'Bizarre,' Human-Size Sea Scorpion Found in Ancient Meteorite Crater

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

About 460 million years ago, a sea scorpion about the size of an adult human swam around in the prehistoric waters that covered modern-day Iowa, likely dining on bivalves and squishy eel-like creatures, a new study finds.

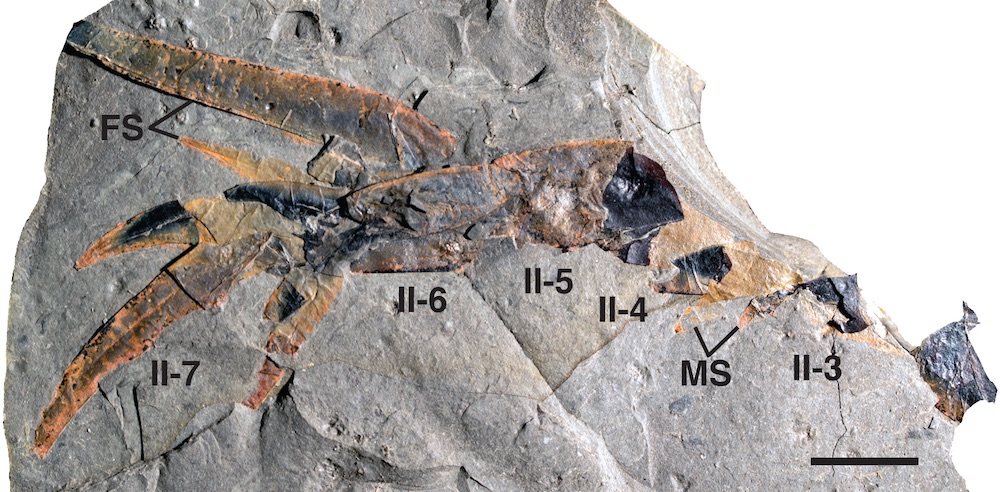

The ancient sea scorpions are eurypterids, a type of arthropod that is closely related to modern arachnids and horseshoe crabs. The findings — which include at least 20 specimens — are the oldest eurypterid fossils on record by about 9 million years, said study lead researcher James Lamsdell, a postdoctoral associate of paleontology at Yale University.

The findings are also the largest known eurypterids from the Ordovician period, which began approximately 488 million years ago and ended 443.7 million years ago. The sea creatures measured up to 5.6 feet (1.7 meters) long. [See Images of the Ancient Sea Scorpion]

Researchers dubbed the newfound species Pentecopterus decorahensis, named for Greek warships (penteconter) and the Greek word for wings (pterus) because the sea scorpion was likely a top predator that sped through the water, the researchers said. The species name also honors the Iowa city of Decorah, where the fossils were uncovered.

"The best way to describe this animal is bizarre," Lamsdell told Live Science. "For a long time, I had trouble being sure that this was one species because there are so many strange things about it."

Paddle-shaped limbs

An analysis showed that P. decorahensis had specialized limbs that developed as it aged. Its rear limbs are shaped like paddles with joints that appear to be locked in, suggesting that the predator used them as paddles to swim or dig, the researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Its second and third pairs of limbs were likely angled forward, which suggests they helped the ancient arthropod grab prey. Moreover, the three back pairs of limbs are shorter than the front pair, indicating that P. decorahensis walked on six legs instead of eight.

Interestingly, juveniles had different spines on their legs than adults did.

"It looks like the juveniles would have behaved more like horseshoe crabs, sort of walked around on the seafloor, grubbing in the mud, just eating worms or whatever they could find," Lamsdell said.

With age, their back legs shrank and probably helped the eurypterids balance while swimming. The front legs grew, as did the sharp spines growing on them, "and they could have been used for catching larger prey," Lamsdell said.

Like other arthropods, P. decorahensis probably molted as it aged. Researchers speculate that eurypterids molted "en masse, and accumulations of molts have been reported from a number of sheltered, marginal marine environments," the researchers wrote in the study. Perhaps the specimens found in Iowa are molted skin, they said. [Skin Shedders: A Gallery of Creatures That Molt]

Even so, the fossils provide exquisite detail, showing scales, follicles and stiff bristles that once covered the animals. For instance, its rear limbs are covered with dense bristles. Horseshoe crabs have similar bristles that expand the surface area of its paddles as it swims, but P. decorahensis' smaller bristles suggest they may have been sensory in nature, the researchers said.

Meteorite pockmark

Workers with the Iowa Geological Survey uncovered the fossils in the Upper Iowa River during a mapping survey.

The fossils were found at the bottom of a meteorite impact crater, a scar left from when Earth was battered about 470 million years ago, Lamsdell said. The so-called Ordovician meteor event left a "series of pockmarks" across the United States, and predated the newfound eurypterid fossils by several million years, he added.

Researchers found more than 150 fossil fragments from the site — an 88.5-foot-thick (27 m) formation in northeastern Iowa known as Winneshiek Shale. The fossils are also well preserved, and can be peeled off the rock and studied under a microscope.

"It really looks like an animal that has just shed its skin," Lamsdell said. "I've never seen anything like this before."

The new study is "exciting material," said Roy Plotnick, a professor of paleontology at the University of Illinois at Chicago, who was not involved in the study.

"To find something as well preserved as this is pretty exciting, especially given that it's old and yet has features of more advanced forms," Plotnick said. "That tells us that somewhere in even older rocks should be even more ancestral forms to find."

The study was published online Monday (Aug. 31) in the journal BMC Evolutionary Biology.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus