Why Matisse's Vibrant Painting of Nudes Is Fading

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists are peeling back layers of paint to get to the root of an enduring plague that is threatening century-old art by the likes of Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet and Henri Matisse.

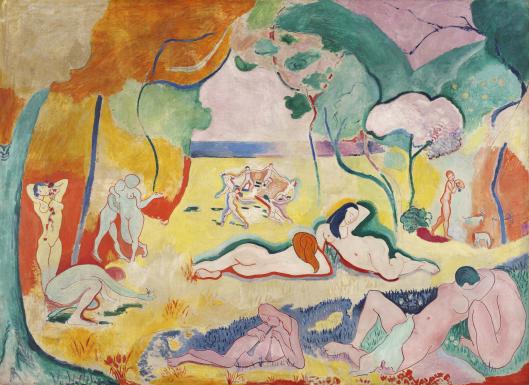

By studying the yellow paint from Matisse's "The Joy of Life" — a vibrantly colored land- and seascape dotted with several nude figures — researchers have found the chemical process that weakens the brilliant sunflowerlike color, called cadmium yellow, to a milky-gray hue in this and other artworks.

"We can finally see across several different countries, across several different artists and several different paintings, we can see the same mechanism going on. And so now we can finally point to: This is the process that's happening and this is what we need to do to stop it," said study co-author Jennifer Mass, a scientist at the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Delaware. "Literally billions of dollars' worth of art is affected by this chemistry." [In Photos: Van Gogh Masterpiece Reveals True Colors]

Cadmium yellow (a cadmium sulfide compound) was prevalent in many paintings between the 1880s and 1920s, so the findings may apply to more than Matisse's piece.

"This is actually a pretty important problem among the whole cast of paintings from the early 1900s," said Robert Opila, a professor of materials science at the University of Delaware, who is not directly involved with the current study. Opila worked with Mass in previous studies on the cadmium yellow pigment in "The Joy of Life."

Pigment breakdown

Between 1905 and 1906, Matisse painted four different copies of the same scene in "The Joy of Life," translated from the original French, "Le Bonheur de Vivre." Two of the copies are at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, one is at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and one is at the Museum of Copenhagen.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The copy at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art maintained the vibrant yellow pigment that fills in the spaces between the reclining nudes in the middle of Matisse's masterpiece. But a copy at the Barnes Foundation is gradually but steadily reacting with light and air and fading to a dull ivory color. [In Photos: Looking for a Hidden Da Vinci Painting]

Researchers took samples from one of the copies at the Barnes Foundation. "If we want to study the full paint layer, we take a scalpel and remove a tiny sample of the painting" that is equivalent to the size of a period at the end of a sentence of a Times Roman 10-point font, Mass said.

The microscopic sample is mounted and cut — researchers look at the cross-section in the same way they would a slice of layered cake. The original bright-yellow color remained at the base of the paint layer, covered by the faded ivory color at the surface.

When that top layer was exposed to air, the water-resistant, bright-yellow cadmium sulfide oxidizes into cadmium sulfate. "What we think is happening is that the sulfide oxidizes to sulfate, then it reacts with the materials from the binder and the varnish," Mass told Live Science. The binder, an oil paint used to make the paint stick to the canvas, can degrade to beige cadmium carbonate and cadmium oxalate.

As for why one copy was not fading, Mass suggests Matisse substituted another pigment rather than cadmium yellow. (Matisse painted the now-faded copy at the Barnes Foundation in Paris, but completed the San Francisco Museum painting in the South of France earlier in the year 1905.)

Without the initial tube of paint that Matisse used, however, the scientists can't determine the initial state of the pigment particles. "We're not sure how much of the cadmium carbonate was there to begin with because we don't have the original pigments," Opila said.

Researchers often try making their own pigment concoction with the chemicals from the early 1900s and then run experiments on them to see how they degrade, Opila said. "But the problem is, they degraded pretty slowly, so the products that we're seeing degrading in 'The Joy of Life' and in 'The Scream' [by Edvard Munch], they've had 100 years to decay," Opila said.

Opila and Mass have the tubes of paint that Munch used for his iconic painting of a horrified scream amid a swirling orange and red sky, and plan to run experiments on the tubes and painting in the near future, Opila said.

Then and now

Today's artists don't have to worry about their yellow paint fading in this way. Paint manufacturers learned a new heating technique at the end of the 1920s to preserve the color of the cadmium yellow compound, past the time Matisse and his contemporaries painted. "So if you went out to the art supply store and you purchased a tube of cadmium yellow now it would be perfectly stable," Mass said. [9 Famous Art Forgers]

To their credit, pre-1920s manufacturers attempted to heat and stabilize the pigment, but gave up when their efforts went awry. Matisse's cadmium yellow paint resulted from a precipitation process. "After the bright yellow pigment precipitates out, they would heat it up in air in order to crystallize the pigment," and stabilize the chemical, Mass said. However, the cadmium sulfide would react with the oxygen in the air and form cadmium oxide, which is brown. "So they thought, 'Oh, this is bad, we're ruining our pigments,'" and decided to skip the heating step, Mass said.

After the 1920s, manufacturers started heating the pigment in the presence of nitrogen, which prevented brown cadmium oxide from forming, Mass said. Understanding the chemistry behind how the paints were made and how the paintings are reacting with their environment is "critical for the preservation of the paintings," Mass said.

Van Gogh's artwork is also at the mercy of its environment. Research from a few years ago found that his richly hued "Flowers in a Blue Vase," painted in Paris in 1887, is also fading. Van Gogh's bright-yellow flowers are now more of an orange-gray color. Technical analysis on the painting found that the cadmium yellow pigment was reacting with light and breaking down into compounds that combined with lead from the varnish to form an opaque lead sulfate compound. Researchers working on "The Joy of Life" also observed patches of lead sulfate, but did not publish that finding since the patches weren't widespread, Mass said.

A copy of "The Joy of Life" likely bounced from different owners after its completion in 1906 to when it went into the Barnes Foundation collection in 1922. "There is a possibility, an almost certainty, that there was an uncontrolled environment before it went to the Barnes Foundation," Mass said. Paintings in private homes go through the same degradation process as the cadmium yellow breakdown.

"People need to understand that they need to protect their investments in terms of having the right climate control to preserve the painting," Mass said. Restoring paintings is often not considered acceptable in the art conservation community, Mass said.

"You don't want to remove material from the painting that the artist actually put on himself. It's one thing to remove a prior restoration, but to remove the artist's paint is frowned upon," she said.

The findings were detailed online June 3 in the journal Applied Physics A.

Elizabeth Goldbaum is on Twitter. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus