Ectopic pregnancy: Signs, symptoms & treatment

Such pregnancies are not viable and can be life-threatening.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

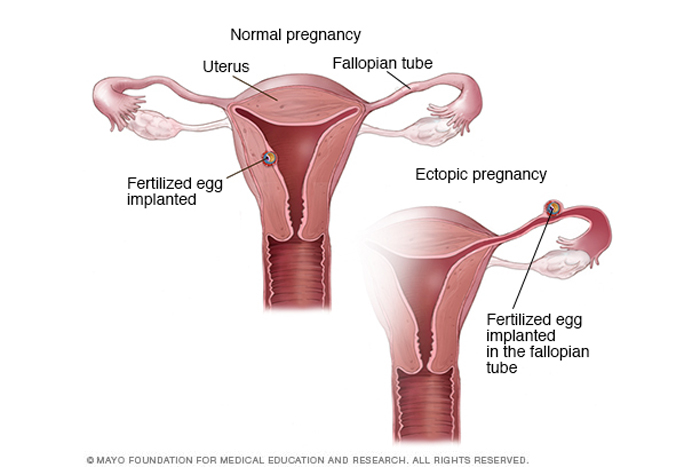

An ectopic pregnancy occurs when a fertilized egg implants outside the uterus or not within the uterine cavity. The word "ectopic" refers to something medically that is in the wrong place or position. Ectopic pregnancies cannot be carried to term, and it is not possible to transplant an ectopic pregnancy to the uterus. Termination of the pregnancy is the only treatment; if not aborted immediately, an ectopic pregnancy can be life-threatening.

In more than 90% of ectopic pregnancies, the fertilized egg implants within a fallopian tube, the narrow tube that links the ovaries and the uterus. This is also called a tubal pregnancy. In rare cases, the fertilized egg can implant in the cervix or in a scar from a previous cesarean section, according to the Mayo Clinic. Rarely, a fertilized egg can attach directly to an ovary, the cervix or an organ in the abdomen, such as the abdominal wall.

Ectopic pregnancies never develop into a full-term fetus. When an embryo implants in a location other than the uterine wall, it cannot develop normally. Locations other than the uterus don't have enough space or the right tissue for the embryo to grow, according to Planned Parenthood.

"The uterus is a unique organ that can stretch dramatically with a growing pregnancy," said Dr. Jennifer Kickham, an obstetrician and gynecologist and the medical director of the outpatient gynecology clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. "No other tissue in the body has the ability to grow to accommodate a nine-pound baby or twins," she told Live Science.

Because of this, an ectopic pregnancy can be dangerous and requires immediate medical attention for its termination. As the embryo grows in an ectopic pregnancy, it can cause the organ it attaches to, such as a fallopian tube or an ovary, to rupture. If this occurs, it can lead to severe internal bleeding and infection. In some cases, this is fatal, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).

Despite the dangers, most people who experience an ectopic pregnancy can be treated and have normal pregnancies in the future, according to Planned Parenthood.

In the United States, 1% to 3% of all pregnancies are ectopic; it is more common than people realize, according to ACOG.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What are the symptoms of an ectopic pregnancy?

Symptoms of an ectopic pregnancy most commonly appear six to 10 weeks after a missed menstrual period. Usually, the most common signs of an ectopic pregnancy are vaginal bleeding and/or pain in the abdomen or pelvis, especially on one side of the body, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Some people may have shoulder pain or lower back pain. There may also be some dizziness or fainting, because of blood loss. Specific symptoms can depend on where blood collects, and some people may have no symptoms at all until a fallopian tube ruptures. When that happens, heavy bleeding in the abdomen can cause lightheadedness, fainting and shock.

What causes an ectopic pregnancy?

Anything that affects the ability of the egg to travel down the fallopian tube into the uterus — such as prior damage to the fallopian tubes, tubal abnormalities or infections that may block the tube — can make an ectopic pregnancy more likely.

The following conditions may increase the risk of an ectopic pregnancy:

- A prior ectopic pregnancy.

- A history of infertility.

- A history of sexually transmitted diseases, such as infections caused by gonorrhea or chlamydia.

- A history of pelvic inflammatory disease, a condition that can damage the fallopian tubes, uterus and other parts of the pelvis.

- A history of endometriosis, a condition in which cells that normally line the uterus implant and grow elsewhere in the body, such as the ovaries or bladder.

- Scars inside the pelvis from a burst appendix or past surgeries.

- Pregnancy while using an intrauterine device (IUD) or after having "tubes tied," which is known as a tubal sterilization or tubal ligation.

- A history of smoking cigarettes.

- A history of multiple sexual partners, as this may increase the risk of pelvic infections.

Ectopic pregnancies are likely caused by a combination of prior medical history and lifestyle factors, and are not caused by genetic factors, Kickham said. However, about half of ectopic pregnancies occur in cases where there are no known risk factors, according to ACOG.

As described above, anything that affects the functioning of the fallopian tubes, such as prior tubal surgeries or pelvic infections, can increase the risk of an ectopic pregnancy, as do factors that can slow movement in the fallopian tube, such as cigarette smoking.

How do doctors diagnose an ectopic pregnancy?

To diagnose an ectopic pregnancy, doctors may administer a blood test to someone who has vaginal bleeding and pelvic pain, to determine levels of a hormone called human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which is present only during pregnancy.

Home pregnancy tests detect hCG in the urine, but if an ectopic pregnancy is suspected, doctors need to measure the levels of hCG in the blood. In a normal pregnancy, hCG levels roughly double in a period of 48 to 72 hours, but levels may rise more slowly in an ectopic pregnancy, Kickham said.

In addition, a person suspected of experiencing an ectopic pregnancy may get a transvaginal ultrasound, in which a wand-like device is inserted into the vagina to examine the reproductive organs, including the uterus, ovaries, cervix and fallopian tubes. Ultrasound uses high-frequency sound waves to create images that can identify whether a pregnancy is located inside or outside the uterus.

Sometimes, a transvaginal ultrasound can reveal if the embryo is growing outside the uterus, though it can't always detect an ectopic pregnancy. But if levels of hCG are between 1,500 and 2,000 mIU/mL and the ultrasound can't detect an intrauterine gestational sac, an ectopic pregnancy is suspected even if the embryo is not directly observed, researchers reported in 2005 in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

An ectopic pregnancy diagnosis can be upsetting, Kickham said. Some patients may ask, "Is it possible to move the pregnancy to the uterus?" she said, but unfortunately, there is no medical technology available to move the pregnancy to the uterine cavity, and abortion is the only treatment.

What are the risks of an ectopic pregnancy?

Ectopic pregnancies are the leading cause of maternal death during the first trimester and account for 10% to 15% of all pregnancy-related deaths, according to a study published in 2013 in the journal International Women's Health.

Although ectopic pregnancies usually are detected in the first trimester, they are sometimes not discovered until the second trimester. However, these instances are extremely rare, and they are also treated by terminating the pregnancy, researchers reported in 2017 in the journal The BMJ.

How are ectopic pregnancies terminated?

If there is no danger that the fallopian tube will rupture, treatment for an ectopic pregnancy typically involves medication — for example, an injection of methotrexate, a drug used in cancer treatment. This medication stops the growth of the embryo, allowing the body to resorb the tissue. A benefit of this treatment is that it does not affect the fallopian tubes, meaning it should not interfere with future pregnancies.

Blood is drawn twice, on the fourth and seventh days after the methotrexate injection, so that doctors can see that levels of hCG have dropped by 15% or more during this time period, Kickham said.

If hCG levels have not been reduced by at least 15%, a second injection of methotrexate is needed to make sure that hCG levels are falling. An ectopic pregnancy ends when hCG levels have dropped to zero.

However, some people may need to undergo a surgical abortion to end the ectopic pregnancy, Kickham said. Surgery may involve removing the entire fallopian tube, for example. This operation can be done laparoscopically, which is a form of minimally invasive surgery that requires a small incision, which is usually done on an outpatient basis and has a shorter recovery time than a more invasive surgical procedure.

In some situations, surgeons may cut a larger incision in the abdomen to end the ectopic pregnancy. Sometimes, the fallopian tube may be removed if it's damaged, and other times, it can be surgically repaired.

During twin pregnancies, it's possible — but rare — for one embryo to implant in the uterus while a second implants at an ectopic location, outside of the uterus. When a woman has a heterotopic pregnancy — in which one twin grows in the uterus and the other twin is an ectopic pregnancy, usually in the fallopian tube — it is too risky to treat the woman with medication. In such cases, surgery is necessary to remove the embryo in the fallopian tube, but the other twin can continue developing in the uterus, Kickham said.

Usually, someone who has had an ectopic pregnancy is encouraged to wait at least three months before attempting to become pregnant again, Kickham said. Because an ectopic pregnancy is a type of early pregnancy loss, it takes time to heal from it, both physically and emotionally.

Additional resources

Learn how to recognize the warning signs of an ectopic pregnancy in a guide from The New York Times. Explore resources for early pregnancy loss at the support group Share Pregnancy and Infant Loss Support Inc. In recent years, some anti-abortion legislation has erroneously referred to ectopic pregnancies as viable, or has sought to prohibit their termination despite the deadly risk that would pose to the mother. One such bill was introduced in Missouri in March 2022 by Missouri State Assembly Rep. Brian Seitz, and another was proposed by the Ohio State House of Representatives in 2019.

This article is for informational purposes only, and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Bibliography

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2018, February). Ectopic pregnancy: Frequently asked questions. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/ectopic-pregnancy

Mayo Clinic. (n.d.). Ectopic pregnancy. Retrieved March 11, 2022, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/ectopic-pregnancy/symptoms-causes/syc-20372088

Planned Parenthood. (n.d.). Ectopic pregnancy. Retrieved March 11, 2022, from https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/pregnancy/ectopic-pregnancy

Murray, H. “Diagnosis and Treatment of Ectopic Pregnancy.” Canadian Medical Association Journal, vol. 173, no. 8, 2005, pp. 905–912., https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050222.

Lawani, Osaheni, et al. “Ectopic Pregnancy: A Life-Threatening Gynecological Emergency.” International Journal of Women's Health, 2013, p. 515., https://doi.org/10.2147/ijwh.s49672.

Tucker, Katherine, et al. “Delayed Diagnosis and Management of Second Trimester Abdominal Pregnancy.” BMJ Case Reports, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2017-221433.

Sneed, Annie. “How to Recognize and Treat an Ectopic Pregnancy.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 17 Apr. 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/article/ectopic-pregnancy-guide.html.

Share Pregnancy & Infant Loss Support, 8 Mar. 2022, https://nationalshare.org/.

House Bill No. 2810, General Assembly of the state of Missouri, https://www.house.mo.gov/billtracking/bills221/hlrbillspdf/5798H.01I.pdf.

“House Bill 413.” House Bill 413 | The Ohio Legislature, https://www.legislature.ohio.gov/legislation/legislation-summary?id=GA133-HB-413.

Originally published on Live Science.

Cari Nierenberg has been writing about health and wellness topics for online news outlets and print publications for more than two decades. Her work has been published by Live Science, The Washington Post, WebMD, Scientific American, among others. She has a Bachelor of Science degree in nutrition from Cornell University and a Master of Science degree in Nutrition and Communication from Boston University.

- Mindy WeisbergerLive Science Contributor

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus