Million-Year-Old Fossils Show Hippos Going for a Swim

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

More than a million years ago, hippopotamuses paddled across a shallow pool in the region that's now northern Kenya, occasionally scraping their feet on the sandy bottom. Today, researchers have evidence of the hippos' fleeting swim in the form of fossilized footprints.

The newly identified prints represent the first known tracks of ancient mammals taking a dip, joining previously discovered trace fossils left behind by swimming dinosaurs, turtles and crocodiles, the researchers said.

The hippo foot impressions were found in Kenya's Koobi Fora region, which is part of the Lake Turkana Basin, considered the cradle of human evolution because the area contains some of the oldest fossils from hominins — a group that comprises multiple species that came after Homo, the human lineage, split from chimpanzees. In fact, early humans may have witnessed the aquatic adventures of these ancient hippos; hominin footprints were discovered on the same geologic surface a mere 230 feet (70 meters) from the hippo tracks. [See Images of the Hippo Tracks]

'Bottom walkers'

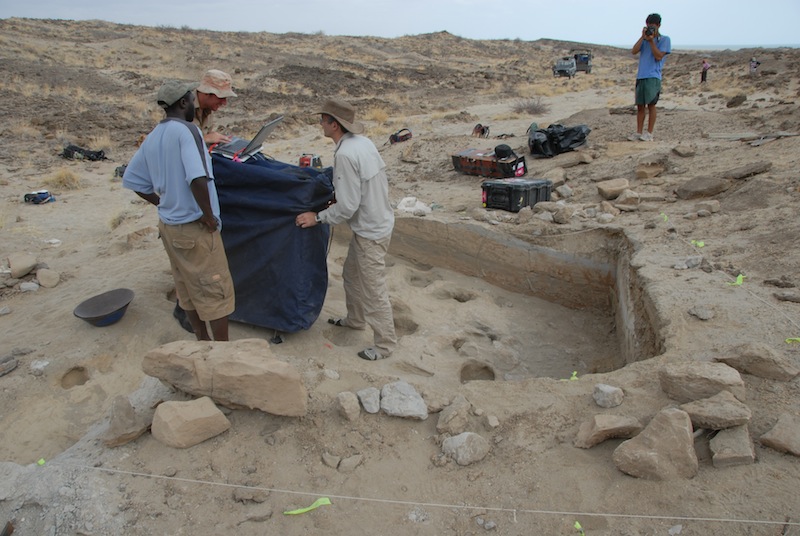

Recent excavations in Koobi Fora revealed dozens of large animal tracks, dating back to 1.4 million years ago, but a majority of the prints appear to have been left by a four-toed animal "bottom walking" in a shallow water body, study leader Matthew Bennett, of the United Kingdom's Bournemouth University, and his colleagues said.

Because of the size and shape of the prints, the team thinks the tracks could belong to adults and juveniles of the species Hippopotamus gorgops, which went extinct during the Ice Age, and perhaps the pygmy hippo species Hippopotamus aethiopicus.

At the time, the Lake Turkana area was much more fertile than it is today. The semi-arid environment had lots of shallow pools and channels, all feeding into larger lakes, and it supported a striking diversity of plants and animals, Bennett said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The hippo prints appear to have been pressed into fine sands and silts deposited on the floor of a shallow body of water, before being buried by a layer of coarser sand, likely during a small flood, Bennett explained in an email to Live Science.

Today's gliding hippos

To look for a modern comparison to these extinct animals, the researchers observed the swimming styles of two female common Nile hippopotamuses (Hippopotamus amphibius) through a glass tank at the Adventure Aquarium in Philadelphia.

Underwater, the Nile hippos would glide with their limbs folded beneath their bodies. They would occasionally scratch the bottom of the tank with one leg, dragging only their digits across the ground. Sometimes, the hippos would thrust upward, toward the water surface, using both of their hind legs. These movements were reflected in the shape of the ancient tracks, the researchers said.

Bennett said other swimming tracks of mammals likely have been uncovered but just haven't been recognized. These types of prints do not form clear sequences like footprints on land do, Bennett said. He also guessed that many researchers have tended to dismiss animal tracks in their quest for hominin footprints.

"[The hippo tracks] tell us about mammal locomotion in a near-zero-gravity environment," Bennett said in an email. "They show how different types of 'bottom walking' motion may be recorded as tracks. All of this helps us understand and interpret swim tracks made by much larger extinct animals, such as dinosaurs."

The findings were detailed online last month in the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus