Why One Woman Had Oil in Her Lung for Decades

An elderly woman in Florida had oil in her lungs — for decades — from a now-outdated procedure she received in her 20s to treat tuberculosis (TB), according to a new report of the woman's case.

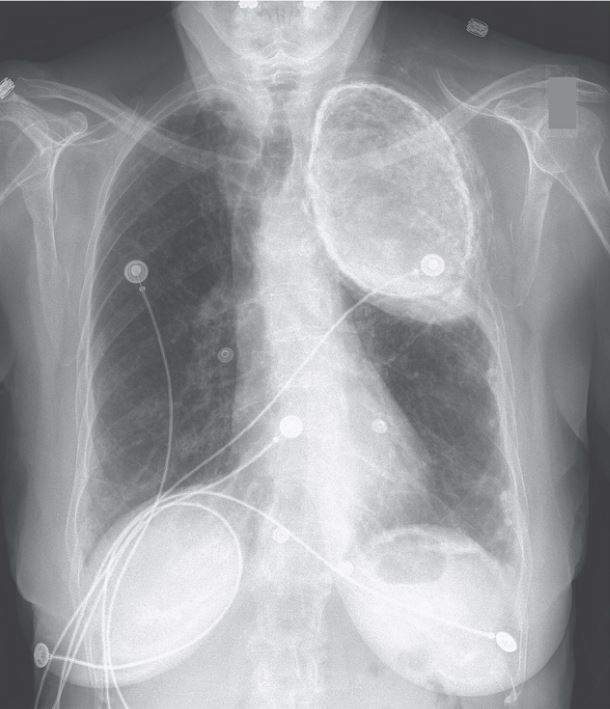

The 86-year-old woman went to the doctor because of a burning pain in her chest and upper stomach. She was diagnosed with acid reflux, and her symptoms got better after she started treatment for the condition. But while she was at the hospital, she received a chest X-ray that showed something unusual: There was an opaque, cloudy area in the upper part of her left lung.

This cloudy area was concerning to her doctors, because it could have meant that she had fluid buildup in the space between her chest wall and her lung, known as the pleural cavity. In people with certain conditions, blood or pus can accumulate in this area.

However, the woman remembered having oil injected into her lungs decades earlier, as a treatment for tuberculosis. This procedure was called oleothorax, and it was abandoned in the 1950s after effective antibiotics for TB were discovered, said Dr. Abhilash Koratala, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Florida, who treated the woman and co-authored the report of her case. [27 Oddest Medical Cases]

Given that more than 60 years have passed since this treatment was used, it's rare to see patients today with oil in their lungs from oleothorax, Koratala told Live Science. What's more, most patients who received the oil treatment eventually had the oil suctioned out of their lungs. But some patients never went back to the doctor to have the oil removed, because they were no longer experiencing symptoms from their tuberculosis, as was the case with this patient, the case report said.

The woman didn't give a specific reason for not getting the oil removed, but "it's not uncommon for patients to not go back to the doctor if they are feeling good," Koratala said.

The idea behind oleothorax was to use injections of oil, such as vegetable or mineral oil, to collapse the lung affected by TB bacteria, Koratala said. In the 1930s to 1950s, doctors thought that such "collapse therapy" would give part of the lung a chance to rest, and help kill TB bacteria, according to the Museum of Health Care at Kingston in Ontario, Canada.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When oil is injected into the pleural cavity, blood vessels and lymphatic vessels in the area initially absorb some of the oil, Koratala said. At the time the treatment was in use, doctors often had to "refill" this part of the lung with oil until it collapsed, he said. But over time, the membranes in the cavity would stop absorbing oil, probably because of damage to the tissue caused by the oil, Koratala said. This allowed the oil to remain in the pleural cavity, keeping the lung collapsed. After many years, some deposits of calcium would occur in the area, and the oil mass would stabilize, Koratala said.

The finding of oleothorax in this patient was accidental; it wasn't causing her any symptoms, and it wasn't related to her acid reflux, the doctors said.

Because the woman's condition was stable, there was no need to perform a procedure to take out the oil now, Koratala said. The risks of such a procedure would outweigh the benefits for this patient, and the calcification in the area would make it difficult to remove the oil, he said.

Although the upper part of the woman's lung remains collapsed by the oil, the rest of the lung is fine and can still function, Koratala said

But it's important for the woman and her doctors to be aware of the condition, because some patients experience complications from oleothorax, including infection or expansion of the area, which can cause breathing problems, Koratala said.

"We have to be aware of the complications of oleothorax so that we treat them in an appropriate and timely manner," Koratala said.

And even though this condition is rare, it's also important for doctors to keep it in mind, in order to avoid treating patients unnecessarily when they don't have symptoms, Koratala said. In some cases, doctors who have seen patients who underwent oleothorax have suspected that the patients had lung cancer, and preformed unnecessarily biopsies of the lung, he said.

The report was published March 23 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.