First Stars in the Universe May Soon Be Detected

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

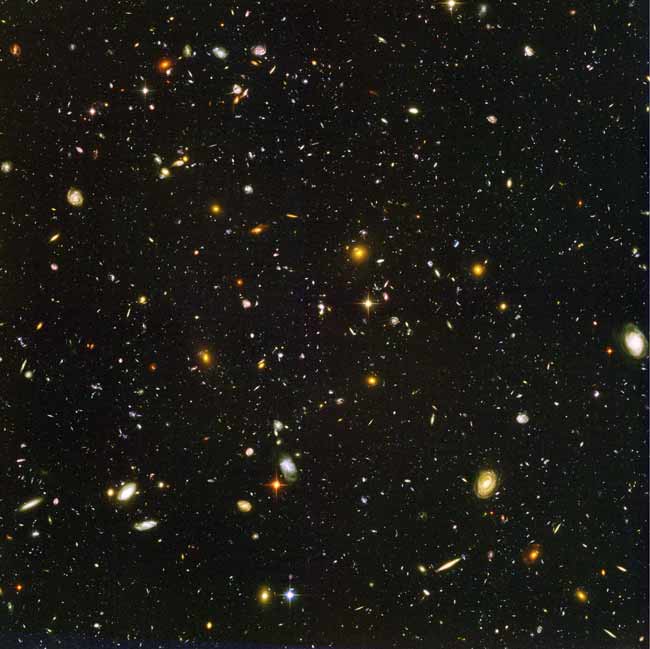

The first stars in the universe may one day be detectable by the unique way they likely spread across space, researchers say.

The cosmos was born in the Big Bang about 13.7 billion years ago, and the first stars in the universe are thought to have lit up about 100 million years afterward,when gas finally gathered in clumps dense enough to collapse under their own gravity and ignite nuclear fusion. However, it remains very difficult to determine when exactly these stars were born or much else about them, since their faraway light is largely obscured by closer sources.

Now the circumstances under which these stars formed could lead to patterns in how they are spread throughout space that astronomers could soon detect.

The first stars formed when clouds of gas bunched together due not only to the pull of their own gravity, but also that ofdark matter. This invisible substance apparently makes up five-sixths of the universe's matter, and its gravitational attraction is what's thought to hold galaxies together.

Dark matter seems to be largely intangible, which means light (and everything else) very rarely bounces off it. Because the collision of light particles with normal matter particles contributes to their movement, normal matter began traveling at a different speed from dark matter in the early universe. [Gallery: History & Structure of the Universe]

Normal matter at times moved too fast for dark matter to capture with its gravity, much as rockets flying at escape velocity can pull away from Earth. This would have led to less clustering of matter, and fewer birthplaces of stars than once thought, study author Rennan Barkana, an astrophysicist at Tel Aviv University in Israel, told SPACE.com.

Based on these differences in speed between normal and dark matter, as well as how radiation from the earliest stars would have influenced stars forming soon after them, the researchers calculated where the first stars would have appeared in the first 180 million years of the universe on the largest cosmic time scales. They found a distinct pattern in the distribution of these stars, which upcoming telescopes such as the Murchison Widefield Array in Australia — a radio observatory under construction now — could detect. "This signal is larger than before thought," Barkana said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, current radio telescopes are not sharp enough to image any specific examples of these first stars; they can see them only en masse. Still, by looking at them all together, "we can get statistics on them, average out all their information and learn about them that way," Barkana said.

The scientists detailed their findings online June 20 in the journal Nature.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom, Facebook& Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus