Highest-Altitude Prehistoric Rock Art Revealed

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

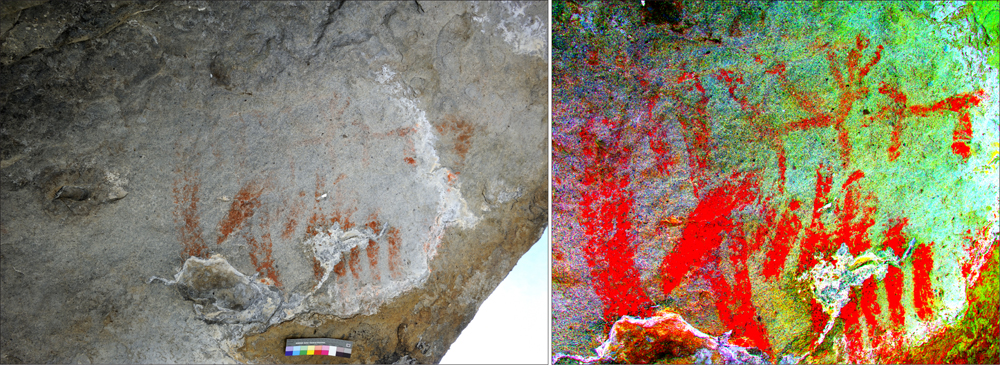

New digital scans reveal the highest-elevation prehistoric rock paintings ever discovered, in living color.

The scans were made in the Abri Faravel, a small rock overhang in the southern French Alps. In 2010, researchers found paintings decorating the ceiling of the rock shelter, consisting of parallel lines as well as what look like two animals facing each other. Excavations reveal signs of human activity starting in the Mesolithic (the period between about 10,000 B.C. and 5000 B.C.) and extending all the way into the Middle Ages.

To make the scans of the rock paintings, researchers rigged a contraption of car batteries and white lights, which were set up at nearly 7,000 feet (2,133 meters) above sea level. [Gallery: See Scans of the High-Elevation Rock Art]

"This is the only example of virtual models, including a scan of the art, done at high altitude in the Alps and probably the highest virtual model of an archaeological landscape in Europe," project leader Kevin Walsh, a senior lecturer in archeology at the University of York in England, said in a statement.

The researchers published the scans in the open-access journal Internet Archaeology. The virtual scans allow viewers to navigate through a 3D model of the high-elevation plateau where the rock shelter sits, and to zoom in on the rock art itself. Using the 3D model, users can see, for example, that the ceiling paintings are only visible once you step under the rock hanging, and not from the shelter's exterior.

Other archaeological finds around the plateau include Mesolithic flints, indicating that hunting took place in the area. At the time, the researchers wrote, the shelter would have been just below the tree line, at the edge of a forest where game periodically emerged. There is evidence that people farmed in the valleys below the plateau and hunted near the rock shelter during the Neolithic (5500 B.C. to 2800 B.C.). One Late Neolithic arrowhead was found well above the rock shelter at 8,202 feet (2,500 m).

In the Bronze Age, stone buildings were constructed around the plateau. These structures may have been animal pens or cheese-making huts used by early dairy farmers, the researchers wrote. Iron Age, hand-thrown pottery was found at the rock shelter, some dating to between 206 B.C. and 243 B.C. and some to between191 B.C. and 38 B.C. Between A.D. 315 and A.D. 420, someone arranged boulders into a semicircle and installed a pole at the entrance of the rock overhang, perhaps to support some sort of covering that would have extended the sheltered space.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

That shelter has been key to preserving the ancient art, Walsh and his colleagues noted.

"These paintings have survived for over two millennia, possibly four," they wrote. "Their fortuitous position, on the ceiling of an overhang, has afforded them natural protection — even during the winter, the snow seems to form as a wall in front of the rock shelter, leaving the area under the overhang open and free from direct exposure to the elements."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus