No Single Missing Link Between Birds and Dinosaurs, Study Finds

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

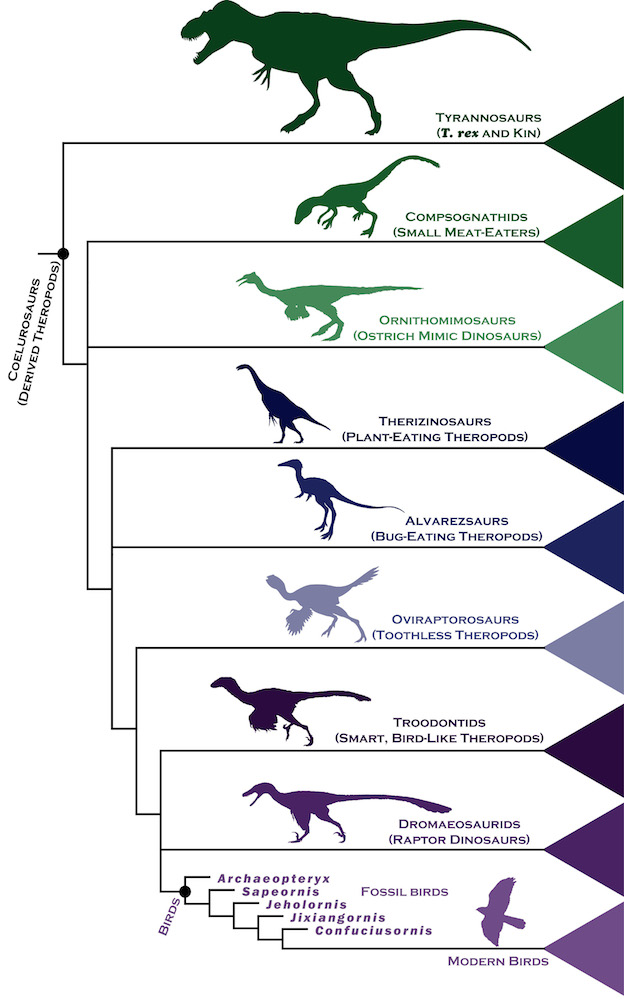

Birds didn't evolve in one fell swoop from their dinosaur ancestors, suggests a newly constructed dinosaur family tree showing our feathery friends evolved very gradually, at first.

The new pedigree of carnivorous dinosaur evolution is the most comprehensive one ever assembled, the researchers say. The findings show that birdlike features such as wings and feathers developed slowly over tens of millions of years.

But once the bird body plan was complete, the group underwent a burst of evolution that produced thousands of species, according to the study published today (Sept. 25) in the journal Current Biology. [Avian Ancestors: Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly (Images)]

"It's basically impossible to draw a line on the tree between dinosaurs and birds," said study co-author Steve Brusatte, a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh, in Scotland. But after the bird body arose, "something was unlocked, and [birds] began to evolve at a supercharged rate," Brusatte told Live Science.

Scientists have long known that birds are part of the dinosaur lineage. But because the fossil record has many gaps, some scientists and members of the public thought that a "missing link" must exist between the first bird and its closest dino ancestor. But more and more feathered dinosaur fossils have been cropping up over the past two decades, particularly in China, suggesting the development of birds was more piecemeal.

Brusatte and his colleagues examined more than 850 body features in 150 extinct species of birds and their closest dinosaur relatives. By analyzing the data using statistics, the researchers constructed a complete family tree.

The tree reveals that the characteristic features of birds evolved very gradually about 150 million years ago, and the earliest birds would have been indistinguishable from their closest relatives.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The label of "bird" is somewhat arbitrary, but scientists consider the feathered fossil Archaeopteryx to be the first of the group, Brusatte said. "What probably distinguishes birds is the ability to have powered flight," he said, though it's possible that other dinosaurs could fly too.

"Dinosaurs became ever more 'birdy' over time," Brusatte said, but there was no single missing link, he added. Birds and dinosaurs are like two colors in a rainbow, he said — you can recognize each, but they bleed into each other at their borders.

Yet once the basic body plan was established, the findings show, birds began to evolve much faster than other dinosaur groups.

"It is particularly cool that it is evidence from the fossil record that shows how an oddball offshoot of the dinosaurs paved the way for the spectacular variety of bird species we see today," Graeme Lloyd, another co-author of the study and a paleontologist at the University of Oxford, in England, said in a statement.

The findings provide support for the controversial idea that extreme bursts of evolution usually follow the origin of new body plan, first hypothesized by American paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson in the 1940s.

The researchers don't know what about birds made them so successful. Perhaps because birds are small, warm-blooded and move fast, they were able to persist while non-avian dinosaurs died out, Brusatte said.

But the researchers really don't know why avians outperformed their comrades. You might as well ask why Homo sapiens were so successful, compared with other human relatives, Brusatte said.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus