You've Got Smell: 1st 'Scent Message' Sent from NYC to Paris

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

NEW YORK — The first transatlantic "scent messages" were exchanged today (June 17) between New York City and Paris, and they smelled like champagne and macaroons.

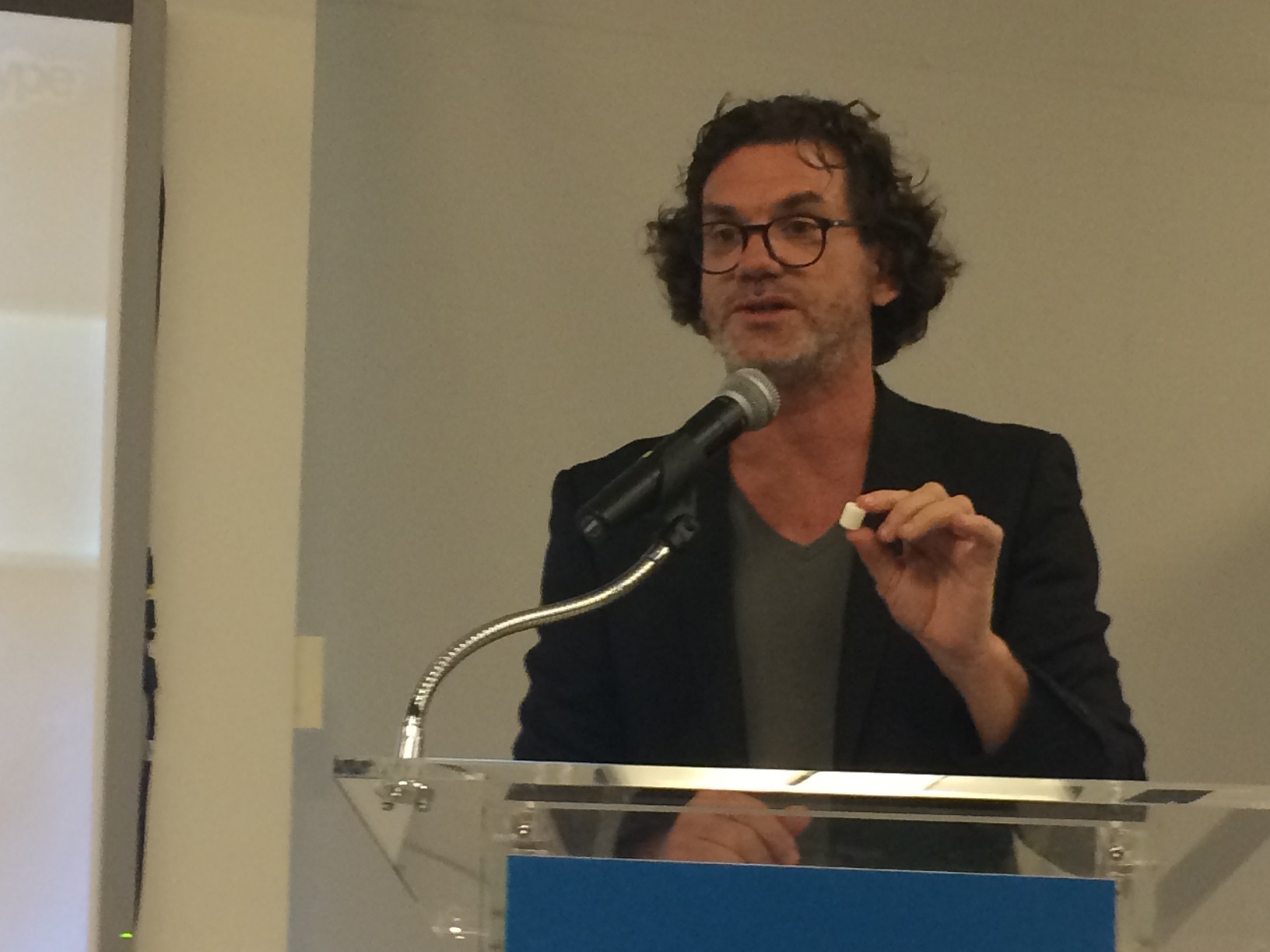

At the American Museum of Natural History here in Manhattan, co-inventors David Edwards, a Harvard professor, and Rachel Field showcased their novel scent-messaging platform, which involves tagging photographs with scents selected from a palette of aromas, and sending them via email or social networks. The messages are then played back on a new device called an oPhone.

From Paris, collaborators Christophe Laudamiel and Blake Armstrong joined the New York audience via Skype, and emailed a scent-tagged photograph of French delicacies and champagne they had just poured to celebrate the launch of the oPhone. When the oPhone on the New York side picked up the message, the device dissipated a subtle aroma that matched perfectly with the picture. [Hold Your Nose: 7 Foul Flowers]

"OPhone introduces a new kind of sensory experience into mobile messaging, a form of communication that until now has remained consigned to our immediate local experience of the world," Edwards, who is also the CEO of Vapor Communications, the company behind the scent-messaging platform, said. "With the oPhone, people will be able to share with anyone, anywhere, not just words, images and sounds, but sensory experience itself."

How it works

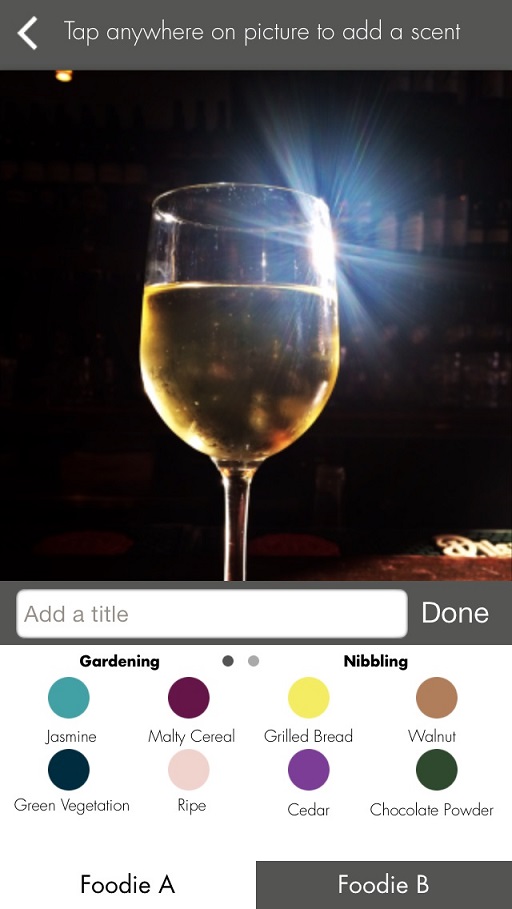

The scent messages, called oNotes, are composed in an iPhone app called oSnap, which also launched today. Using oSnap, users can mix and match from 32 primitive aromas to produce more than 300,000 unique scents, Edwards said.

The 32 aromas are placed inside oPhone's eight "oChips," which could be thought of as a printer's ink cartridges. When the device receives an oNote, it releases the corresponding aroma based on the aromatic tags assigned to the image.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Each scent is designed to last roughly 10 seconds, about the same time that people take to sense an aroma, Edwards told reporters in a news briefing today at the American Museum of Natural History. If the photo is tagged with more than one scent, the smells will play one after the other.

A virtual world of aromas

The idea of sharing scents started two years ago in Edwards' course at Harvard, a class called "How to Create Things and Have Them Matter." Field, then a mechanical engineering undergrad, and some of her classmates planned to create a virtual world of aroma. They further developed the idea at Le Laboratoire, Edwards' creative hub in Paris known for conducting experiments at the intersection of science and art.

Edwards' previous projects are no less imaginative. The engineer has designed air-purifying plants, edible bottles and vaccine technologies to deliver drugs to the lungs to eliminate injections, among other inventions.

In the scent-messaging project, Edwards is focusing on the food space, at least for now. The oPhones will be displayed in cafes in Paris in the coming days, and the idea is to test the devices' business potential at places where aromas matter, Edwards said.

oNotes are transmitted via email or social media, and can be picked up at hotspots where there are oPhones in place to receive them. The oPhones are available to preorder for $149 as part of the company's Indiegogo campaign, which started today. The American Museum of Natural History will host the first U.S. hotspot during three weekends in July, where people can try the oPhones and participate in educational activities demonstrating how humans process smell.

Human noses may be able to discriminate between as many as a trillion different odors. However, the olfactory ability has changed over time, making it an important subject in the study of the evolution of species. Throughout the last 55 million years of evolution, primates have lost their sharp sense of smell in a trade-off for better vision, according to current theories.

"We know, based on fossils and reconstruction of the brain on those fossils, that the olfactory system was far more developed than visual and auditory systems in the early stages of the mammalian evolution," said Michael Novacek, the American Museum of Natural History's senior vice president and provost for science. "So in a sense, our whole legacy really comes from the olfactory system, and its modifications and refinement, not just the vision and auditory systems."

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow us @LiveScience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus