Where's the Water of the Future? Right Here

NEW YORK — Fresh water. The planet has only so much to meet the needs of a growing world population. And global warming throws more uncertainty into the mix by increasing chances of extreme weather, such as more intense droughts in some places.

Dry spells, such as the devastating drought that gripped much of the United States last year, come with economic costs in the developed world and deadly consequences in poorer countries.

There is no secret source of water of the future. Conservation is the best answer, agreed panelists at a discussion held Thursday (Feb. 28) here at the New York Academy of Sciences.

Better than building

Using the available water is much cheaper than building more reservoirs, pipelines, desalinization plants (to remove salt from seawater) and other infrastructure, said panelist Brian Richter, director of global freshwater strategies for The Nature Conservancy. [Dry and Drying: Images of Drought]

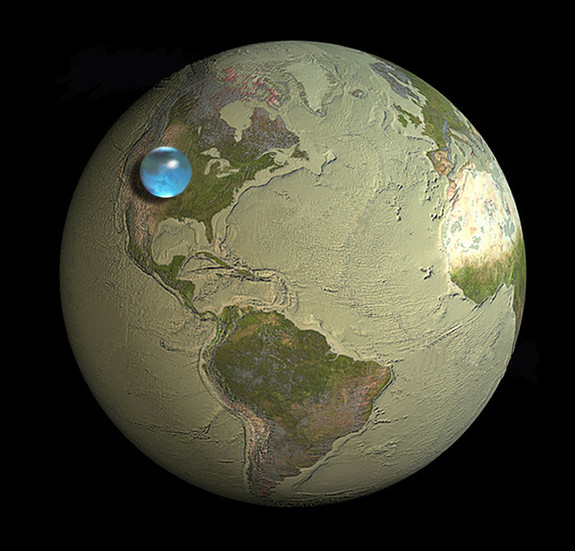

"'I related it to my personal banking account,'" Richter said, quoting a friend. "'If I am overdrafting my personal bank account it is going to do me no good to open up another account.' You can't build your way out of the problem. We are not making any new water."

The good news is, he said, "We're wasting so much, so there is a lot of potential to do a whole lot better."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Curbing demand

History shows that conservation is realistic, said panelist Peter Gleick, co-founder of the nonprofit Pacific Institute.

Between 1900 and 2005, the U.S. gross domestic product (goods and services produced by the economy) grew rapidly. Water use paralleled this growth until 1980, then it leveled off.

"The assumption that our demand for water has to go up with population and economy is a false assumption," Gleick said.

In reality, it is unlikely the United States could have found the water it needed if water withdrawals had continued to grow, he said.

A number of factors tamped down demand for water over the past three decades, he said. Irrigation systems have become more efficient, losing less water to evaporation; Americans are eating less beef, which requires water to raise; toilets, washing machines and industrial processes require less water; Americans are reusing treated wastewater, although "we don't do it much and could do it more," Gleick said.

In fact, wastewater treatment infrastructure could be distributed within particular areas, rather than centralized in a single plant, allowing water to be recycled within those areas. Wastewater would be treated, redistributed to users, then returned for treatment, reducing the substantial costs associated with pumping water across long distances, noted Upmanu Lall of Columbia University's The Earth Institute.

At its source

New York City itself offers an example of good planning, said Adam Freed, director of the Nature Conservancy’s Global Security Water Program, who said that cities are often focal points for the global water crisis. [Earth in the Balance: 7 Crucial Tipping Points]

About 2,000 square miles (5,180 square kilometers) of watershed (land that drains into a particular waterway) has been set aside in the Catskill Mountains and the Hudson River Valley to supply the city with clean water. By investing in protecting the watershed from pollution, the city has saved itself the much larger costs associated with treating the water it needs, Freed said.

This strategy of protecting the water at its source needs to be replicated elsewhere, he said.

Water and money

The private sector has an important role to play, said Brooke Barton, who leads the water program of Ceres, an organization that advocates for sustainable leadership in business.

A number of large companies, such as Coca-Cola and Ford, have recently made commitments to address water use. But the private sector still has far to go, she said. In a study conducted last year, Ceres researchers found that many large companies were far behind the curve with regard to water conservation, Barton said.

The investment community is likely to play an important role in change by pushing companies to gather more data about risks associated with water use, she said.

The cost of water use is often hidden, changing water's price could affect usage, just as gas consumption changes with price, Richter pointed out, with a caveat: "We do have to be careful not to raise the price out of the [range of] affordability of the poor.”

Future climate

Warming brought by climate change is expected to intensify the water cycle — the processes by which water travels between the oceans, land and atmosphere — by increasing evaporation. This is expected to cause changes in extreme weather, including more heat waves and heavy downpours, as well as intense droughts in some, not necessarily the same, places.

These changes will affect water resources, Gleick said.

“Our water systems were designed for yesterday’s climate, and managed for yesterday’s climate,” he said.

Although current changes are the result of human activity, climate change itself isn’t a new phenomenon. Lall said that in the past, nature has shown great variability, at least as large as anything projected for the future. Knowledge of this history can provide a place to start with regard to adaptation, he said.

"We have to deal with variability," Gleick said. "But climate change may also impose unexpected problems that our past experience isn't sufficient to deal with."

Author and journalist Fred Pearce moderated the discussion.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus