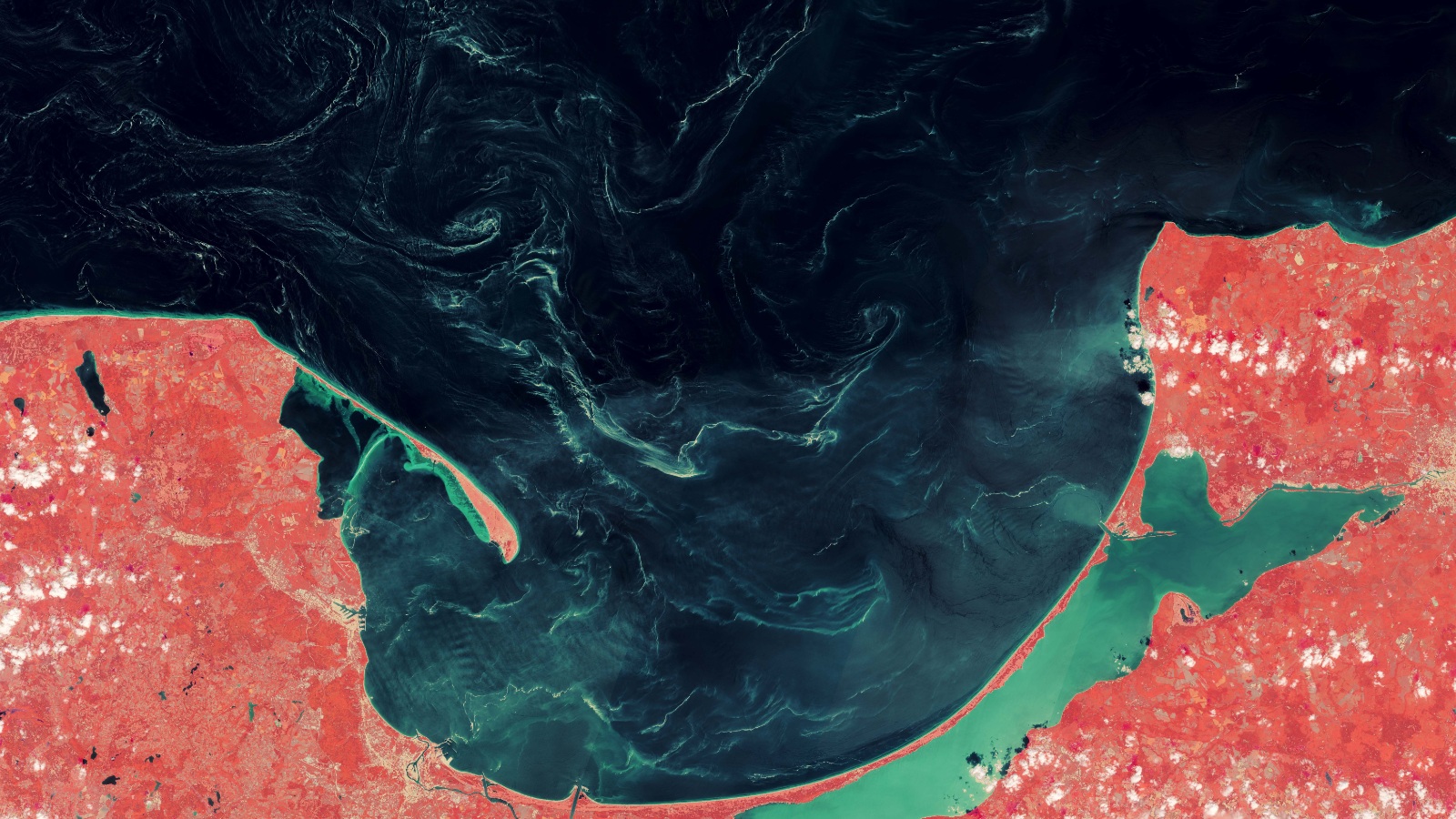

Mysterious substance spotted swirling across the surface of the Baltic Sea — Earth from space

This 2018 satellite photo shows an unknown substance swirling across the Gulf of Gdańsk in Poland. Scientists were shocked to later discover what it really was.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Where is it? Gulf of Gdańsk, Poland [54.49454424, 19.056185969]

What's in the photo? Slicks of organic material swirling on the ocean surface

Which satellite took the photo? European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2A satellite

When was it taken? May 16, 2018

This striking false-color satellite image shows masses of organic material swirling along the Polish coastline. When the photo was taken, the composition of these giant swirls was unknown, but surprising research has since revealed what they are made of.

In 2000, satellite imagery revealed the presence of previously unknown, near-invisible films of organic material, or "slicks," periodically appearing on the ocean surface in and around the Gulf of Gdańsk — a section of the Baltic Sea surrounding the city of Gdańsk on Poland's north coast.

The best example of this intriguing phenomenon occurred in May 2018, when the swirls reached more than 130 miles (210 kilometers) from the coastline, according to NASA's Earth Observatory. The photos of this event (see above and below) have been altered to highlight the wavelengths of light coming from the mystery substance, which also makes the land surrounding Gdańsk appear red.

Scientists were initially unsure what these slicks were made of. They formed similar patterns to photosynthetic algae blooms that get swirled across the ocean surface by wind and ocean currents. However, such blooms are normally clearly visible to the naked eye in most satellite photos, and often emerge several months earlier than when the slicks kept appearing.

Some researchers later proposed that the material could be "sea snot" — a slimy substance produced by some plankton, which can stick to boats and along the coastline. However, locals have never reported any sea snot outbreaks in the area.

Related: See all the best images of Earth from space

But during a 2023 study into the slicks, researchers finally realized what they were made of: tree pollen.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Using data collected by NASA's Terra and Aqua satellites, the study team revealed that similar slicks had appeared 14 times between 2000 and 2001. The timing of these slicks, which often appear between May and June, closely matched the pollen cycle of pine trees (Pinus sylvestris), suggesting that the trees' pollen was being blown out to sea and settling on the ocean's surface.

A further analysis of the light reflected off the slicks confirmed this hypothesis.

Ocean pollen

Pine trees are the most common tree in Poland, making up around 60% of the country's forests, which in turn cover one-third of the nation's landmass, according to State Forests Poland.

Previous research had already shown that the pollen of these trees could end up in the Baltic Sea. But until the 2023 study, there was no indication that this was happening on such a large scale, according to the Earth Observatory.

Due to pollen's high organic carbon content, researchers believe follow-up studies are needed to fully assess the role it plays in marine ecosystems across the globe.

"If we can track pollen aggregation in different places, this may provide useful data for fisheries studies," Chuanmin Hu, an optical oceanographer at the University of South Florida who led the 2023 study, previously told the Earth Observatory.

The amount of pollen reaching the world's oceans is also likely increasing as a result of human-caused climate change: A 2021 study in North America revealed that annual pollen levels increased by 21% between 1990 and 2018, and that the pollen season lasted for around 20 days longer on average. This is the result of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide, which allows plants to produce more pollen — and is happening around the world.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus