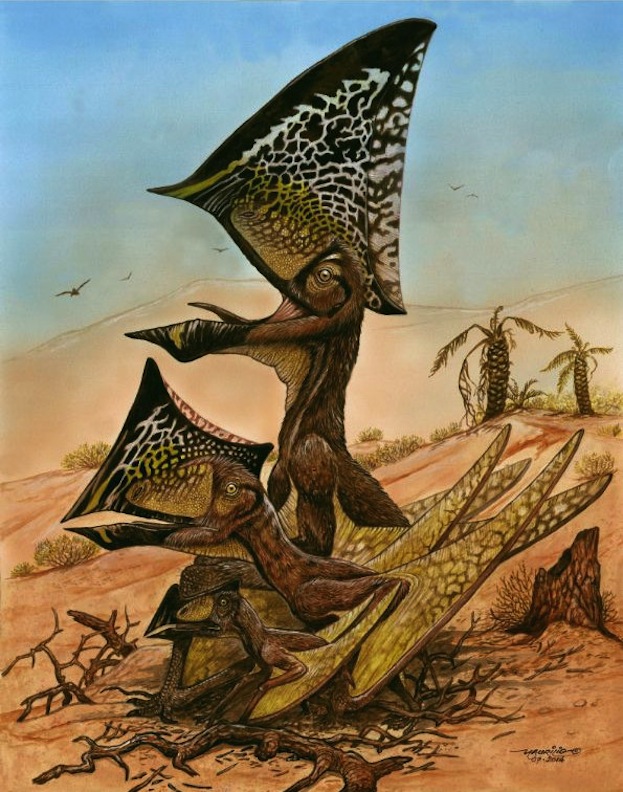

An ancient flying reptile with a bizarre, butterflylike head has been unearthed in Brazil.

The newfound reptile species, Caiuajara dobruskii, lived about 80 million years ago in an ancient desert oasis. The beast sported a strange bony crest on its head that looked like the wings of a butterfly, and had the wingspan needed to take flight at a very young age.

Hundreds of fossils from the reptile were unearthed in a single bone bed, providing the strongest evidence yet that the flying reptiles were social animals, said study co-author Alexander Kellner, a paleontologist at the Museu Nacional/Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro in Brazil. [See Images of the Bizarre 'Butterfly Head' Reptile]

Rare find

Though pterosaur fossils have been unearthed in northern Brazil, no one knew of pterosaurs fossils in the southern part of the country. In the 1970s, a farmer named Dobruski and his son discovered a massive Cretaceous Period bone bed in Cruzeiro do Oeste in southern Brazil, a region not known for any fossils, Kellner said. The find was forgotten for decades, and then rediscovered just two years ago. The team dubbed the reptile Caiuajara dobruskii, after the geologic formation, called the Caiuá Group, where it was found, as well as the farmer who discovered the species, Kellner said.

C. dobruskii belonged to a group of winged reptiles known as pterosaurs, which are more commonly known as pterodactyls.

Hundreds of bone fragments from the species were crammed in an area of just 215 square feet (20 square meters). At least 47 individuals — and possibly hundreds more — were buried at the site. All but a few were juveniles, though the researchers found everything from youngsters with wingspans of just 2.1 feet (0.65 m) long to adults with wingspans reaching 7.71 feet (2.35 m). The fossils weren't crushed, so the 3D structure of the animals was preserved, the authors wrote in a research article published today (Aug. 13) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The ancient reptiles' bony crests changed in size and orientation as the pterosaurs grew.

Because the adult skeletal size (other than the head) wasn't much different from the juveniles', the researchers hypothesized that C. dobruskii was fairly precocious and could fly at a young age, Kellner said.

Water congregation

Based on the sediments in which the bones were found, the area was once a vast desert with a central oasis nestled between the sand dunes, the authors wrote in the paper.

Ancient C. dobruskii colonies may have lived around the lake for long periods of time and died during periods of drought or during storms. As the creatures died, the occasional desert storm would wash their remains into the lake, where the watery burial preserved them indefinitely, the researchers said. Another possibility is that the pterosaurs stopped at this spot during ancient migrations, though the authors suspect that is less likely.

The bone bed, with its hundreds of individuals in well-dated geological layers, is some of the strongest evidence yet that the fruit-eating animals were social, Kellner said.

"This was a flock of pterosaurs," Kellner told Live Science.

This finding, in turn, strengthens evidence that other pterosaur species may have been social as well, the authors wrote in the paper.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.