Iridescent Pools Discovered in Undersea Volcano's Crater

Deep in the Aegean Sea, shimmering pools of white water meander through the caldera of the Santorini volcano.

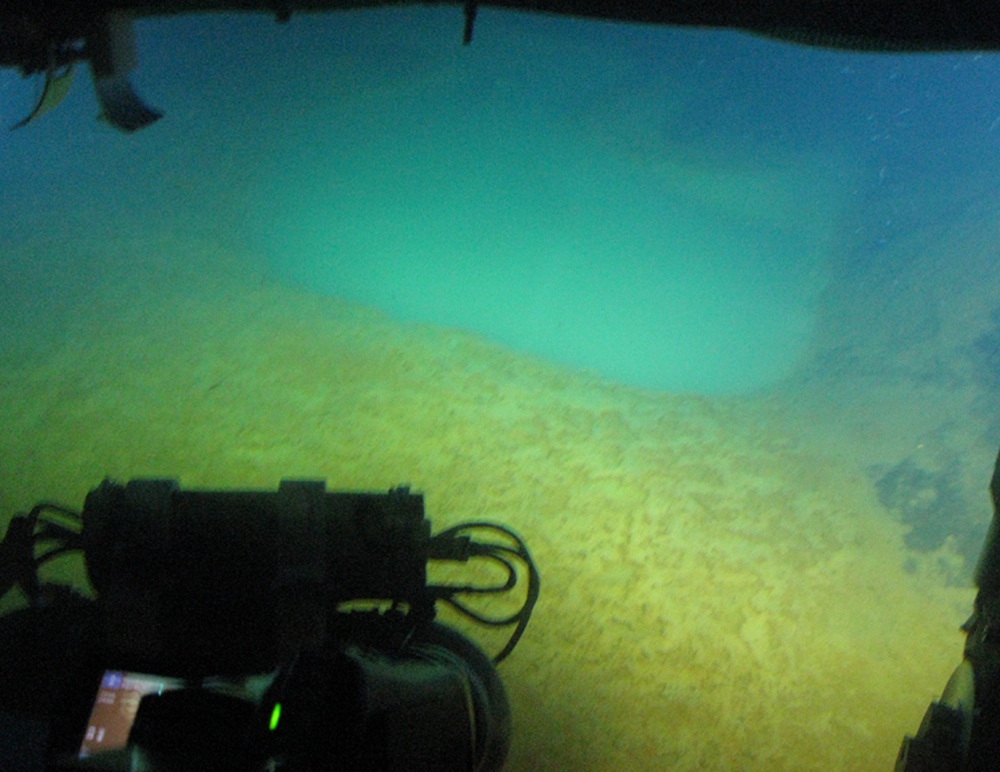

Never seen before, these opalescent pools — called Kallisti Limnes, from ancient Greek for "most beautiful lakes" — appear in a new video taken by underwater vehicles in July 2012. They contain high levels of carbon dioxide, which may make the water dense and prone to pooling.

"What we have here is like a 'black and tan' — think Guinness and Bass [Ale] — where the two fluids actually remain separate," said Rich Camilli, a scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and the lead author of a study on the phenomenon published July 16 in the journal Scientific Reports. (A black and tan is a layered drink made by mixing light and dark beers.)

"The volcanic eruption at Santorini in 1600 B.C. wiped out the Minoan civilization living along the Aegean Sea," Camilli said in a statement. "Now these never-before-seen pools in the volcano's crater may help our civilization answer important questions about how carbon dioxide behaves in the ocean." [See Photos of the Iridescent Pools in the Aegean Sea]

The picturesque Greek island of Santorini, or Thira, is actually the edge of an enormous caldera left behind after the eruption. Within this caldera are spots of hydrothermal activity. It was these spots that Camilli and his colleagues were investigating in 2012, a year after the caldera showed signs of increasing volcanic activity. (The unrest has since calmed.)

Using two autonomous underwater vehicles, the researchers explored the chemistry of the water in the caldera. They discovered the milky carbon dioxide-rich pools in depressions along the caldera wall.

The water in the ocean is not an undifferentiated mass — in fact, researchers have previously observed brine pools that separate out from surrounding ocean water because of extra-high salt content, Camilli said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"In this case, the pools' increased density isn't driven by salt," Camilli said. "We believe it may be the CO2 itself that makes the water denser and causes it to pool."

The observation is intriguing, because carbon dioxide was thought to diffuse through the ocean after being released from geologic activity. Underground carbon dioxide can come from magma or from limestone or other sedimentary rocks under tremendous pressure.

Because of the carbon dioxide, the pools were high in acidity. They may, however, host silica-based organisms, whose glassy microscopic bodies could explain the opal hue, the researchers reported.

The findings could help researchers understand how undersea calderas behave. They might also have implications for carbon capture and storage, one potential way to ameliorate climate change. Some scientists have suggested capturing carbon and trapping it under the seafloor in order to keep it out of the atmosphere (and out of the ocean, where its acidifying properties make it a danger to sea life). But little is known about how subsurface carbon dioxide behaves, or what might happen if the carbon leaks out of the ground.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus