight CRE. In February 2015, the FDA approved the use of a new antibiotic combination known as Avycaz (ceftazidime-avibactam) for the treatment of complicated urinary tract infections and complicated intra-abdominal infections. The drug has also been approved for use with hospital-acquired or ventilator-assisted bacterial pneumonia, according to Medscape.

In August 2017, the FDA approved a new antibiotic combination drug for the treatment of complicated urinary tract infections caused by CRE. The drug, known as Vabomere, is a combination of meropenem and vaborbactam, and is said to work by inhibiting the production of enzymes that block the effectiveness of carbapenem antibiotics, according to the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy.

Once a person has been infected with CRE, he or she can become infected again and is not immune to future CRE infections, according to the North Dakota Department of Health.

Prevention

Prevention can minimize the spread of CRE. Cleanliness is a key part of preventing the transmission of the bacteria in a health-care facility. Palisano said that medical devices should be scrupulously cleaned and sterilized before use. Once cleaned and sterilized, devices should be handled only by properly trained personnel to maintain a clean and sterile workspace. At home, frequent hand washing and sanitization of surfaces can help to prevent the spread of CRE by caregivers and people with the infection.

The use of antibiotics should also be limited. "Antibiotics should be carefully used only under conditions that warrant their use and should always be used as prescribed," Palisano said.

Farone agreed and told Live Science that the best way to prevent the emergence of such deadly bacteria is to follow a physician's instructions when taking medication, especially antibiotics. "If you do not understand the proper way to take your antibiotics or why you need to completely finish a prescription, ask your pharmacist or health care provider," Farone said.

Additional reporting by Cari Nierenberg, Live Science contributor.

Additional resources

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus