'Magnetic' Discovery May Reveal Why Earth Supports Life and Mars Doesn't

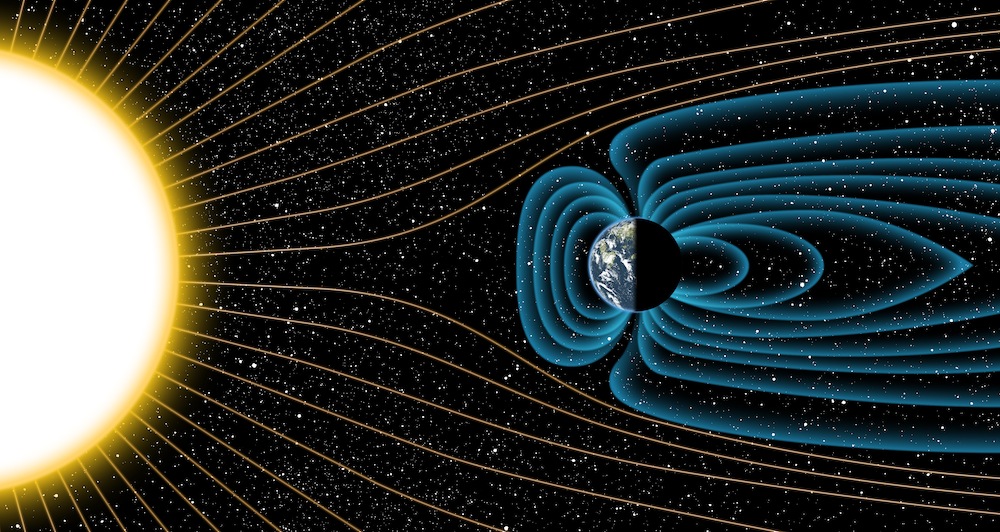

Earth's magnetic field, which protects the planet from harmful blasts of solar radiation, is much older than scientists had previously thought, researchers say. In fact, this invisible, protective shield likely existed shortly after the planet formed — a finding that could shed light on why Earth is habitable and Mars is not.

Without Earth's magnetic field, solar winds — streams of electrically charged particles that flow from the sun — would strip away the planet's atmosphere and oceans. As such, Earth's magnetic field helped to make life on the planet possible, researchers have said.

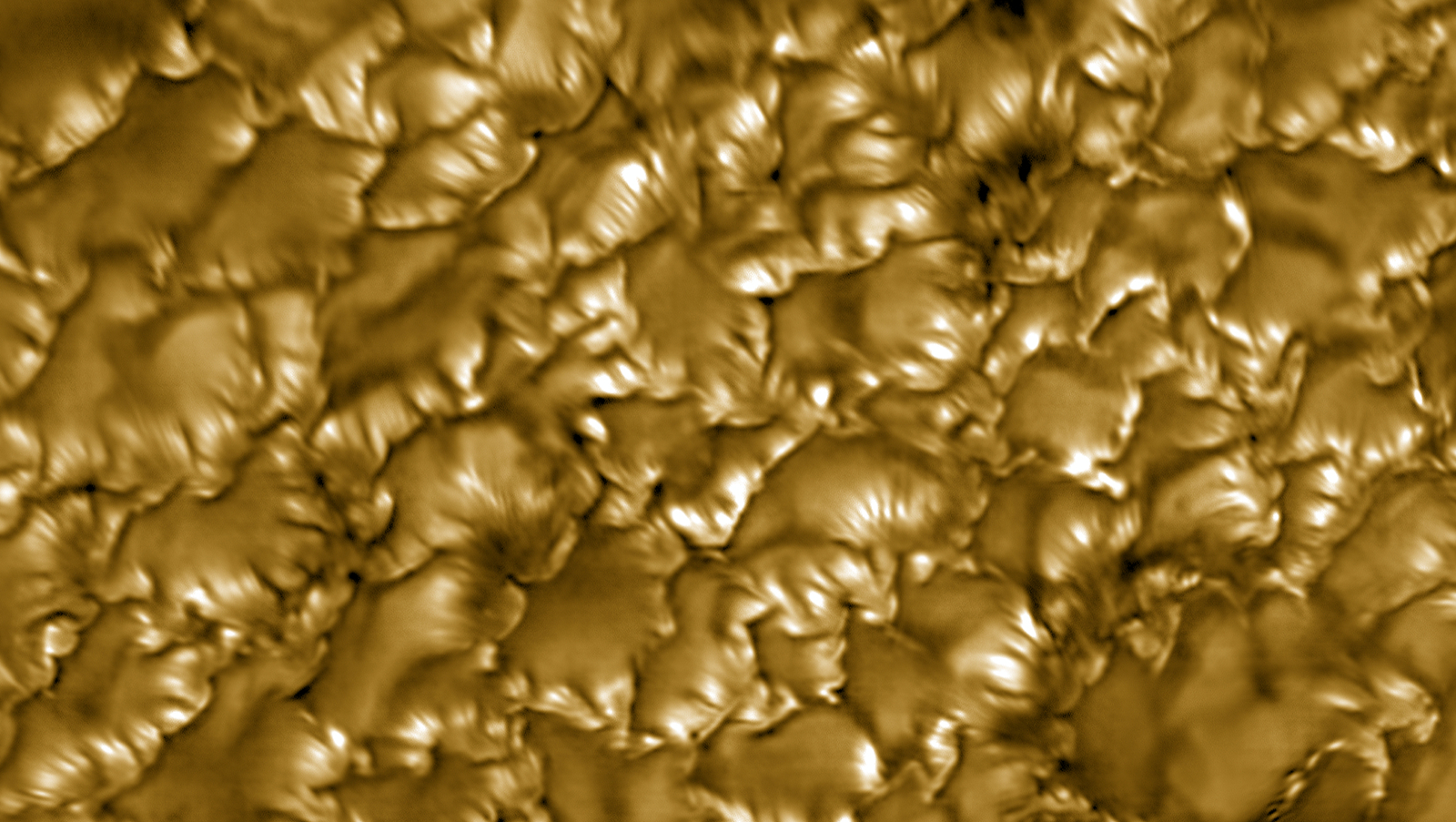

The magnetic field is generated by swirling liquid metal in Earth's outer core, and this "geodynamo" requires the release of heat from the planet to drive its churning. Nowadays, this heat flow is aided by plate tectonics — the movement of the plates of rock that make up the planet's exterior — which efficiently lets heat transfer from Earth's interior to its surface. [50 Amazing Facts About Planet Earth]

Given the importance of Earth's magnetic field, scientists want to pinpoint when it first developed, which could, in turn, provide clues about how the planet has been able to remain habitable and when plate tectonics began. However, when, exactly, plate tectonics originated is hotly debated, and some researchers argue that the early Earth lacked a magnetic field.

Since 2010, the best estimate of the age of Earth's magnetic field was 3.45 billion years. In comparison, Earth is about 4.6 billion years old.

Now, scientists have found that Earth's magnetic field could be up to 4.2 billion years old — about 750 million years older than had been previously thought.

The researchers investigated magnetically sensitive minerals such as magnetite, a naturally occurring cousin of rust. As molten rock cools, magnetite within it becomes literally set in stone, pointing to the location of Earth's magnetic poles at the moment it froze. As a result, the oldest samples of magnetite can reveal the direction and intensity of Earth's magnetic field at the earliest parts of Earth's history, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The scientists analyzed magnetite samples trapped in tiny, ancient zircon crystals that were collected from the Jack Hills in Western Australia. To detect the magnetic fields, the scientists had to have a special magnetic sensor built that was 10 times more sensitive than other instruments used to make these kinds of measurements.

Isolating the zircons from the surrounding rock was challenging. "Typically, we separate zircons out using high magnetic fields, but we couldn't do that here, since it would destroy what information they had," said John Tarduno, a geophysicist at the University of Rochester in New York and lead author of the new study detailing the findings. "So we had to separate thousands of zircons out by hand, cleaning them in mild acids, which took a huge amount of time," Tarduno told Live Science.

Then, to get reliable measurements, the researchers had to make sure the samples they analyzed never got hot enough after they formed to allow the magnetic information recorded within to reset. The researchers found that the minerals were pointed in a variety of magnetic directions, which suggested the samples were pristine.

"[I]f the magnetic information in the zircons had been erased and re-recorded, the magnetic directions would have all been identical," Tarduno said in a statement.

The intensity of the magnetic fields that the samples recorded suggests the presence of an ancient geodynamo, the researchers said.

These findings likely indicate that Earth had a magnetic field, and plate tectonics, since very early in its history.

"It's surprising, because some of the models of the ancient Earth suggest that a magnetic field or plate tectonics could not have occurred that early," Tarduno said. "Those models need to be rethought to include potential ways of cooling Earth's interior early on."

This ancient magnetic field could be a key reason Earth is still habitable and Mars was unable to sustain life, as far as we currently know.

"The oldest previously known magnetic field from a terrestrial planet was on Mars, which was older than 4 billion years old," Tarduno said. "But then, sometime after 4 billion years ago, it died off. If you compare the evolution of Earth and Mars, Mars had a more dense atmosphere, and water, but it probably lost both to erosion from the solar wind because it didn't have a magnetic field to protect them, whereas Earth always appeared to have had a strong magnetic shield."

The scientists detailed their findings in the July 31 issue of the journal Science.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.