Master of Disaster: Hurricane-hunting Drone Proves Game-Changer

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

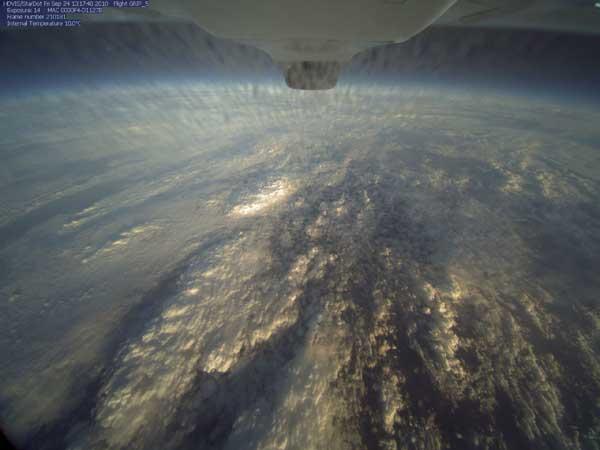

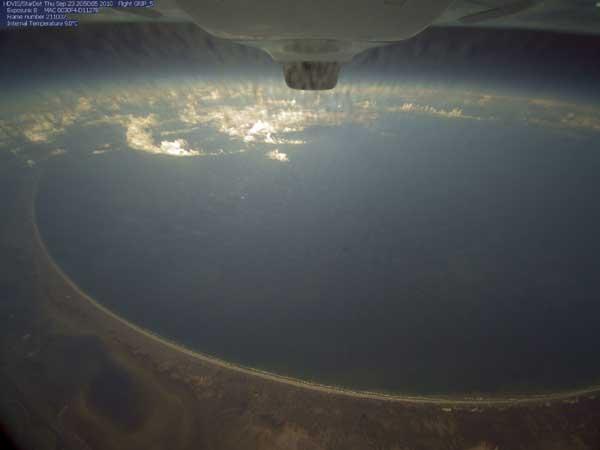

NASA's hurricane-hunting aircraft have been busy this summer, soaring through some of the season's biggest storms. And this year, they have some powerful new company.

For the first time, an unmanned drone the Global Hawk is being used for research inside hurricanes .

"It's a game-changer," said Scott Braun, a mission scientist with NASA's hurricane field study, the Genesis and Rapid Intensification Processes mission, or GRIP experiment .

"We've been able to get to storms that would otherwise be difficult to get to, and been able to spend a lot more time over the storms than would be possible with conventional aircraft," Braun told OurAmazingPlanet, speaking from the plane's home base at the Dryden Research Flight Center in California.

Yesterday (Sept. 23), the Global Hawk flew to a developing storm system in the Caribbean, which grew into Tropical Storm Matthew overnight. The aircraft flew 11 passes over the center of the storm, and touched down back at Dryden around 10 a.m. local time today (Sept. 24).

Instruments aboard the unmanned aircraft capture invaluable data for scientists like Braun, who are studying the mysterious mechanisms that allow some hurricanes to go nuclear, while others fall apart and limp softly off the map.

And though the drone is called "unmanned," it still has pilots guiding it they're just sitting safely back in a control room on the ground instead of fastened in to the plane.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A face only a mother could love

Although its name evokes a graceful figure, the Global Hawk looks more like an eyeless rabbit than a sleek raptor. The plane's windowless, blunt-nose fuselage is dwarfed by vast, spindly 116-foot-(35-meter-) long wings.

However, looks don't really matter when sheer power is the game at hand. The drone can fly up to 12,700 miles (20,438 kilometers) that's half the circumference of the Earth and for 30 hours in a single flight.

The Global Hawk has already checked out Hurricanes Karl and Earl and Tropical Storm Frank so far this season .

Hey, these things don't fly themselves

Dee Porter, a seasoned Air Force pilot, is one of the men behind the controls of the Global Hawk at its base in the Mojave Desert, where the control room is set up to mimic the inside a real plane: pilot and co-pilot in the front, and behind a huge plate-glass window, the crowd of mission scientists conducting the research.

"Imagine the Kennedy Space Center control room, only not quite on that scale," said Porter, who flew U-2 aircraft for almost three decades before NASA tapped him to pilot drones two years ago.

Porter sits in front of four 21-inch monitors, a keyboard and a mouse. That's all it takes to fly the Global Hawk.

"It's completely autonomous," Porter told OurAmazingPlanet. "Once I push the takeoff button and push execute, the airplane could take off, fly 25 hours, come back and land. I could go home."

But flights aren't quite that simple. Pilots monitor the plane's every move, and take over when the Hawk gets to a storm.

"When we're over hurricanes, we will do what is called 'override.' We will direct the airplane to where I want it and at what altitude I want it," Porter said in an interview.

"It's very intense," he said. When we're over a storm, it's very intense."

Porter said he didn't think anything could beat flying a U-2, but flying the Global Hawk into hurricanes to collect data scientists previously couldn't get to is immensely satisfying.

"You watch these scientists and they're just giddy, they're like kids on Christmas morning," Porter said.

The expert flier could just as well be describing himself.

"It's a challenge, the team we've got here is just tremendous. I wake up every morning and I can't wait to get to work," Porter said. "Literally. I wake up early and I'll lie there and toss and turn until I can get up and get ready. I love coming to work."

According to the most recent available pilot schedule, Porter was slated for the last third of the Global Hawk's latest 26-hour flight, which would have put him at the controls as the plane touched down this morning.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus