What 11 Billion People Mean for Climate Change

Editor's note: By the end of this century, Earth may be home to 11 billion people, the United Nations has estimated, earlier than previously expected. As part of a week-long series, LiveScience is exploring what reaching this population milestone might mean for our planet, from our ability to feed that many people to our impact on the other species that call Earth home to our efforts to land on other planets. Check back here each day for the next installment.

On the western coast of Alaska, nestled against the Bering Sea, residents of the remote village of Newtok may soon become the country's first climate refugees.

Like many Alaskan villages, Newtok sits atop permanently frozen soil called permafrost. In recent years, however, warming oceans and milder surface temperatures have melted the icy subsoil, causing the ground beneath Newtok to erode and sink. In 2007, the village already sat below sea level, and studies warned that the subarctic outpost could be completely washed away within a decade.

Now, despite political and financial hurdles, the community is looking to relocate its roughly 350 residents. With climate change rapidly altering human ecosystems around the globe, Newtok may not be alone in its fight against warming temperatures, melting ice and rising seas.

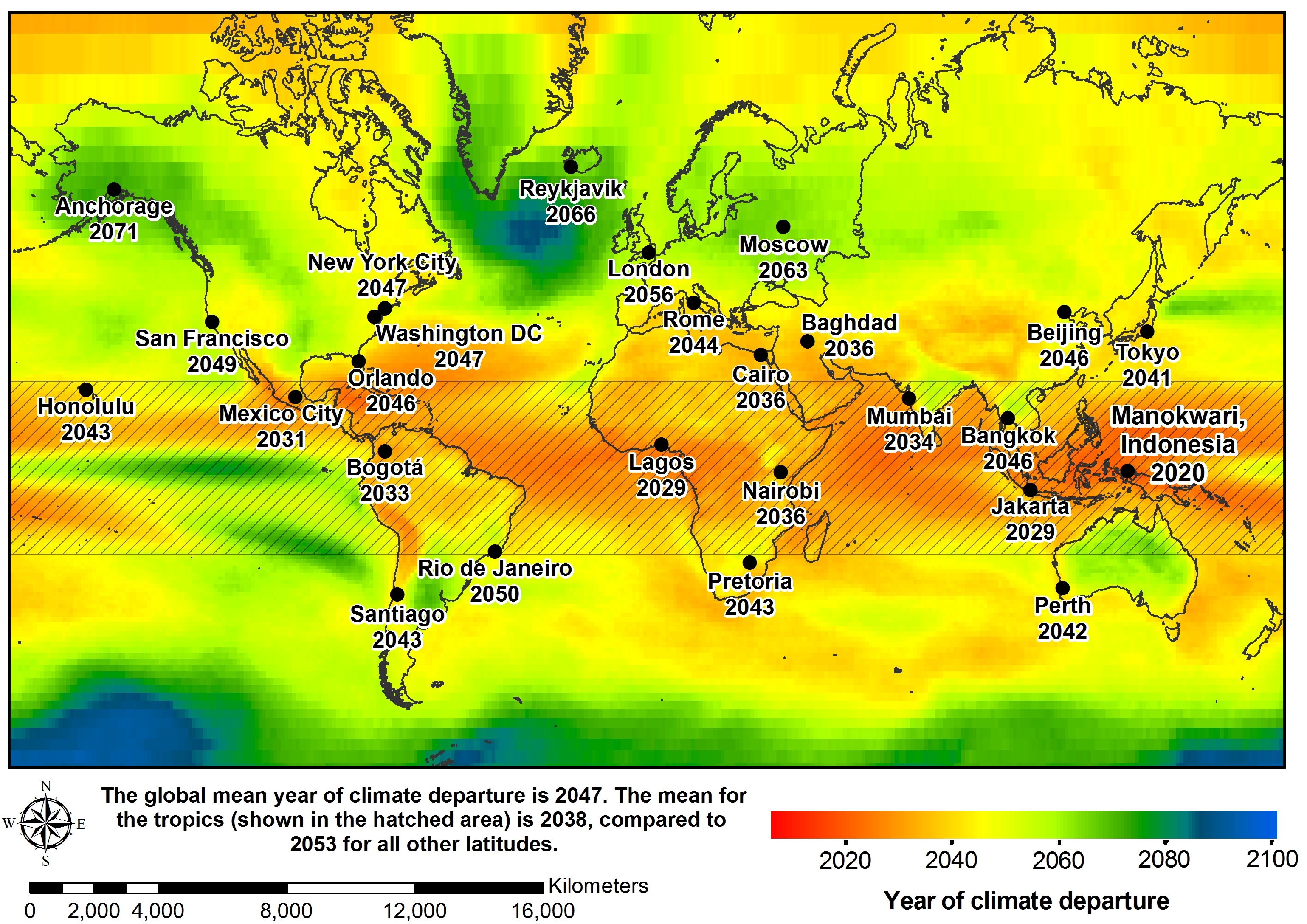

For the roughly 7.2 billion people who live on Earth today, the impacts of a changing climate may be taking different forms, but the consequences are already being felt across the globe — from severe monsoons in Southeast Asia, to the increasing pace of melting ice at the poles, to hotter-than-average temperatures throughout the contiguous United States.

Over the course of the next century, if the levels of greenhouse gas emissions are not reduced, and nations have failed to address the myriad challenges of climate change, scientists say Earth's fragile ecosystem could be in serious jeopardy. But, what if in those same 100 years, nearly 4 billion people are added to the world's population? Could this type of rapid growth overwhelm the carrying capacity of our "Pale Blue Dot" and our ability to mitigate and cope with climate change?

A recent United Nations analysis of world population trends indicates global population growth shows no signs of slowing, with current projections estimating a staggering 11 billion people could inhabit the planet by the year 2100, faster growth than previously anticipated. The majority of this surge in population is likely to occur in sub-Saharan Africa, with the population of Nigeria expected to surpass that of theUnited States before 2050, according to the statistical analysis.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new report also suggests India will eventually become the world's largest country, matching China's estimated population of 1.45 billion people in 2028, and continuing to swell beyond that point, even as China's population begins to decrease.

Some scientists say rapid population growth could be catastrophic for the planet, because it will likely lead to overcrowding in cities, add stress to Earth's already dwindling resources, and worsen the effects of climate change. But within the scientific community, a debate is brewing, and there is little consensus about how — or even if — population growth is linked to global warming.

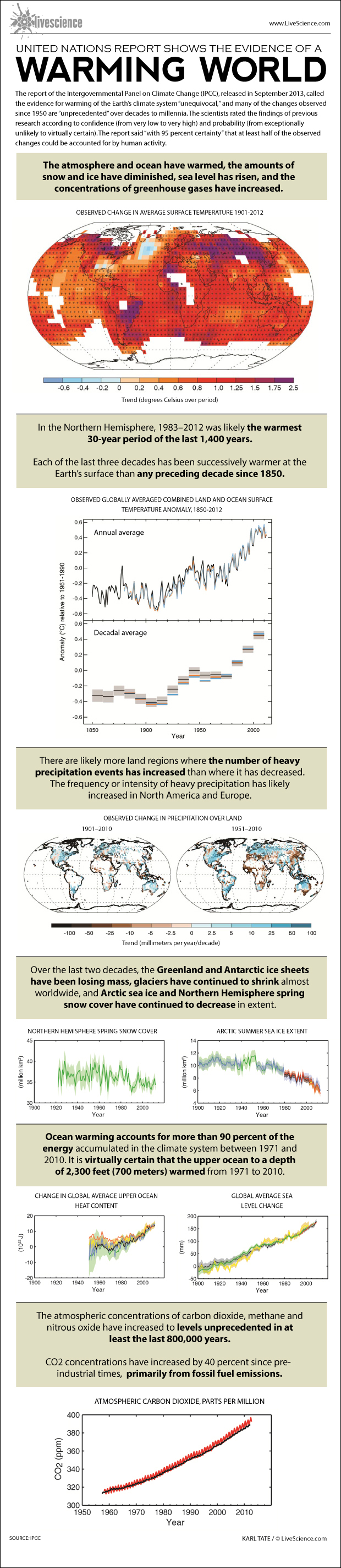

Assessing the impact of population growth on climate change has been tricky. Most scientists agree that humans are to blame for most of the planet's warmingsince 1950, but precisely which events were aggravated by human activities (and how much) are unknown. [What 11 Billion People Mean for the Planet]

"It's a question that's really hard to answer, because climate science is not to the point of being able to identify specific impacts, or changes that have occurred so far, as being directly caused by climate change," said Amy Snover, co-director of the Climate Impacts Group and a researcher at the Center for Science in the Earth System at the University of Washington in Seattle. "What we can do is look at the many things that have happened recently that are similar, and what we expect to happen, and see that these things are problematic and will certainly raise concerns for the future."

Furthermore, scientists on both sides of the equation — those who study demographics and those who study climate science — do not necessarily agree on how, or even if, population growth and climate change are connected.

A growing debate

Increasing the number of people on the planet does not, in itself, intensify climate change, said David Satterthwaite, a senior fellow studying climate change adaptation and human settlements at the International Institute for Environment and Development, in the United Kingdom. Rather, changes in consumption are the key drivers of global warming, he explained.

"Higher consumption is what drives anthropogenic climate change," Satterthwaite told LiveScience. "The high-consumption lifestyles of the richest half-billion people scare me much more than the growth in population in low-income nations."

This is because developing nations, where the U.N. estimates most of the next century's surge in population will occur, have much smaller carbon footprints than developed countries, such as the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom.

"If you think of population as the driving force, it makes sense to look at the fast-growing nations and say: 'We have to slow that population growth,'" Satterthwaite said. "But most of the nations with the fastest growing populations have far lower per capita greenhouse gas emissions."

During the Industrial Revolution, which began in the mid-1700s in England and later spread across the Atlantic Ocean to the United States, emissions of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases soared as manufacturing and transportation boomed. The technologies used during the Industrial Revolution were also inefficient and largely based on coal and fossil fuels, which emit large amounts of greenhouse gases that linger in the atmosphere.

This flurry of activity has taken a toll on the planet. Since the start of the Industrial Revolution, human activities have increased the concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide by a third, according to NASA.

Now, as developing countries seek their own industrial revolution, there are concerns that too much damage has already been done.

"There are opinions that we're already past a sustainable population now, in terms of being able to provide a high quality of life for every citizen on the planet," said David Griggs, a climatologist and director of the Monash Sustainability Institute at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and a former head of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), an international body jointly established by the United Nations Environment Programme and the World Meteorological Organization to assess the environmental and socioeconomic impacts of climate change.

Others say improvements in technology will yield better crop production and distribution, enabling cities and towns to accommodate more people, he added. But more is not necessarily better.

"I'm not a fan of thinking about this as a tipping point — there isn't a point where we just go over the edge," said Griggs, who was previously the deputy chief scientist of the United Kingdom's national weather service. "It's a slow deterioration, and the more people there are, the more challenging it is for those people to have their basic needs met."

Population versus consumption

To understand the potential environmental impacts, it is important to consider both population growth and trends in consumption, said Robert Engelman, president of the Worldwatch Institute, an environment and sustainability think tank based in Washington, D.C.

"Some people will say one matters more than the other, but they multiply each other," Engelman said. "It would be dangerous to ignore population as a major factor."

In 2008, China, the United States, the European Union (excluding Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania), India, the Russian Federation, Japan and Canada were among the top emitters of carbon dioxide. Combined, these nations contributed more than 70 percent of the global carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel combustion and industrial processes. In contrast, the rest of the world represented only 28 percent of carbon dioxide emissions.

"In some of the poorest countries in the world, emissions are very low, but the idea is we want these countries to develop," Engelman said. "As we've seen happen in India and China as they've industrialized, countries that are populous and poor can experience a rapid rise in greenhouse gas emissions. We can't just consider how much the average person is emitting in these populous countries now. We have to think about what will be happening to the people in these countries over the next 70 years."

Beginning in the 1960s, China embarked on a rapid path toward industrialization. By the end of the century, the country had secured its place as a manufacturing powerhouse and a veritable economic superpower. But, China's speedy industrialization has come at an environmental cost.

Within 20 years, China more than tripled its emissions of carbon dioxide — from 2.46 million tons of carbon dioxide in 1990 to 8.29 million tons in 2010, according to United Nations estimates.

Since 2000, China's energy-related greenhouse gas emissions have increased at an average rate of more than 10 percent each year, according to the Harvard Project on International Climate Agreements, which is designed to identify "scientifically sound, economically rational, and politically pragmatic post-2012 international policy architecture for global climate change."

Adding politics to the mix

But, developing climate policies has been a challenging, and an often fruitless, process.

Jerry Karnas, the Center for Biological Diversity's population campaign director in Miami, is all too familiar with these political pitfalls, particularly in addressing the impact of population growth on climate change.

In 2008, Karnas was appointed to a statewide commission to help design a plan for Florida to reduce its carbon dioxide emissions to 80 percent of 1990 levels by the year 2050. The final report was more than 1,000 pages and comprehensively tackled every sector of Florida's economy, except population.

"Population was the only thing not on the table," Karnas said. "We had to take growth as a given, and not challenge the notion that for Florida to succeed, it had to grow."

One of the reasons the state government accepts rapid population growth has to do with the way Florida's economy is set up, Karnas said.

"Florida is a sales tax state. We have no income tax, but much of the state is also funded by the documentary stamp tax," he said. "Documentary stamps are real estate transactions, so every time a real estate transaction occurs, it gets taxed, and that goes into the state coffer. So, the two major funding sources for Florida are dependent on increasing the population numbers in the state."

While the population of the United States is not expected to leap significantly in the next century, diminishing natural resources are already adding stress to the country's food and water supplies, and the availability of future energy resources.

In regions of the world where vast population growth is projected, such as sub-Saharan Africa, the issue of dwindling natural resources will likely be magnified. [5 Places Already Feeling the Effects of Climate Change]

Feeding a hungry planet

If the global population increases by 3 billion people, food production will also need to rise to meet these growing demands. Finding adequate agricultural land, however, will be a challenge, as soil erosion and more frequent droughts related to climate change render larger tracts of land unusable, Griggs, the Monash University climatologist, said.

"If we look at the next 50 years, we'd need to grow more food than we have in the whole of human history to date to feed those 9 billion people," Griggs said. "But since we have no more agricultural land, we'll have to produce all this food on the same land we're producing food on at the moment."

In particular, southern Asia, western Asia and northern Africa have virtually no spare land available to expand agricultural practices, according to the 2013 Statistical Yearbook of the Food and Agricultural Organization for the United Nations, published in June.

More people on Earth also means more competition for water, Griggs added. Currently, one of the main uses for water is in agriculture, and ensuring that populations have access to clean drinking water will be another significant challenge, he said, since global warming may cause arid regions of the planet to become even more parched.

In the United States, the Bureau of Reclamation released a report on the status of the Colorado River Basin in December 2012. The study concluded that over the next 50 years, water supply from the Colorado River will be insufficient to meet the demands of its adjacent states, including Arizona, New Mexico and California.

"The U.S. government was effectively saying, there will be no way to completely satisfy the water needs of the population that is currently projected in that part of the country," Engelman said.

Worldwide, the situation is not much better. A 2011 report on the state of the world's land and water resources, released by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, established that more than 40 percent of the world's rural population lives in water-scarce regions.

Ways to mitigate the impacts

While the impact of population growth on climate change remains a topic of debate, experts agree that finding ways to mitigate the effects of climate change will be critical for the sustainability of the planet.

For one, nations need to address climate change issues now, in order to make communities more resilient in the future, said Declan Conway, a professor of water resources and climate change at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom. This includes investing in renewable energy alternatives, such as technologies to efficiently harness solar and wind energy, he added.

As part of his work at the Worldwatch Institute, Engelman also promotes the idea of carbon taxes, which would introduce fees based on the carbon content of fuels. While these types of resource taxes have been suggested as an incentivized way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, they remain politically divisive.

Still, others see positive changes on the horizon.

"Twenty years ago, climate change wasn't seen as an issue at all, but since then, technology has improved rapidly," Griggs said. "We don't have to hang around and wait for something bad to happen. There's no question that we can deal with all of these climate change issues now, if we want to. The real issue is: Will we? Will there be the political will and the leadership to take on these things?"

As for whether he remains optimistic overall, Griggs is a little more hesitant. "I'm schizophrenic about it," he said. "[At] times, I look at what's happening in the world and the lack of progress, and I say, we're stuffed. On my good days, I'm optimistic and I see us moving in a direction that will allow us to solve these problems."

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.