North American Mammoths Actually Evolved in Eurasia

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

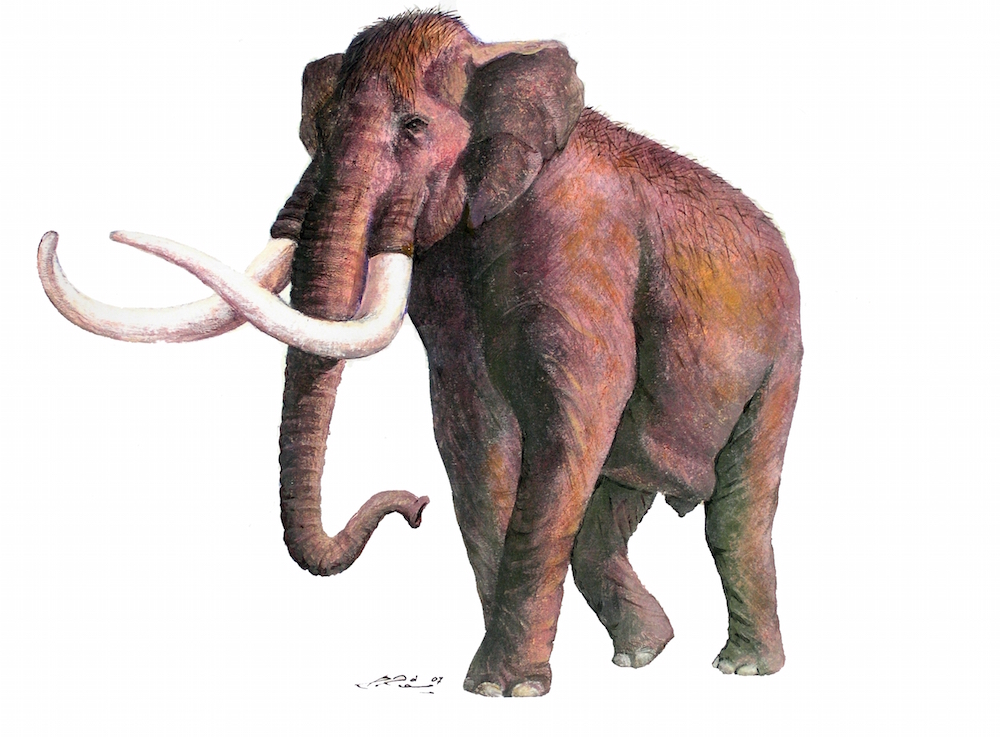

The famous Columbian mammoth — an 11-ton creature known for traversing North America during the last ice age — might actually be the same species as the Eurasian steppe mammoth, a new study finds.

The discovery suggests that the first mammoth to enter North America was the Eurasian steppe mammoth, and not its ancestor, a European creature called Mammuthus meridionalis. The two species differed greatly — the steppe mammoth had many more adaptations to living in cold weather.

The finding helps to rewrite the story of the evolution of the mammoth in North America, said study co-researcher Adrian Lister, a research leader of paleontology at the Natural History Museum in London. [Image Gallery: Stunning Mammoth Unearthed]

But to understand the latest development, it's important to explain the history of mammoth evolution, Lister said. Mammoths first emerged in Africa about 5 million years ago and moved into Europe about 3 million years ago, before spreading across Asia. When the mammoths first reached Eurasia, they were "still a forest-living, warm-climate kind of elephant species," Lister told Live Science. "And then, through about 2 [million] or 3 million years of evolution, they turned into the familiar woolly mammoth of the ice age."

However, earlier research suggests that one of these warm-climate mammoths, the European Mammuthus meridionalis, made the long trek across the Bering Strait land bridge about 1.5 million years ago. It was thought that once it reached North America, the behemoth gave rise to the famous Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi), which had a stomping ground that ranged from Canada to central Mexico, Lister said.

But there's only shaky evidence that this European mammoth lived in North America, he said. Researchers base much of their findings on mammoth teeth, as the rest of the skeleton isn't always preserved or discovered. Whenever an ambiguous — or less developed — mammoth tooth is found in North America, scientists typically assign it to the European mammoth species, Lister said.

But these teeth may simply look less developed because they are worn down from chewing, and were likely more complex in the mammoth's youth, Lister said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"When you look at these worn teeth, they look more primitive than they really are," he said. Most of the more complex teeth are attributed to the Columbian mammoth, but it's possible that these worn teeth belong to the Columbian, too, he said.

Fossil evidence

The fossil record seems to support this idea. There are no known fossils belonging to the European mammoth in northeast Siberia or Alaska, "suggesting that this temperate-adapted species never dispersed as far north as the Beringian transit route," the researchers wrote in the study.

But researchers found the remains of the steppe mammoth (Mammuthus trogontherii) in northeast China dating to 1.7 million years ago, and in northeast Siberia dating to 1.2 million to 0.8 million years ago, Lister said. This makes the steppe mammoth a good candidate for the 1.5-million-year-old crossing into North America, he added.

Moreover, after a recent trip in which he analyzed hundreds of mammoth specimens (mostly teeth) in museums across the United States, Lister came to the realization that the steppe and the Columbian mammoth are likely the same species. [Photos: A 40,000-Year-Old Mammoth Autopsy]

"When we compared these steppe mammoths from Asia with the American Columbian mammoth, we found that they were virtually identical," Lister said. "The new idea is that this advanced mammoth actually evolved in Siberia and just moved over to North America, where it's called the Columbian mammoth, but it's really more of the same thing."

He joked that because the Columbian mammoth was named in 1857, almost 30 years before the steppe mammoth was named in 1885, technically all of these mammoths should adopt the name Mammuthus columbi.

This is a very "embarrassing name" for European scientists, who are used to calling it Mammuthus trogontherii, Lister said, laughing. Only time will tell how long that change will take, he said.

The researchers also reported that the Eurasian woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) later followed the steppe/Columbian mammoth into North America, but lived farther north, in the colder areas of southern Canada and the northern continental United States. However, the Eurasian woolly mammoth's range overlapped with its relatives, likely leading to interbreeding that birthed hybrid species, including Mammuthus jeffersonii, Lister said.

The study presents a compelling case that the steppe/Columbian mammoth was the first to reach North America, said Daniel Fisher, a University of Michigan paleontologist who was not involved in the new study.

However, it's impossible to say whether the worn-down teeth belong to an earlier or more advanced species, simply because there are few identifying characteristics on them, Fisher said. "[But] I'm happy enough to take this as the best statement, the best call of what is probably going on," he said.

Lister co-authored the study with Andrei Sher, a paleontologist with the Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution in Moscow, who died in 2007 before the study's completion. The findings were published online today (Nov. 12) in the journal Science.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus