Cretaceous Fur Ball: Ancient Mammal With Spiky Hair Discovered

This article was updated at 3:52 p.m. EDT.

The fossilized remains of a furry critter that once roamed the Earth alongside dinosaurs suggests that mammals have been growing hair the same way for at least 125 million years.

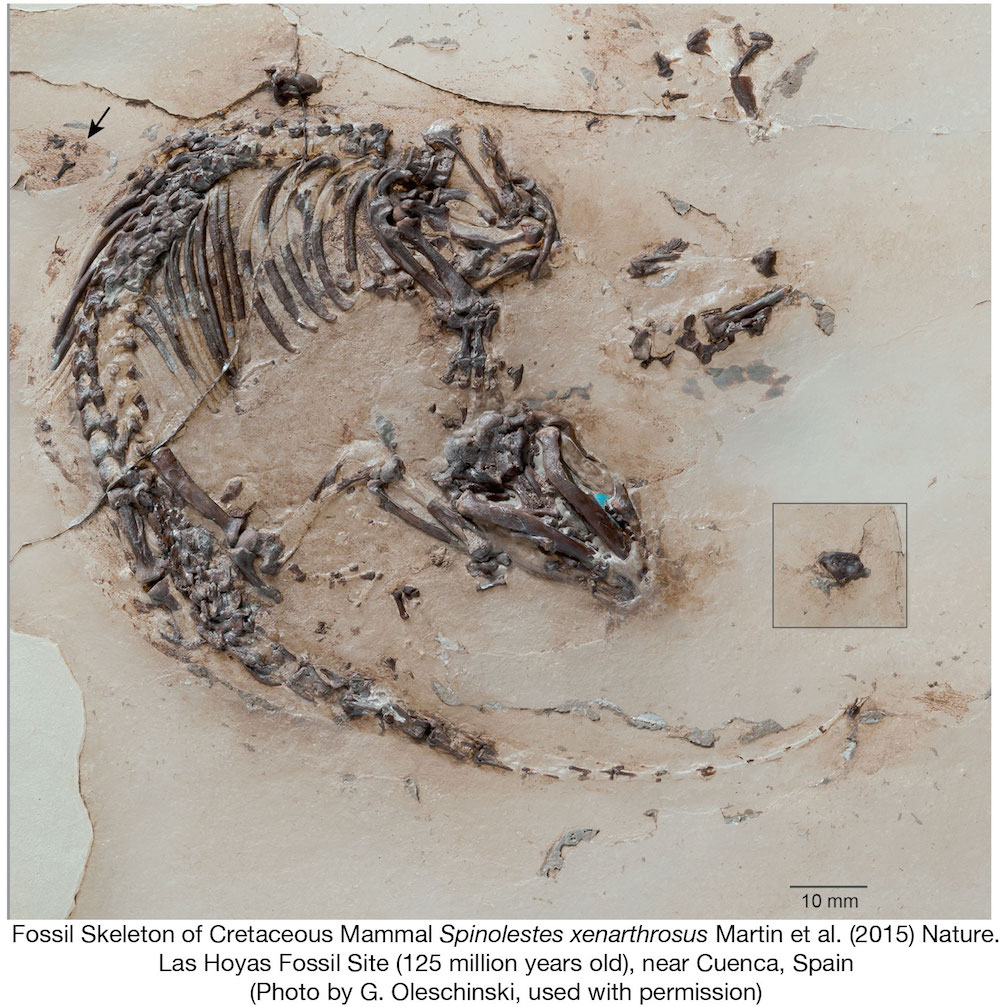

Discovered in 2011, the bones of the prehistoric mammal Spinolestes xenarthrosus are a "spectacular find," said Zhe-Xi Luo, a professor of organismal biology and anatomy at the University of Chicago and one of the authors of a new study about the hair-growing tendencies of this "Cretaceous fur ball."

The Spinolestes specimen is special because it was fossilized with so many of its parts intact, Luo told Live Science in an email. The animal's hair, dermal scutes (platelike structures made of skin keratin) and spines (similar to the spines of a hedgehog) are all preserved with "exquisite detail all the way down to the microscopic scales forming the hair shafts, the hair bulbs in the skin and microtubules that make up the spines," Luo said. [25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

And it's not just that the Spinolestesspecimen is well preserved — it's also really old. Before the fossil was unearthed by paleontologists in Spain, the oldest mammalian bones containing similar, hair-related microstructures dated back just 60 million years. The new discovery of Spinolestes pushes the fossil record further back by some 65 million years, into the Mesozoic era, proving that mammals have been hairy creatures for a really, really long time.

"Hairs are the most important feature of mammals," Luo said. Hair and the fat layer under the skin keep mammals warm, and the hair-related sweat glands keep warm-blooded creatures from overheating, he added.

The evolution of hair helped mammals survive environmental conditions that killed off hairless, cold-blooded dinosaurs about 66 million years ago, Luo and his fellow researchers said in their study, which was published today (Oct. 14) in the journal Nature. (Whether or not dinosaurs were cold-blooded like other reptiles is a decades-long mystery, with some research showing they were actually warm-blooded, and another recent study even suggesting the beasts were not warm- or cold-blooded but had a metabolism that was somewhere in between the two.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hairy history

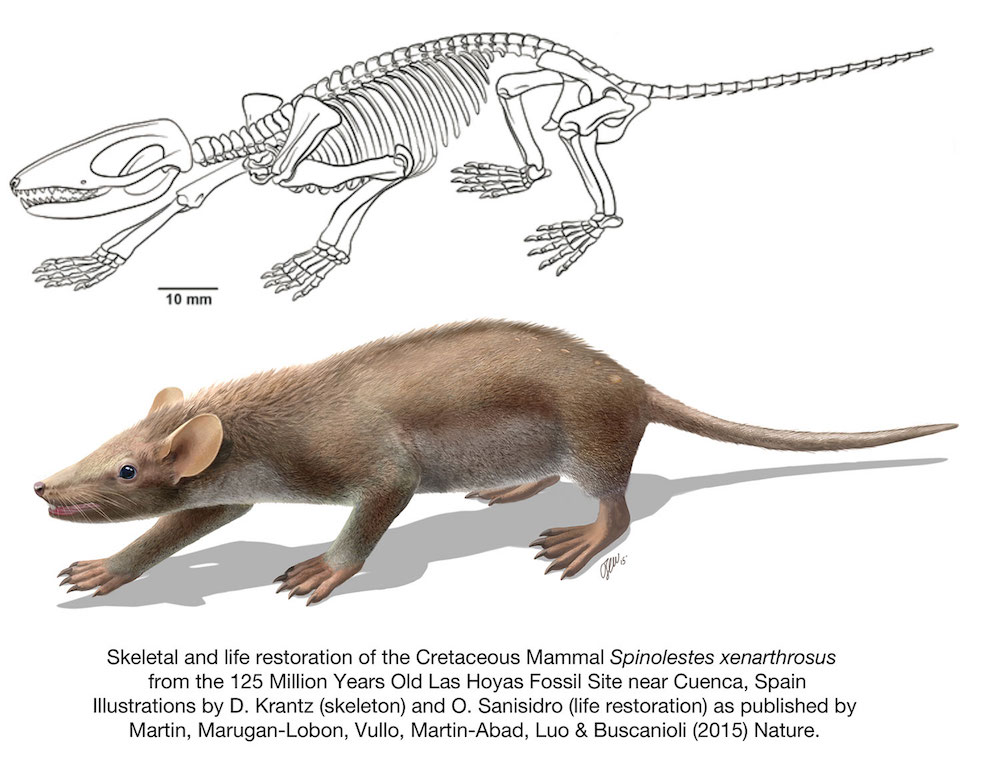

You may think that, over the course of 125 million years, the process by which mammalian hair grows would have changed somehow, but that's not the case, Luo said. The bones of Spinolestes, which was about the size of a small rat, are proof that ancient mammals grew hair the same way as modern mammals do.

Today's mammals grow a long hair, known as the "primary hair," out of a pore of the skin. Shorter, "secondary" hairs emerge from the same pore to surround the primary hairs. Collectively, these hairs are known as "compound hairs," and they develop this way because multiple hair follicles merge together during the growth process, Luo said.

Using a scanning electron microscope, the researchers looked at the hair follicles of Spinolestes and found that the ancient creature also had a bunch of compound follicles, each one sprouting a long primary hair surrounded by shorter secondary hairs. In other words, "the extinct Spinolestes actually grew its hairs the same way as modern mammals," Luo said.

In addition to its furry hide, Spinolestes had hedgehoglike spines on its back, which formed when small, hairlike structures called tubules merged together during the hair-growing process. This is the same way that modern-day hedgehogs and certain other mammals grow their spines, Luo added.

Because of the hairy similarities between this ancient mammal and modern mammals, it makes sense that Spinolestes would have experienced hair-related problems not unlike the ones that mammals face today. Luo and his colleagues found evidence that the prehistoric fur ball suffered from a fungal skin infection known as dermatophytosis, which results in abnormally truncated hairs. Modern mammals suffer from this affliction, as well.

The fossilized remains of the fur ball also held evidence of the animal's soft tissues. Iron-rich residues associated with the creature's kidney were preserved, as were microscopic bronchiole structures of the lung and an open body cavity that may have once held a muscular diaphragm used for respiration. These fossilized structures represent the earliest known record of mammal organs, the researchers said.

Spinolestes is the first-ever mammal fossil found at Las Hoyas Quarry in Spain. The researchers from the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid who discovered the ancient mammal have been digging up vertebrate fossils at the site since 1985. They have previously discovered prehistoric crocodiles, birds, fish and dinosaurs. The crustaceous fur ball was a rare find, one that Luo said he and other paleontologists studying early mammal evolution hope will be repeated again soon.

Editor's Note: This article was updated to clarify the debate surrounding whether dinosaurs are warm- or cold-blooded.

Follow Elizabeth Palermo @techEpalermo. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.