What’s Behind Super Typhoon’s Rapid Intensification?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

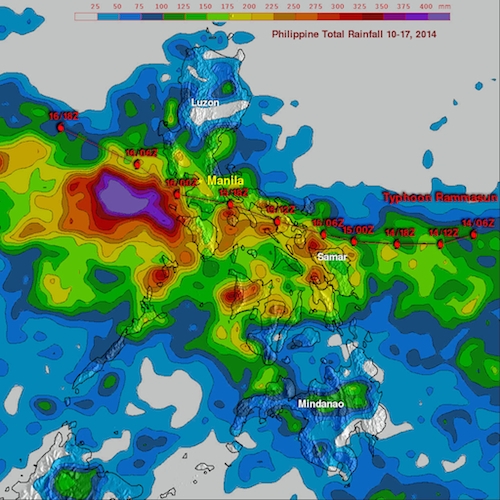

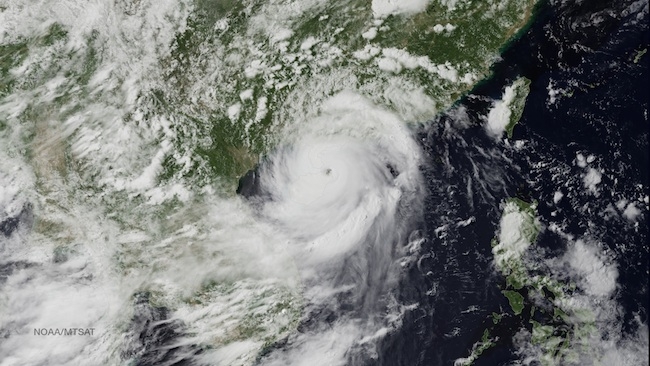

Typhoon Rammasun first tore across the Philippines earlier this week, dumping up to 13 inches of rain in some spots and causing the deaths of at least 40 people. It then emerged over the South China Sea and underwent a rapid re-intensification that boosted it to Super Typhoon status before it hit China’s Hainan Island, becoming the most intense typhoon to hit southern China since 1973, according to the World Meteorological Organization.

Warm ocean waters and a favorable atmospheric environment allowed Rammasun to quickly regroup after its foray over the Philippines left it weakened and somewhat disorganized. While such rapid intensification has been seen many times in tropical cyclones (the blanket term for typhoons and hurricanes), the dynamics of the process aren’t well understood, limiting forecasting abilities.

“Tropical cyclones (known regionally as typhoons) are a bit like snowflakes; no two are alike. Predicting how their intensity will change is notoriously difficult,” said Kerry Emanuel, a MIT meteorologist and climate researcher who has extensively studied the effects of climate change on hurricanes.

Super Typhoon Haiyan: A Hint of What’s to Come? El Nino Expected to Limit 2014 Hurricane Season Here Are 5 Resources to Track Hurricane Season

The warming of ocean waters due to the buildup of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is a concern for the future threat of tropical cyclones, though exactly how climate change will affect the frequency and intensity of storms is an active area of research. Some studies, including some cited in the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, have suggested that storm intensity will increase, but frequency will decline, while others have suggested that both will rise along with warming.

Rammasun began as a Tropical Depression on July 10, strengthened into a tropical storm by the following day and then after traveling over some of the warmest ocean waters on the planet, it ramped up to a full-blown typhoon by the time it made landfall over the Philippines on July 15.

The waters around the Philippines are also some of the fastest warming, as the ocean takes up much of the excess heat from the atmosphere trapped by the rise of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. The sea level rise in the region contributed to the catastrophic storm surge of Super Typhoon Haiyan last fall when it hit some of the same parts of the Philippines that were recently racked by Rammasun.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Haiyan, known in the Philippines as Yolanda, reached a strength equivalent to a Category 5 hurricane and was potentially the most intense storm ever recorded at landfall. Estimates of storm surge reached as high as 24 feet, according to the 2013 State of the Climate report published on Thursday in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Haiyan killed at least 6,300, with 1,000 more still missing, the report said.

Tropical cyclones typically weaken after making landfall, as they become cut off from their source of energy. But Rammasun, called Glenda in the Philippines, threw a curveball and initially failed to follow this pattern.

“This has been a fairly unique cyclone, most notably since it actually continued to strengthen after first making landfall in the Philippines on Tuesday before later weakening while passing just south of Manila,” said Steven Bowen.

“It was rapidly intensifying as it came ashore in the Philippines and for a brief period it was still able to tap into the warm ocean waters to keep fueling itself. Once it moved further over the archipelago, it started to succumb to the frictional effects of land,” Bowen told Climate Central in an email.

Though it weakened as it traveled over the archipelago, Rammasun was intact enough that once it emerged into the favorable environment of warm water and low wind shear over the South China Sea, it became reinvigorated. Wind shear, the change of direction and speed of the wind with height, can tear a storm apart.

“Despite looking fairly ragged, the storm’s core was able to largely remain intact while crossing the Philippines, which is also why it was able to get its act together again in the South China Sea,” Bowen said.

On Thursday, Bowen said that the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (run by the U.S. Navy and Air Force) didn’t expect Rammasun to be much stronger than a high-end Category 3 storm or a weak Category 4. But the storm bucked expectations once again, making landfall with maximum sustained winds estimated at 155 mph, making it at least a strong Category 4 and putting it on the cusp of Category 5 status.

“What can we say about Rammasun other than it’s a storm that continually shunned the forecast intensity models,” Bowen wrote in an email Friday morning. “Any time that a borderline Category 4/5 cyclone makes landfall, it’s a big deal, so Rammasun is certainly going to leave its mark for this year’s season.”

Much of that mark has come from the rains Rammasun has poured on the places it has hit. The rains are a particular concern in southern China, where monsoon rains have already caused extensive flooding in recent weeks.

“Rammasun could really exacerbate the situation across several provinces in the region,” Bowen said.

Global warming is expected toincrease the rainfall from tropical cyclones, “increasing the problem of freshwater flooding from these storms,” Emanuel said. A warmer atmosphere contains more water vapor, which means more rain in storms of many kinds.

The next storm in the western Pacific basin, Tropical Storm Matmo, is now gearing up, and could possibly become a typhoon before hitting Taiwan, though its intensity and track are highly uncertain this far in advance.

You May Also Like Six Months In and Sizzling California Sets Record So You Think You Know Renewables? Take the Quiz Weather Disasters Have Cost the Globe $2.4 Trillion Interactive: 1,001 Blistering Future Summers

Follow the author on Twitter @AndreaTWeather or @ClimateCentral. We're also on Facebook & other social networks. Original article on Climate Central.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus