Early Flood Prediction Gets a Boost from Space

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Researchers have figured out a new way to predict which rivers are most at risk of dangerous flooding.

To do so, they measured how much water was stored in a river basin months ahead of the spring flood season.

"Just like a bucket can only hold so much water, the same concept applies to river basins," said lead study author J.T. Reager, an earth scientist at the University of California, Irvine. When the ground is saturated, or filled to its brim, conditions are ripe for flooding. [Top 10 Deadliest Natural Disasters in History]

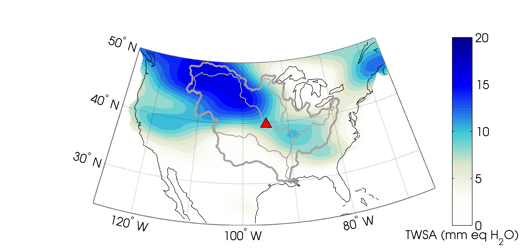

Reager and his colleagues looked back in time using satellite data, and measured how much water was soaking the ground before the 2011 Missouri River floods. The researchers found their statistical model strongly predicted this major flood event five months in advance. With less reliability, the prediction could be extended to 11 months in advance, the researchers said.

"This gives the background on what's on the ground before the rain even gets there," Reager said.

The findings were published today (July 6) in the journal Nature Geoscience.

The 2011 Missouri River floods lasted for months, closing interstates, shutting down nuclear plants and scouring farmland. The National Weather Service issued flood alerts in April, a month before flooding began.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Reager hopes his new method will eventually help forecasters prepare reliable flood warnings several months earlier. "It would be amazing if this could have a positive effect and potentially save lives," he said.

The researchers relied on NASA's twin GRACE satellites to diagnose a region's flood potential. As the satellites circle the Earth, changes in gravity slightly perturb their orbit. These tugs are proportional to changes in mass, such as a buildup of water and snow. (GRACE was originally designed to track melting in the ice sheets.)

The team used GRACE to look at all potential water sources, including snow, surface water, soil moisture and groundwater. "This gives us a more accurate interpretation of what's happening on the ground," Reager said.

So far, the method has only been tested when the team looked back at past floods. And it only works with certain types of floods — it can't help predict flash floods caused by sudden rains, such as India's monsoonal flooding, Reager said. "GRACE can only see this slow saturation flooding," he said.

There's also a three-month lag before the researchers can obtain data from the GRACE satellites, which means potential flood predictions using this method are limited to only two or three months in advance, Reager said. That's about the same amount of advance warning that on-the-ground measurements currently provide. NASA is, however, working on ways to speed up its data delivery to 15 days, he said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus