Action Video Games Improve Vision

Video games with lots of action, such as the shoot-'em-up variety, can improve your vision, a new study finds.

Players became up to 58 percent better at perceiving fine contrast differences in the tests.

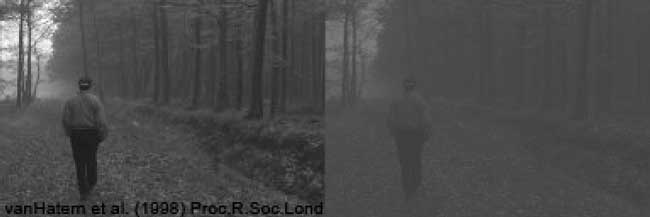

"If you are driving at dusk with light fog it could make the difference between seeing the car in front of you or not seeing it," study leader Daphne Bavelier told LiveScience.

The ability to discern slight differences in shades of gray, or contrast sensitivity, is the primary limiting factor in how well one sees, said Bavelier, a professor of brain and cognitive sciences at the University of Rochester.

"Normally, improving contrast sensitivity means getting glasses or eye surgery—somehow changing the optics of the eye," she said. "But we've found that action video games train the brain to process the existing visual information more efficiently, and the improvements last for months after game play stopped."

The new finding suggests action video game used as training devices may be a useful complement to eye-correction techniques, Bavelier said, since it may teach the brain's visual cortex to make better use of the information it receives.

In 2007, Bavelier found that action video games substantially increase a player's ability to accurately see objects in a cluttered space. A study at the University of Oregon found that some video games improve the ability of children age 4 to 6 to focus their attention, also by training the brain.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the new study, her team tested the contrast sensitivity function of 22 students, then divided them into two groups: One group played the action video games "Unreal Tournament 2004" and "Call of Duty 2." The other played "The Sims 2," which is richly visual, but does not require as much visual-motor coordination.

The volunteers each played 50 hours during the 9-week test. Then their vision was tested again.

Those who played the action games showed an average 43 percent improvement in their ability to discern close shades of gray — close to the difference Bavelier had previously observed between game players and non-game players — whereas the Sims players showed no improvement.

When comparing people who played action video games routinely for more than six months to those who do not play them, the increase was 58 percent, Bavelier said.

"To the best of our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that contrast sensitivity can be improved by simple training," says Bavelier. "When people play action games, they're changing the brain's pathway responsible for visual processing. These games push the human visual system to the limits and the brain adapts to it, and we've seen the positive effect remains even two years after the training was over."

So despite concerns that time spent playing action video games could be bad for people, that time may not necessarily be harmful, at least for vision, she said.

The research, funded by the National Eye Institute and the Office of Naval Research, is detailed today in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

- What is 20/20 Vision?

- World of Warcraft Video Game Succeeds in School

- Video Games Can Improve Kids' Attention

{{ video="attentiontraining" title="Attention Training: Games that are Good for Kids" caption=""You give us 5 days, we'll improve your child's attention!" That’s what these experimental video games could claim. Researchers can train the network of brain areas involved in attention and cognitive focus, which development greatly between ages three an Credit: ScienCentral" }}

Robert is an independent health and science journalist and writer based in Phoenix, Arizona. He is a former editor-in-chief of Live Science with over 20 years of experience as a reporter and editor. He has worked on websites such as Space.com and Tom's Guide, and is a contributor on Medium, covering how we age and how to optimize the mind and body through time. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus