Bird Flu More Prevalent, Less Deadly Than Expected

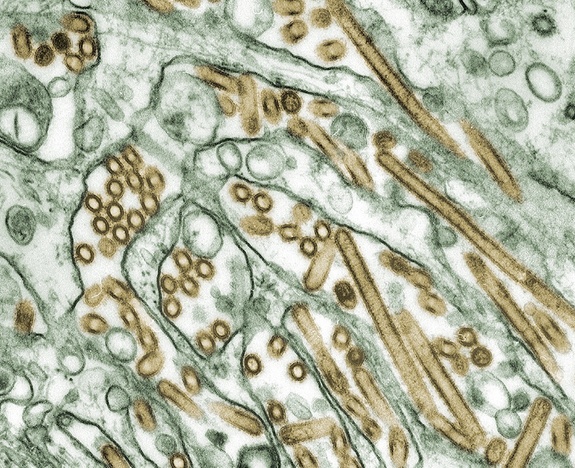

The H5N1 influenza virus, also known as "bird flu," may well be more prevalent and less deadly than health officials had thought, according to a new study published online today (Feb. 23) by the journal Science.

The World Health Organization (WHO) reported 586 human cases of the H5N1 flu since 2003, and notes that as of Feb. 22, 59 percent (346 individuals) of those people had died.

But this 50-percent-plus mortality rate may be misleading, according to the new study led by Peter Palese, chairman of the department of microbiology at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. That's because the cases reported by WHO include only people who were sick enough to go to a hospital and be laboratory-tested for the virus. For WHO, to get counted, a person must have an acute illness and fever within a week and test positive for exposure to the H5 protein that gives the virus part of its name.

Anyone sick enough to do that is more likely to die to begin with, and in countries where avian flu is present, access to health care and hospitals is spotty, according to Palese. Basically, there could be a lot more people out there who get the virus and either don't show symptoms or don't feel bad enough to see a doctor. [Take LiveScience's Bird Flu Quiz]

Palese and his colleagues looked at 20 studies of H5N1 incidence rates, doing what is called a meta-analysis, or a study of studies. Those studies involved a total of 12,677 people. They found that among that group, which was likely to have been exposed, about 1.2 percent on average were "seropositive" — showing antibodies to the virus. In each study the percentage of people whose blood serum showed evidence of a prior H5N1 infection ranged from 0 to 11.7 percent, though the last figure came from people living in close quarters with those who were infected. But none of these groups includes people who didn't end up in a hospital or clinic.

The big question is how that translates to the rest of the population. Even a 2 percent infection rate is a lot of people in a group of millions — say, a city the size of Bangkok. But if the WHO is seeing only those who get to the hospital, it's likely that the number of people with the virus is higher, the researchers say. That means the death rate would be lower.

Even so, that doesn't mean H5N1 is benign. But it does mean that until someone studies whole populations and checks how many people with the virus show fewer severe effects, it is difficult to say exactly how dangerous H5N1 is.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Not everyone is happy with the work. Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, which studies threats of bioterrorism, says there are flaws in the methods used.

For instance, one of the studies included in the analysis looked at the 1997 bird-flu outbreak in Hong Kong, which, Osterholm said, raises the number of people who were seropositive. "The virus was a bit different," he noted. In a press release from the American Society of Microbiology, Osterholm says the Hong Kong, the virus was H1N1, which is also influenza but genetically different from H5N1.

"Peter [Palese]'s paper just confuses the issue because of the Hong Kong experience," Osterholm told LiveScience, adding that only more recent studies, of a virus more similar to that plaguing humans today, should be used. In fact, doing so would reveal that 0.5 percent of the participants were seropositive. He plans to publish a study in the journal mBio tomorrow (Feb. 24) showing that the virus might be even more deadly than the current mortality rate shows. (Palese's paper does consider the Hong Kong outbreak separately and gets the same numbers as Osterholm.)

Taking an average of the studies Palese used, Osterholm said, is therefore misleading. "If you put your head in the freezer and your feet in the oven, of course the average temperature will be just right," he said.

Vincent Racaniello, professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University in New York, said he thinks the study is a good one, and points to the next step of looking at larger populations that aren't going to hospitals. He added that if it turns out many more people are infected than get sick, H5N1 may look a lot less scary. "Until we do that there's no way to know," Racaniello said. He also noted that Palese's study refers to H5N1 studies in Hong Kong, not H1N1 as Osterholm claims.

Another factor will be how easy it is to get the virus in the first place. People who work with poultry are obviously more likely to be exposed. But the virus doesn't seem to transmit well in its wild state from person to person.

H5N1 is usually only present in birds. The protein H5 only connects to a molecule called alpha 2,3 linked sialic acid. (The "linked" part is between two carbon atoms). Birds have that receptor in their respiratory and digestive tracts. Humans have it as well, but it is deeper in the lungs and harder for the virus to reach. Flu viruses that infect humans link to a receptor called alpha 2,6, which resides in mammals' respiratory systems.

This study comes on the heels of controversy surrounding experiments with H5N1 by Ron Fouchier at the Erasmus Medical Center in the Netherlands and Yoshihiro Kawaoka the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Those experiments showed that H5N1 could be modified enough to survive in the air and be transmitted between mammals like ferrets.

Some experts called for withholding the research or at least redacting certain data from publication (Fouchier's and Kawaoka's papers were published in Science and Nature, respectively). They cited the danger that somebody might try using that data to create a biological weapon. Others urged openness in order to understand better how such viruses can evolve into more dangerous forms.

This paper will be published online by the journal Science, at the Science Express website.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.