Oldest Indigo-Dyed Fabric Ever Is Discovered in Peru

The oldest indigo-dyed fabric ever found has been discovered in Peru, pushing back the use of this blue coloring to at least 6,200 years ago.

Previously, the oldest sample of blue-dyed fabric dated to around 4,400 years ago in Egypt, with the oldest written references to blue dye going back to around 5,000 years ago in the Middle East. The discovery in Peru, however, shines a spotlight on the Americas, which are less-discussed in terms of firsts, said study researcher Jeffrey Splitstoser, an archaeologist and textile expert at The George Washington University.

"The people of the Americas were making scientific and technological contributions as early and in this case even earlier than people were in other parts of the world," Splitstoser told Live Science. "We always leave them out. I think this finding just shows that that's a mistake." [Gallery: See Images of the Oldest Indigo]

Bundles of blue

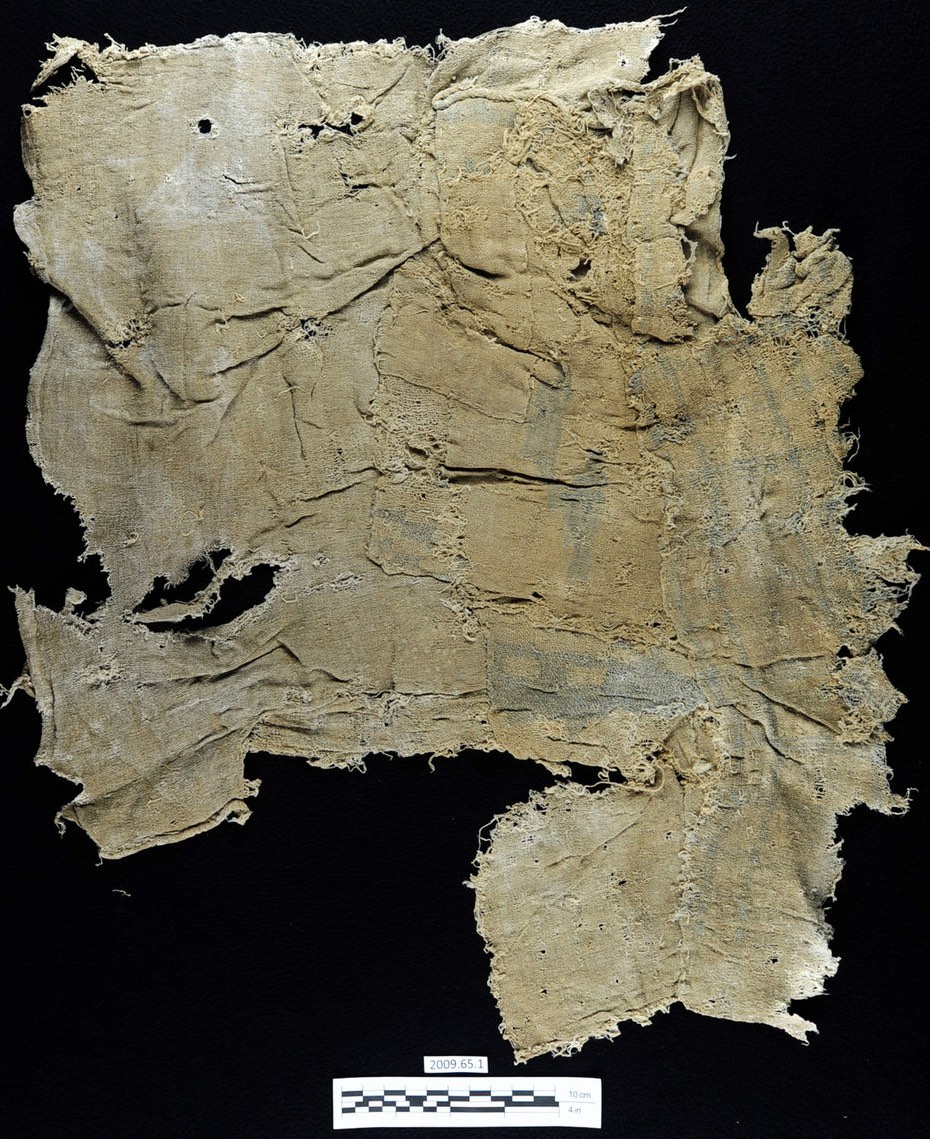

The dyed fabric pieces are small scraps made of woven cotton. They were excavated by archaeologists Tom Dillehay and Duccio Bonavia between 2007 and 2008 from a prehistoric site called Huaca Prieta, which is north of the city of Trujillo in coastal Peru. Huaca Prieta was a prehistoric dwelling that was covered by a mound and turned into a temple, Splitstoser said. The temple was made of a sort of concrete mixed from ash, shells and sand; over the years, many layers of this material had been applied to the structure as local people renovated and rebuilt the temple. The fabric scraps were found in bundles lining the ramp that led up to the top of the temple, embedded in the concrete-like layers. They all date to between 4,000 and 6,200 years ago.

"They were literally sealed under these new layers of building, but because the building material had so much ash in it, it leached into the textiles, making them a very dirty, sooty color," Splitstoser said.

The blue color didn't appear until conservationists washed the textiles. Almost all blue dye in nature comes from the compound indigoid, Splitstoser said, which can be made by many plants. But the first tests on the fabric yielded no sign of indigoid. Splitstoser was stumped.

He persevered, finding another chemist — Jan Wouters of University College London — with more sensitive equipment. Wouters, using a sensitive technique called high-performance liquid chromatography, was able to tease out the chemical makeup of the dye to discover that it was, in fact, indigo. He tested eight tiny samples of the blue cotton and confirmed indigo in five of them.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"That's when we realized then that we had the world's oldest indigo, by far," Splitstoser said.

Ritual fabrics

The fabric pieces were all cut or torn before they were deposited on the temple ramp, which probably represented a ritual "killing," by peoples who viewed objects as living, Splitstoser said.

"We see that all over the Andes. They not only ritually killed textiles, but they ritually killed ceramics. Anything that was buried was broken," he said. [Photos: Journey Into the Tropial Andes]

Some of the fabrics showed signs of being wetted and then squeezed out, possibly as part of the ritual, Splitstoser said. The fabrics weren't just blue — they were woven in patterns made of blue-dyed yarn, natural off-white cotton and bright-white thread made from milkweed, a very rare textile in South America, Splitstoser said. The yarn had also been dipped in red and yellow ochre, an iron pigment often used in rock art. Unlike the indigo, the ochre would have run when wetted.

"If you were to pour water on those and then squeeze it, you'd get colored water pouring out of the textiles, which might have been part of the show," Splitstoser said. No one knows what these rituals might have represented to the people who invented them; the era in which the textiles were made was one of a drying climate, Splitstoser said, so perhaps the rituals had to do with rain or water.

The discovery of indigo dye more than 6,000 years ago couldn't have been mere happenstance. Indigo dye is quite complicated to make, Splistoser said. Many dyes are made from flowers and require simply boiling the blossoms in water to extract the color, he said.

"Indigo does not work that way," he said. "If you put the leaves — and it's leaves, not flowers — in water, nothing will happen."

Instead, the leaves have to be fermented. Then, the fermented mixture must be aerated so that a solid compound falls out of the mixture to the bottom of the tub. This mixture can be taken, dried and stored. To reconstitute it requires an alkaline substance, often urine, which makes white indigo, a water-soluble compound. Yarn dipped in white indigo will turn yellow, green and finally blue, "like magic," Splitstoser said.

"This was probably a technology that was invented by women," he said, as women were typically in charge of weaving and dying in Andean cultures. A few of the later fabric scraps were of fine quality and more complex decoration, he said, but most of the scraps were likely simple squares or rectangles made by locals, who also wove fishing nets and fabric bags.

"They weren't primitive," Splitstoser said.

The researchers reported their findings today (Sept. 14) in the journal Science Advances.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus