Scientists Finally Figure Out How Bees Fly

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Proponents of intelligent design, which holds that a supreme being rather than evolution is responsible for life's complexities, have long criticized science for not being able to explain some natural phenomena, such as how bees fly.

Now scientists have put this perplexing mystery to rest.

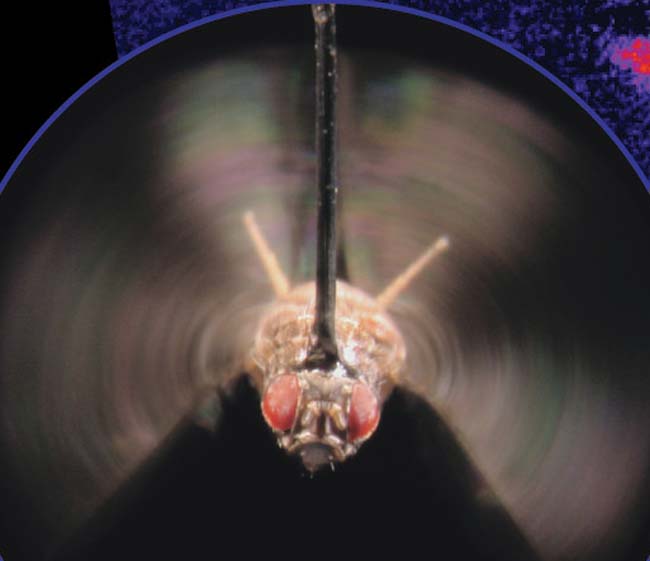

Using a combination of high-speed digital photography and a robotic model of a bee wing, the researchers figured out the flight mechanisms of honeybees.

"For many years, people tried to understand animal flight using the aerodynamics of airplanes and helicopters," said Douglas Altshuler, a researcher at California Institute of Technology. "In the last 10 years, flight biologists have gained a remarkable amount of understanding by shifting to experiments with robots that are capable of flapping wings with the same freedom as the animals."

Exotic flight

The scientists analyzed pictures from hours of filming bees and mimicked the movements using robots with sensors for measuring forces.

A movie of a bee in flight was filmed at 6,000 frames per second by Douglas Altshuler and Jason Vance.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Turns out bee flight mechanisms are more exotic than thought.

"The honeybees have a rapid wing beat," Altshuler told LiveScience. "In contrast to the fruit fly that has one eightieth the body size and flaps its wings 200 times each second, the much larger honeybee flaps its wings 230 times every second."

This was a surprise because as insects get smaller, their aerodynamic performance decreases and to compensate, they tend to flap their wings faster.

"And this was just for hovering," Altshuler said of the bees. "They also have to transfer pollen and nectar and carry large loads, sometimes as much as their body mass, for the rest of the colony."

Try this!

In order to understand how bees carry such heavy cargo, the researchers forced the bees to fly in a small chamber filled with a mixture of oxygen and helium that is less dense than regular air. This required the bees to work harder to stay aloft and gave the scientists a chance to observe their compensation mechanisms for the additional toil.

The bees made up for the extra work by stretching out their wing stroke amplitude but did not adjust wingbeat frequency.

"They work like racing cars," Altshuler said. "Racing cars can reach higher revolutions per minute but enable the driver to go faster in higher gear. But like honeybees, they are inefficient."

The work, supervised by Caltech's Michael Dickinson, was reported last month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The scientists said the findings could lead to a model for designing aircraft that could hover in place and carry loads for many purposes such as diaster surveillance after earthquakes and tsunamis. They are also pleased that a simple thing like bee flight can no longer be used as an example of science failing to explain a common phenomenon.

Proponents of intelligent design, or ID, have tried in recent years to promote the idea of a supreme being by discounting science because it can't explain everything in nature.

"People in the ID community have said that we don't even know how bees fly," Altshuler said. "We were finally able to put this one to rest. We do have the tools to understand bee flight and we can use science to understand the world around us."

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus