Chimps Do Numbers Better Than Humans

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Young chimps apparently have an extraordinary ability to remember numerals and recall them even better than human adults do.

Although researchers have extensively studied chimpanzee memory in the past, the general assumption has been that it is inferior to that of humans, as with many other mental functions.

"There are still many people, including many biologists, who believe that humans are superior to chimpanzees in all cognitive functions," said researcher Tetsuro Matsuzawa, director of the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University in Japan. "No one can imagine that chimpanzees—young chimpanzees at the age of 5—have a better performance in a memory task than humans."

Now Matsuzawa said he and his colleagues "show for the first time that young chimpanzees have an extraordinary working memory capability for numerical recollection—better than that of human adults tested in the same apparatus, following the same procedure."

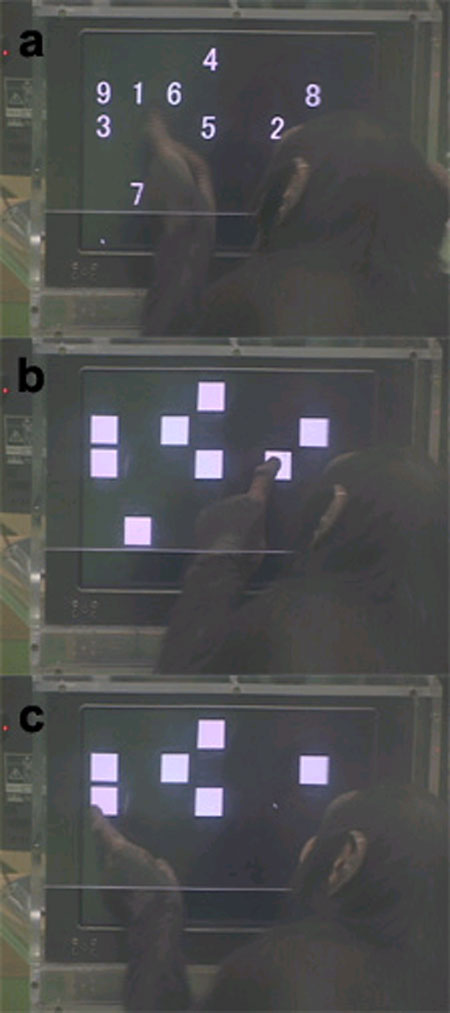

The scientists tested three pairs of mother and infant chimpanzees against nine university students in a memory task involving numerals. All of the chimps had already learned the ascending order of Arabic numerals, from 1 to 9.

The chimpanzees and humans were each briefly shown four to nine numerals at a time scattered across a touchscreen. Those numbers were then all simultaneously replaced with blank squares. The volunteers then had to recall which numeral appeared in which place and touch the squares in ascending order, from lowest to highest. The chimps were rewarded with raisins or apple cubes for correct answers.

The scientists unsurprisingly found that people got worse the less time the numerals spent onscreen. However, they discovered the three young chimps could remember many numerals with a glance, with virtually no change in performance even when the numbers were flashed for just 210 milliseconds—roughly twice as long as a blink of an eye and not enough time for human vision to wander across a screen.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In general, the young chimps performed better than their mothers and adult humans.

"Young chimpanzees are superior to human adults in the immediate memory of details," Matsuzawa told LiveScience.

Matsuzawa said the young chimps' ability resembled photographic memory, the ability in humans to retain a detailed and accurate picture of a complex scene or pattern. This talent—also known as eidetic imagery—is also known to decline with age, as it seems to do in chimps.

A sharp memory could prove useful to chimps in the wild.

"Suppose that a group of males met an adjacent group in the patrol of the territory. It is important to know how many enemies and where (they are) in the bush at a glance," Matsuzawa said. Or "suppose that a chimpanzee arrived at a huge fig tree. It is important to know where the red ripe fruits are, against green ones. It is also important to know the positions of top-ranking males. You cannot eat fruits near the high-ranking males."

As to why chimpanzees—humanity's closest living relatives—have such a strong talent compared to most humans, Matsuzawa speculated there was an evolutionary tradeoff between this kind of sharp memory and the higher mental functions seen in humans, such as our advanced capability for language.

The research by Matsuzawa and his colleague Sana Inoue is detailed in the Dec. 4 issue of the journal Current Biology.

- Video: Chimps Do Numbers

- 10 Amazing Things You Didn't Know about Animals

- Amazing Animal Abilities

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus