Victorians Had Their Own Version of Netflix: 'Magic Lanterns'

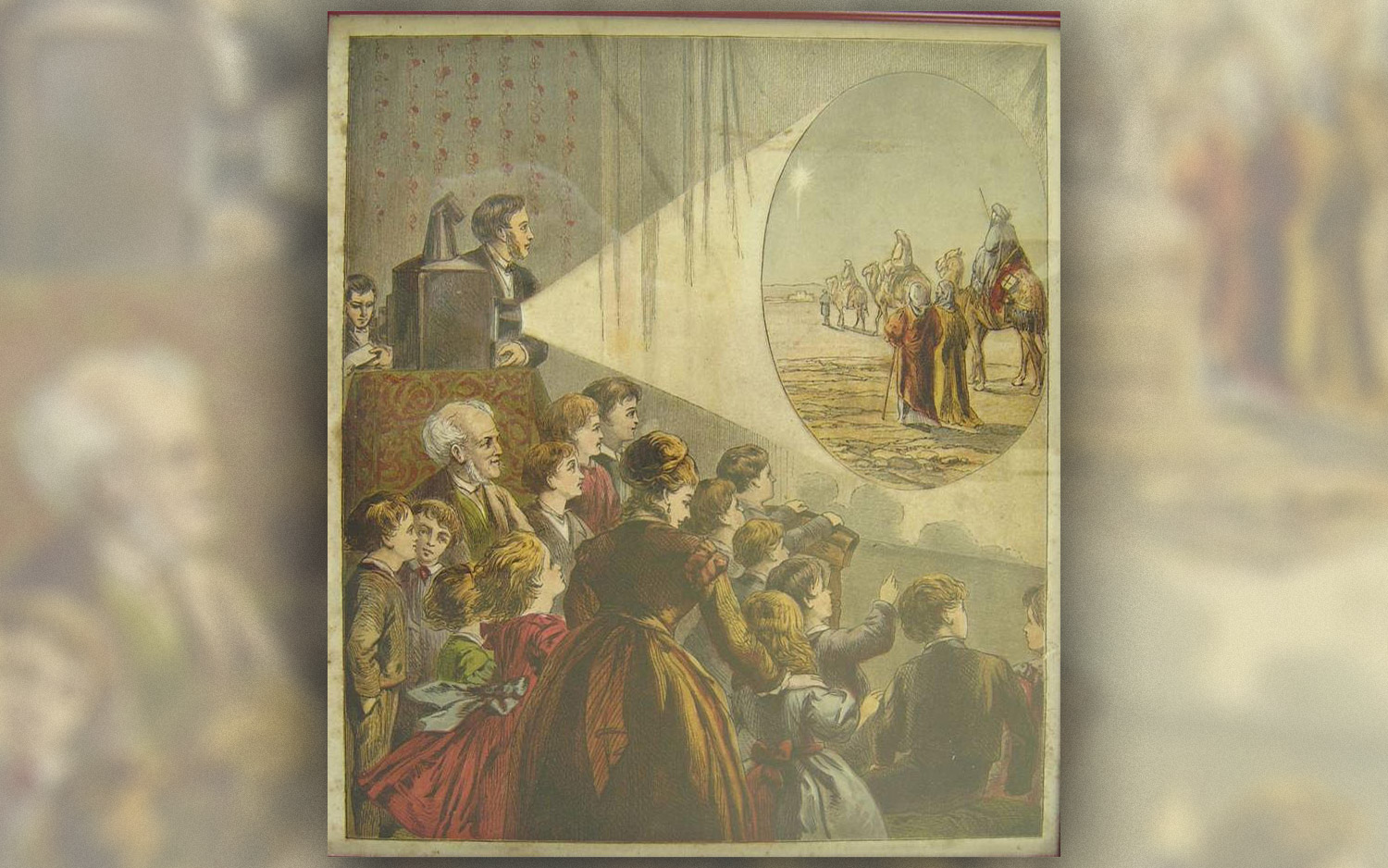

Netflix didn't exist during the Victorian era, of course, but people living during the 1800s and early 1900s had another way to binge-watch: the "magic lantern." According to new research, these early projectors were much more common and accessible than previously thought.

Magic lanterns — basically an early form of the slide projector — could show 3D and even moving images (much like today's GIFs) to entertain a captive audience. But given the lanterns' high price tag, modern historians long suspected that few but the wealthy could afford these projectors.

But new research finds that middle-class families regularly rented these machines, often for birthday parties, holidays and other social events. The research, which has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, was presented Aug. 29 at the British Association for Victorian Studies 2018 Annual Conference at the University of Exeter, in England. [19 of the World's Oldest Photos Reveal a Rare Side of History]

John Plunkett, an associate professor of English at the University of Exeter, made the finding by combing through newspapers from the Victorian era. He found a medley of magic-lantern advertisements, suggesting that people frequently hired lantern operators and rented slideshows they coulddisplay on magic lanterns, particularly around Christmastime and children's birthdays.

Magic lanterns were so popular that the Victorian equivalent of a video store existed so people could rent new slideshows to show at churches, town halls and homes, Plunkett told Live Science. These slideshows illustrated adaptations of novels, such as Charles Dickens' "A Christmas Carol," and photos from faraway lands, such as Egypt, Plunkett said.

"Just like Netflix or the many stores that hired [i.e., rented] out videos and PC games, this was a way of getting access to much more visual media than you could ever afford to buy," Plunkett said in a statement.

People first began using magic lanterns in the 1500s, but it wasn't until the early to mid-1800s that the technology became more widespread as opticians, photographers and stationers (people who sold stationary and office supplies) in England began renting out the devices, Plunkett said. In the 1850s, these businesses also began lending out stereoscopes — instruments used to see images in 3D, Plunkett said. Stereoscopes work just like a View-Master, by showing right-eye and left-eye views of the same scene so that they can be viewed together as a 3D image.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We know Victorian families were enthralled by magic lanterns and stereoscopes, and now we know this drove a thriving commercial practice of hiring [or renting out] lanterns and slides," Plunkett said. "This really was the Netflix of its time."

The earliest advertisement Plunkett unearthed was from an 1824 Morning Post newspaper, in which an optician from London's Oxford Street offered "The Magic Lantern sent out for an evening," Plunkett said.

In an 1843 advertisement, Thomas Bale, a watchmaker and optician in Bristol, advertised lanterns for rent with "astronomical, scriptural, natural history and comic slides." It was common for entrepreneurs, such as Bale, to offer shows with 100 slides, promising a night of entertainment, Plunkett said. Some shows were accompanied by music or lecturers, he added.

But setting up the magic lantern was challenging. Although the device initially used a candle to illuminate the slides, operators later opted for a stronger light made by burning the mineral lime with a mix of oxygen and hydrogen. In fact, that's where the phrase "in the limelight" comes from, Plunkett noted.

Igniting a fire with oxygen and hydrogen from separate gas bags often proved disastrous, and "there are quite a few reports of accidents or things exploding," Plunkett told Live Science. So, people often paid operators to set up the magic lantern in their homes, he said.

But these early PowerPoint-like shows weren't everyday events.

Renting a "lantern and slides was very much an expensive treat for the middle classes, especially if they wanted a lanternist, too," Plunkett said in the statement. "As the century went on, it became much more affordable."

As technology advanced, especially with the advent of moving pictures in the 1920s, magic lanterns became a forgotten technology. But for a few decades, they foreshadowed the popularity of DVDs and streaming video services like Netflix, showing that the Victorians were trendsetters, too.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.