Whodunit? Mystery Lines Show Up in Satellite Image of Caspian Sea

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

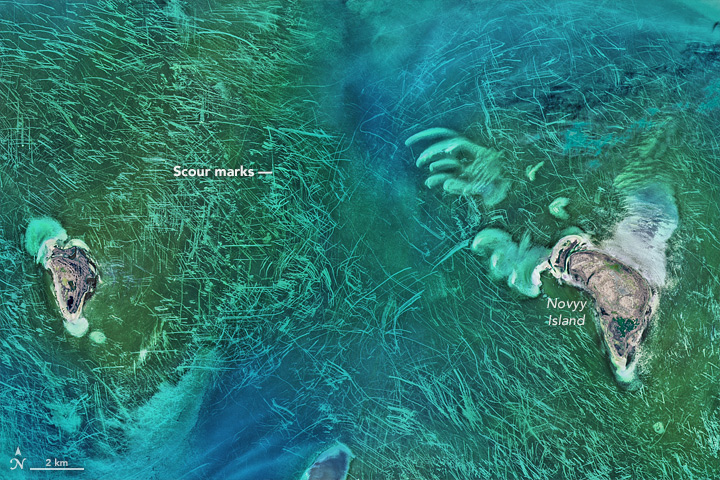

From 438 miles (705 kilometers) up, the floor of the north Caspian Sea looks like someone's just scoured it with a Brillo Pad. What could these bizarre marks be? Trawling scars? Propeller marks in sea algae or seagrass? An extraterrestrial message?

Don't get out the tinfoil hat yet: NASA scientists say these mystery lines are the work of sea ice.

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center ocean scientists noticed the image this month, shortly after it was acquired by the Operational Land Imager on the Landsat 8 satellite, according to NASA's Earth Observatory. The space agency put out the puzzler on Twitter, asking readers what the lines might be.

Now, the answer seems clear. Stanislav Ogorodov, an earth scientist at Lomonosov Moscow State University in Russi, told the Earth Observatory that the phenomenon was almost certainly all natural: "Undoubtedly, most of these tracks are the result of ice gouging," he said. [14 of the Strangest Sites on Google Earth]

The water in this area near Novyy Island is only about 10 feet (3 meters) deep, Ogorodov said, and the sea ice gets to be only about 1.6 feet (0.5 m) thick. But winds and currents sculpt this ice cover into jagged patterns called hummocks, which can reach the seabed. When wind or water pushes the floating ice around, Ogorodov explained to the Earth Observatory, the protruding parts can dig into the ocean floor and leave the scouring patterns seen from space.

Humans can cause similar-looking patterns. Propellers have scarred seagrass in the Everglades in Florida, and ships that fish by bottom trawling can bulldoze swaths of the seafloor with their nets. In the Caspian, though, the ice is almost certainly the predominant cause of these scours, according to the Earth Observatory. A look at a comparison image taken in January, when the ice was thick, shows chunks of ice at the ends of scour marks — the geoscience equivalent of a smoking gun.

The image also shows dark green coloration, which is likely seagrass or algae. The island in the image, Novyy Island, is the easternmost island of the Tyuleniy Archipelago, a group of islands in the northeastern part of the Caspian Sea that belong to Kazakhstan.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Caspian is the largest inland sea in the world, and is bordered by Iran, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Russia, Azerbaijan and Iran. The sea has no outflow to the ocean, and is, by an odd quirk of fate, below sea level. The northern end of the sea seen in the NASA image is in the Caspian Depression. The sea in this spot is about 92 feet (28 m) below sea level.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus