Inside the Brain: Museum Exhibit Will Blow Your Mind

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

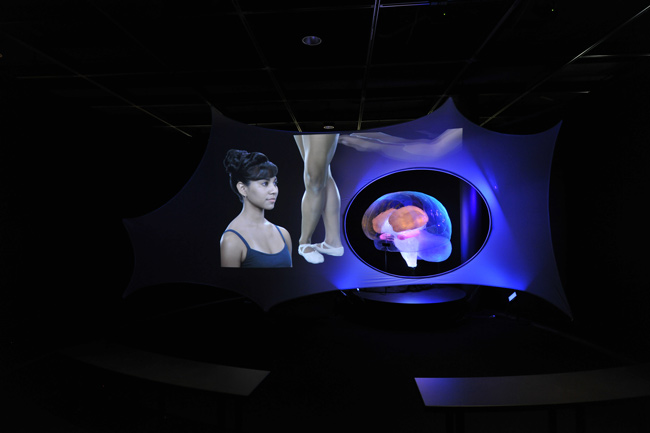

NEW YORK – Bars of light passing across a massive tangle of cables give the sense of being surrounded by crackling electrical signals and firing neurons as you enter the American Museum of Natural History's new exhibit here. Most people may visit the museum for the fossils, but this time they'll want to stay for the brains.

First-time attendees at a preview event on Tuesday (Nov. 16) paused at the entrance to gaze upon a 3-pound preserved brain that looked unremarkably pale and placid compared with what lay ahead. As visitors journey deeper into the exhibit, they encounter an interactive sensory feast that both surprises and stimulates.

The exhibit, called "Brain: The Inside Story," represents a bit of a departure for the museum, said Joy Hirsch, director of the functional MRI Research Center at Columbia University. She consulted on the exhibit as an expert on brain imaging, but confessed to being floored when she saw everything come to life for the first time.

"Museum exhibits like this are traditionally about fossils, about things other than who we are," Hirsch said.

As she spoke, a raised circular pedestal on the exhibit floor showed a spinning movie of brain images of accomplished people such as cellist Yo-Yo Ma and basketball player Landry Fields of the New York Knicks. Hirsch's lab used functional magnetic imaging (fMRI) scans to record brain activity of the celebrities as they looked at photos and listened to themselves at work.

That was "to make the point that all of us are the product of our brains," Hirsch told LiveScience. "Whatever we do and feel and hear and experience is coded by our brains."

Members of the public can check out the exhibit during its run from Nov. 20, 2010 until Aug. 15, 2011.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Look and listen

The brain exhibit quickly immerses visitors by inviting them to look, listen and touch. A person might linger to play a quick brain-training game designed to boost their ability to process visual signals – just as past studies have shown how shoot-'em-up video games can improve a player's abilities to see visual contrasts.

Pausing at another display allows visitors to consider why a sizzling sound is heard differently depending on the image being viewed , or why 98 percent of people in a famous study identified two distinct shapes by the names of either Kiki or Booba – examples of how stimuli can prime our brains to consider the world differently.

Many first-timers stopped to chat with artist Devorah Sperber about her installation that recreates a well-known painting by using stacked thread spools. The effect is to create an upside-down, low-resolution image that "would be like a postage stamp" at 100-percent clarity on a computer screen, Sperber explained.

Only when people peer through a viewing glass does the visual puzzle come together. But the element of surprise and not knowing is crucial.

"I'm the only person who has never experienced my own work, because I know what it is up front," Sperber said. "So my only option to experience it is to watch other people experience it."

Brain evolution

Brain facts designed to astound anyone but the most jaded neuroscientist appear throughout the exhibit. A single neuron can send 1,000 signals per second, each traveling at a sizzling 250 mph (400 km/h). Then there's the early growth spurt most people don't think about – half a million brain cells form every minute during the first five months in the womb.

The dizzying spread of information all comes together nicely through the exhibit's step-by-step presentation. After playing around with the senses, visitors encounter the evolution of the brain from the most basic functions and emotions up through the development of higher thinking in the brain's outer layers – the cortex and prefrontal cortex.

Past brain research usually focused on cognition and thinking, but modern researchers eventually began to consider the illogical, irrational side of the brain.

The limbic system of the brain, where emotions originate, can have a strong influence on thinking so that it seems to run the show, said Margaret Zellner, a behavioral neuroscientist and psychoanalyst who is a postdoctoral fellow at The Rockefeller University. She consulted on the exhibit along with Hirsch.

"If the cortex was all that powerful, we would all be thin and nobody would have a drug addiction," Zellner joked. "We'd be thin, abstinent creatures who were not polluting the planet and driving global warming."

Opening up the mind

Packing all this information into the exhibit presented a daunting challenge for museum curators and researchers who wanted to inform — rather than overwhelm — visitor brains. But Zellner praised the exhibit as a great introduction to the brain for people ranging from middle school students to adults.

"There's so much that is not here in the exhibit just because the world of the brain is like a universe unto itself," Zellner said. "But I think that this is really the best introduction to the brain that I've ever seen in terms of the breadth of what's covered – it hits all the basic building blocks that you need to have some familiarity with."

Beyond the brain's evolution, examples of memory, language and decision-making show visitors how the brain grows and develops. There's even a sneak peek at future brain technologies of the 21st century, and some discussion of how brain implants, bionic eyes and other enhancements could change what it means to be human.

But the improved understanding of the brain over the past decade has already changed much, according to Rob DeSalle, curator of the exhibit and a researcher in the museum's Sackler Institute For Comparative Genetics. Both brain imaging technologies and genomic understanding of the brain have come a long way, as have understanding the emotional brain.

"It would have been completely different … it would have been a very different exhibition," DeSalle said. "Every year there's an order of magnitude leap in what we know and there's still many many order of magnitude leaps that we need to take in the near future."

- 10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain

- Brain Scans Reveal Difference Between Neanderthals and Us

- Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus