Human Ancestors Were Homemakers

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In a stone-age version of "Iron Chef," early humans were dividing their living spaces into kitchens and work areas much earlier than previously thought, a new study found.

So rather than cooking and eating in the same area where they snoozed, early humans demarcated such living quarters.

Archaeologists discovered evidence of this coordinated living at a hominid site at Gesher Benot Ya‘aqov, Israel from about 800,000 years ago. Scientists aren't sure exactly who lived there, but it predates the appearance of modern humans, so it was likely a human ancestor such as Homo erectus.

Yet this advanced organizational skill was thought to be a marker of modern human intelligence. Before now, the only concrete proof for divided living spaces dated back to only 100,000 years ago.

"Seeing this at such an early site was surprising," said archaeozoologist Rivka Rabinovich of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. "This means there was some ability or some need or requirement of organization."

Rabinovich and her colleagues, led by Nira Alperson-Afil, also of the University of Jerusalem, published their findings in the Dec. 18 issue of the journal Science.

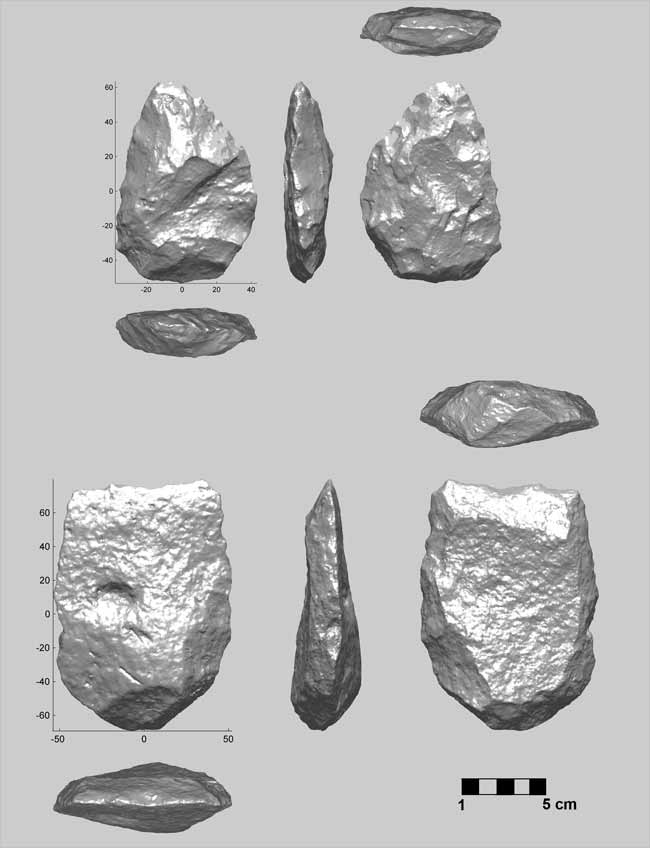

The researchers excavated the remains of an early human encampment on the shores of an ancient lake. They found used pieces of flint, rock tools, crab shells, fish bones, and bits of fruits, seeds, nuts, bark and wood.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The excavation proved that the hominids living there were hunting not just land mammals, but sea creatures like fish, crabs and turtles. And these remains were not scattered randomly, but instead concentrated in certain areas. The food remains and stone-tool bits were found in one area, while the flint scraps (likely from cooking tools) were clustered in another region.

The scientists think the camp's hearth was located in the southeast area of the site, and that food-making and eating took place mostly near there. In addition, most of the stone-tool remains — bits of basalt and limestone rocks that had been shaped into usable instruments — were also clustered near the hearth.

In contrast, the northwestern region held most of the flint remains and evidence of fish preparation. The archaeologists think this could have been a working area for the early human inhabitants.

"The designation of different areas for different activities indicates a formalized conceptualization of living space, often considered to reflect sophisticated cognition and thought to be unique to Homo sapiens," the researchers wrote in the Science paper.

This skill also indicates the inhabitants had some kind of social organization and coordination between individuals.

"It clearly shows that they're much more advanced than we previously thought," co-author Irit Zohar of the University of Haifa told LiveScience.

- Top 10 Things that Make Humans Special

- Peace or War? How Early Humans Behaved

- Top 10 Missing Links

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus