Here's What Growing Inside Your Rubber Ducky

This will take the fun out of bath time: A new study finds that rubber ducky toys are teeming with bacteria and fungi.

In the study, the researchers analyzed the microbes growing inside 19 real bath toys, taken (with permission) from households where the toys had been well-loved. The scientists also set up some controlled experiments, in which they started with new bath toys and subjected them to various conditions. Some of these new bath toys were periodically placed into a bath with clean water, while others were placed in "dirty" water after a bath.

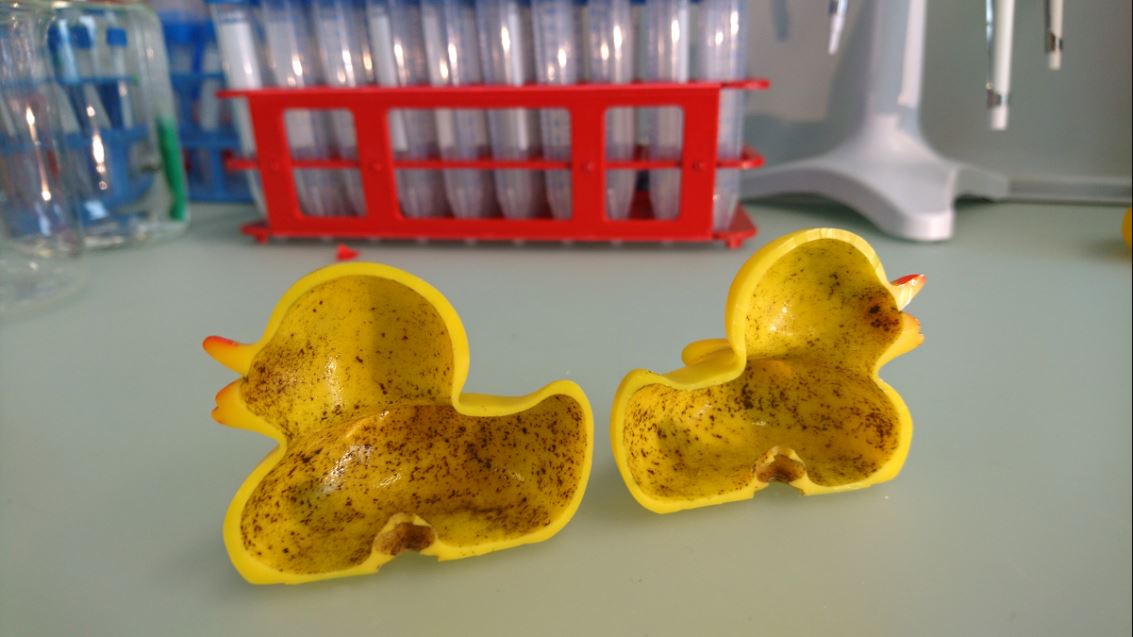

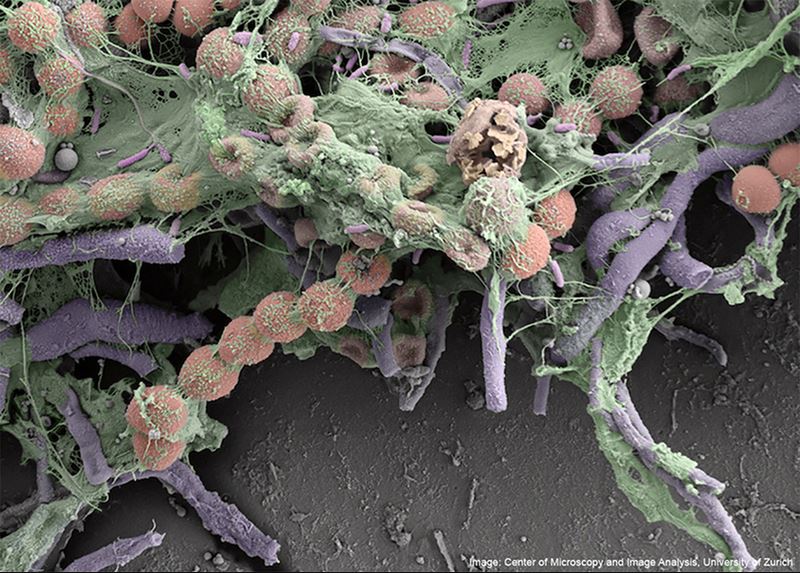

The results were pretty gross. Upon dissecting the bath toys, the researchers found "dense and slimy biofilms" on the objects' inner surfaces. The toys contained between 5 million and 75 million bacteria cells per square centimeter. [6 Superbugs to Watch Out For]

The researchers also found fungi species in 60 percent of the real bath toys and in all of the "dirty water" toys.

Exactly which bacteria or fungi appeared, and their abundance, tended to vary from household to household, the study said. But overall, the researchers found potentially harmful bacteria — including Legionella and Pseudomonas aeruginosa — on 80 percent of the toys studied.

"Moldy bath toys are widely discussed in online forums and blogs, but they have received little scientific attention to date," senior study author Frederik Hammes, of the Department Environmental Microbiology at the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, said in a statement. In fact, these toys are interesting for researchers, because they represent "the junction between potable water, plastic materials, external contamination and vulnerable end-users," meaning children, Hammes said.

However, whether the bacteria and fungi found on bath toys are harmful to children is unclear. Indeed, many researchers think that some level of exposure to bacteria and other microbes helps to build a healthy immune system in children.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But, with less-developed immune systems, children are also more vulnerable to certain infections. This means that "squeezing water with chunks of biofilm into their faces ... may result in eye, ear, wound or even gastrointestinal-tract infections," the researchers wrote in the study, which was published in the March issue of the journal Biofilms and Microbiomes.

But future studies are needed to examine the risk of contracting diseases from bath toys, the scientists said.

The researchers added that the plastic materials found in bath toys may play a role in the development of bacteria growth, because these "low-quality polymer" materials often release substantial amounts of organic carbon compounds, which can fuel the growth of microbes. In addition, human bodily fluids and bacteria that shed off our bodies into the water may also contribute to the biofilm growth on bath toys, the researchers said.

Ways to clean bath toys include boiling the toys or removing the water from them after use. But the researchers said that tighter regulations on the types of materials used to make bath toys could also be considered. Better materials that don't leach so many organic compounds could lower microbial growth on the toys, the researchers said.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.