Sweet! Deep-Space Sugars May Reveal Clues About Origins of Life

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Sugars may form in the types of ice found in deep space — a finding that could help to explain how comets and meteorites could have seeded the primordial Earth with key ingredients for life, researchers say.

In the dense molecular clouds from which stars and planetary systems are born, ices are, by far, the most abundant solids. Prior research had found that cosmic rays and ultraviolet radiation can help convert the chemicals that make up the bulk of these interstellar ices into complex organic matter, such as the precursors of proteins and fats.

"Ices are abundant in the interstellar medium, and it is unavoidable that some of them will receive energy from ultraviolet photons or cosmic rays, leading to molecular complexification," study co-author Louis Le Sergeant d'Hendecourt, an astrophysicist at the Space Astrophysics Institute in Orsay, France, told Space.com. [5 Bold Claims of Alien Life]

Now, scientists have detected sugars in experiments that mimic the way interstellar ices can evolve over time. Sugars are more than just sweet nutrients; they serve as the backbones of nucleotides, which, in turn, serve as the building blocks of the nucleic acids that make up DNA and its cousin RNA.

"DNA is the genetic source code for all known living organisms,"study co-author Uwe Meierhenrich, a chemist at the University of Nice Sophia Antipolis in France, told Space.com.

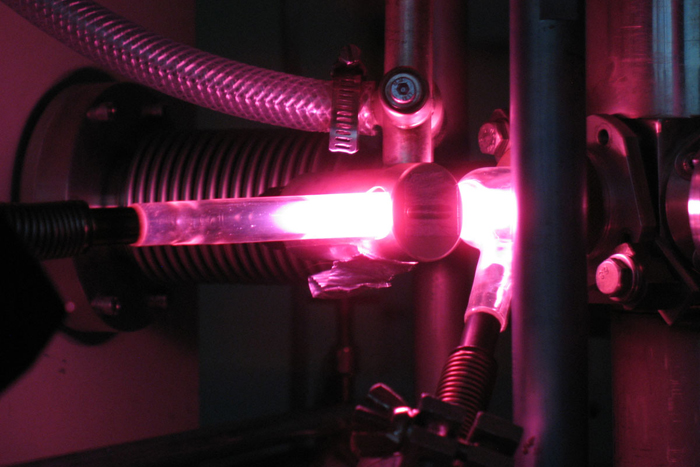

In the experiments, scientists created thin films made up of frozen water, methanol and ammonia in a vacuum chamber kept at minus 319 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 195 degrees Celsius). They irradiated these ices with ultraviolet rays to mimic how such material would evolve over time in interstellar space. Then, they slowly warmed the samples to room temperature and analyzed them.

In a first-of-its-kind discovery, the researchers detected compounds known as aldehydes. Most sugars derive from these compounds; the simplest and best-known example of an aldehyde is formaldehyde.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Among the 10 aldehydes the scientists detected were two sugar-related compounds, glycolaldehyde and glyceraldehyde — key precursors of nucleic acids, the building blocks of genetic material.

"Glyceraldehyde is a molecule of outstanding importance," Meierhenrich said.

The researchers cautioned that their experiments did not create life, but rather only the key building blocks for life. Still, they said these findings may help reveal how ancient comets and meteorites might have seeded a lifeless Earth and other planets with the chemistry needed for life to evolve.

Future research into interstellar ices can explore the mystery of why the compounds that make up life on Earth usually come in one form but not the other, the researchers said. Many organic molecules can come in two different forms that are mirror images of each other, like left and right hands. DNA on Earth is usually "right-handed," not "left-handed," because the sugar that makes up DNA's backbone is "right-handed." In the future, the scientists would like to investigate whether sugars in interstellar ices might also be either left-handed or right-handed.

The scientists detailed their findings online today (Jan. 12) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus