Oil from BP Spill Coats Miles of Gulf Seafloor

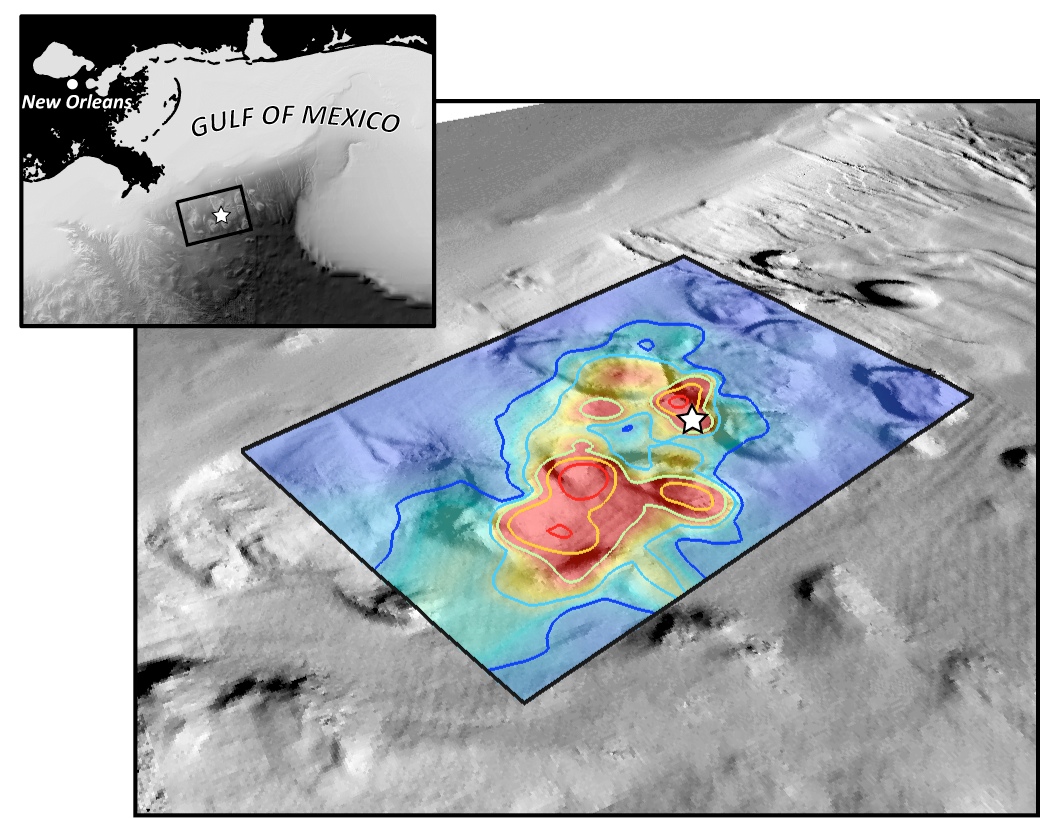

A significant portion of the remaining oil from the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill is sitting on the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico, within 25 miles (40 kilometers) of the well, a new study finds.

The BP-operated Macondo well exploded in April 2010, and gushed an estimated 5 million barrels of oil into the ocean before engineers finally capped the well in July 2010. Since that time, research has suggested that the spilled oil has affected wildlife ranging from dolphins to corals. In 2014, researchers at Pennsylvania State University reported that coral communities up to 13.7 miles (22 km) from the spill site showed damage.

Now, researchers have tracked the path of oil from the water column to the ocean floor, and they found the final resting place of between 2 and 16 percent of the total oil spilled.

"This analysis provides us with, for the first time, some closure on the question, 'Where did the oil go, and how did it get there?'" Don Rice, the program director of the National Science Foundation's Division of Ocean Sciences, said in a statement. The NSF funded the research.

Tracing a spill

Scientists estimate that about 2 million barrels of Deepwater Horizon oil ended up in the deep ocean. Tracing that oil has been challenging. [SOS! 10 Major Oil Disasters at Sea]

A research team led by David Valentine, a microbial geochemist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, sampled more than 534 locations near the spill site, gathering more than 3,000 individual samples. They analyzed the samples for a hydrocarbon called hopane, which is found in oil and persists in the environment for a long time.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers found an area of 1,250 square miles (3,237 square km), mostly southwest of the Macondo well, where a thin sheen of oil rests in patches on the top half-inch of the seafloor, according to the NSF.

"Based on the evidence, our findings suggest that these deposits are from Macondo oil that was first suspended in the deep ocean, then settled to the seafloor without ever reaching the ocean surface," Valentine said in the statement.

Oil damage

The droplets of oil started out 3,500 feet (1,067 meters) below the ocean surface and were caught by deep-ocean currents before raining down another 1,000 feet (305 m) to the seafloor, Valentine said. This hydrocarbon rain explains the damage suffered by coral around the site, he said.

"The pattern of contamination we observe is fully consistent with the Deepwater Horizon event but not with natural seeps," Valentine said.

Much of the deep ocean oil is still missing, however. The portion Valentine and his colleagues traced represents only 4 to 31 percent of the oil thought to be trapped in the depths of the ocean (up to 16 percent of the total oil spilled).

"This knowledge remains largely provisional until we can fully account for the remaining 70 percent," Rice said.

The researchers reported their findings Oct. 27 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.