'Nightmare Bacteria' Require Old and New Weapons

"Superbug" bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics have the potential to create a nightmare scenario for modern medicine, but experts are hopeful that doctors will be able to slow the spread of these scary infections, by both traditional means and new innovations.

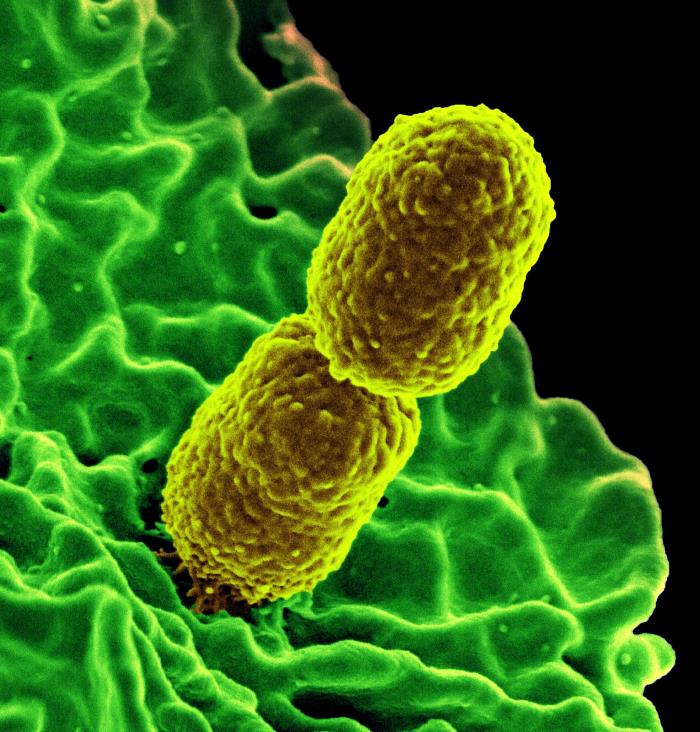

Recently, a Los Angeles hospital announced that more than 100 patients treated there had potentially been exposed to CRE, or carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae, bacteria that are resistant to many antibiotics. The bacteria appear to have contaminated a piece of medical equipment used at the facility called an endoscope, which is a flexible tube that doctors use to view the digestive tract. Seven patients at the hospital were infected with CRE after they underwent an endoscopy with the device.

Endoscopies are generally considered to be low-risk procedures, but two of the patients died from their infections, the hospital said.

As antibiotic-resistant bacteria like CRE become more common, they threaten the safety of modern medicine, because they can make routine procedures more risky, experts told Live Science.

"Lots of procedures that go on in hospitals ... are made safer because we use antibiotics," said Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease specialist and a senior associate at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center's Center for Health Security. "If antibiotic resistance continues to increase, all of the stuff that’s part of modern medicine and done routinely will become more dangerous," Adalja said.

CRE have been dubbed "nightmare" bacteria, because they are resistant to nearly all antibiotics, and they can be highly lethal, killing up to 50 percent of infected patients, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

CRE infections first appeared in the United States only in 2001, and have increased in recent years. A CDC study found that in 2012, nearly 5 percent of U.S. hospitals, and 18 percent of long-term care facilities reported having at least one patient with CRE. [6 Superbugs to Watch Out For]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To reduce the spread of CRE and other superbugs, it's important for doctors to change how they use antibiotics, and for researchers to come up with new alternatives to fight these infections, experts said.

'Nightmare' bacteria

CRE are essentially "normal" bacteria that have acquired the ability to produce enzymes that work against most antibiotics. These CRE enzymes can even counter antibiotics that doctors generally use as a "last resort" to treat bacterial infections. "Our toolbox against CRE is very small," Adalja said.

Bacteria naturally produce such enzymes as a defense against other bacteria. Scientists have found genes that confer resistance to antibiotics even in environments were there have never been any humans, said Dr. Jesse Goodman, director of Georgetown University's Center on Medical Product Access, Safety and Stewardship. When doctors use antibiotics frequently, it spurs bacteria to activate these defenses, and develop resistance.

"These genes are out there in nature, but it's our use of antibiotics that makes them become more selected for, and much more widespread," Goodman said.

Right now, CRE infections typically occur in people who need long-term care, require treatment with medical equipment such as ventilators or catheters, or are put on long courses of antibiotics. Doctors don't know all the ways that CRE is spread, but the bacteria appears to be transmitted by health care workers — for example, if they have contaminated hands or clothing — and by medical devices.

CRE infections are still relatively uncommon in the United States; a study published last year in the journal Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology found that, among 25 hospitals in the Southeast, there were about 300 cases of CRE infections over a five-year period.

But the concern is that infections will increase. The recent outbreak in Los Angeles "illustrates what can happen when CRE becomes more common in the health care environment," Goodman said.

Doctors may also run out of antibiotics that they can give patients prophylactically, meaning as a protective measure before surgery or other invasive medical procedures that come with a risk of infection, Adalja said.

"The risk-benefit calculation [of many medical procedures] could be altered if the rise in antibiotic resistance continues," Adalja said.

Preventing infections

One important step to reducing CRE infections is to limit the use of powerful antibiotics to when they're really needed, Goodman said. Studies have found that all too often, patients are given antibiotics when they don't need them (such as when they have a cold or other infection caused by a virus), or are kept on antibiotics for too long.

For bacteria, it is costly to carry around genes for resistance against certain antibiotics unless this defense is really needed, Goodman said. So "if you can reduce people's exposures [to antibiotics], where they're unnecessary, you can at least slow this down," Goodman said.

Adalja agreed, and said that alternatives to antibiotics are also needed, because in an "arms race with bacteria, there's no question that we will lose."

One important area of research that could help prevent antibiotic-resistant infections is the study of the microbiome, or the diverse community of microorganisms that naturally live on and in people's bodies and promote health, Goodman said. Studies have shown that when a person's normal gut bacteria community is disturbed, it puts that individual at risk for becoming sick with "bad" bacteria, including CRE. Research that looks into how to prevent the normal microbiome from being disturbed, or how to restore the normal microbiome after illness or antibiotics, could help treat or prevent infections, Goodman said.

New vaccines against bacterial diseases could also help protect people against certain infections that often develop in health care settings, Goodman said.

And traditional practices to prevent infections — such as consistent hand washing, and the proper use of personal protective equipment — are essential. Studies have found that hospitals can dramatically reduce CRE infections when they implement proper use of these practices, Goodman said

"I definitely think that it's achievable to slow the spread of these infections," Goodman said. Increasing antibiotic resistance "is a nightmare scenario, but there's a lot we can do."

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.