Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

For the first time ever, astronomers may have spotted a moon circling an alien planet — though they'll probably never know for sure exactly what they've found.

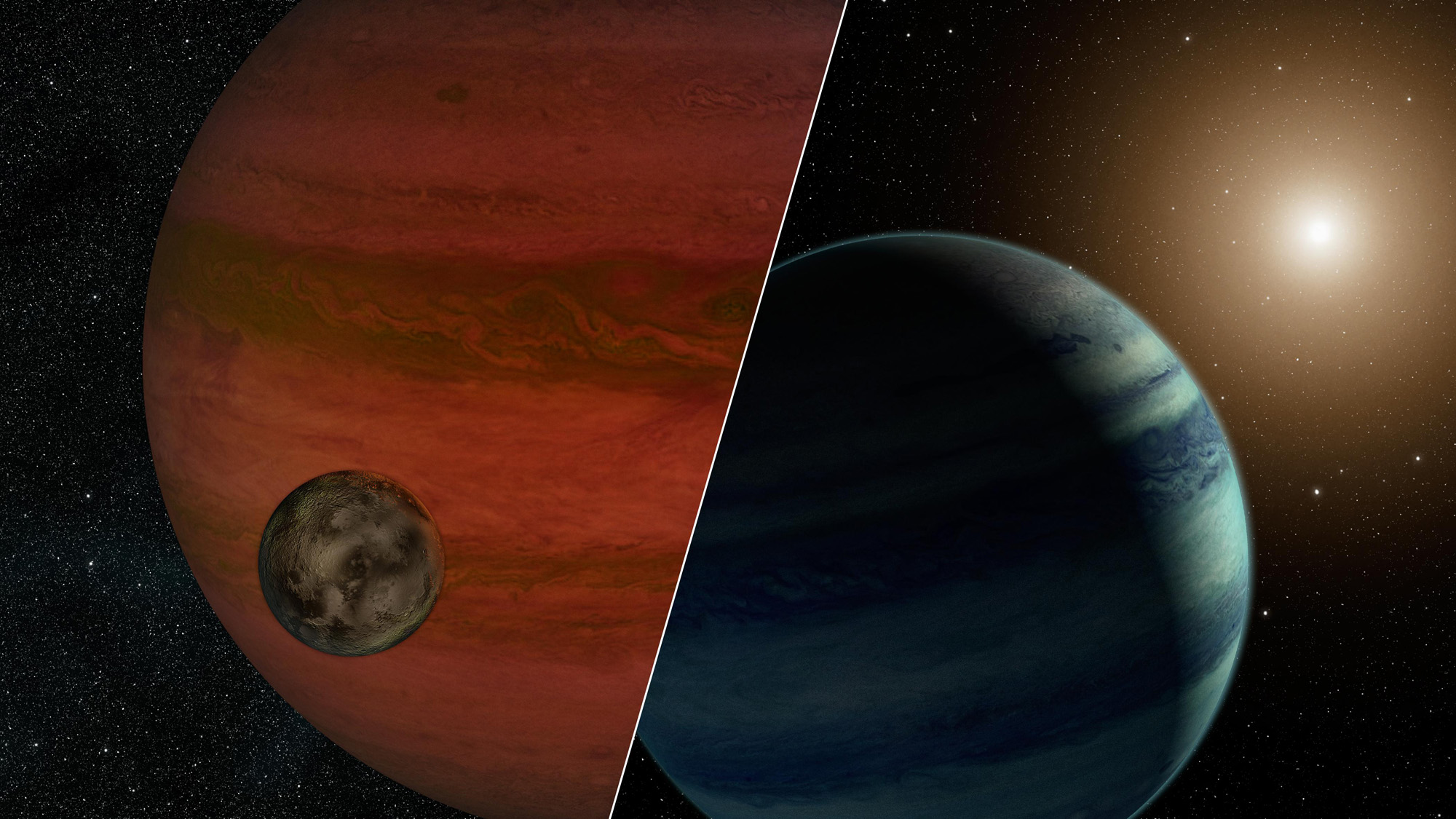

A team of scientists detected a pair of faraway objects that could be a giant Jupiter-like alien planet and a rocky exomoon flying freely through space, or a small dim star hosting a planet about 18 times more massive than Earth.

The astronomers used a technique called gravitational microlensing, watching what happens a big foreground object passes in front of a star from our perspective on Earth. The nearby body's gravitational field bends and magnifies the light from the distant star, acting like a lens. [The Strangest Alien Planets Ever (Gallery)]

Analyzing lensing events can reveal a great deal about the foreground object — for example, in the case of a star, whether it hosts a planet and, if so, how massive that world is compared to the star.

In the new study, the team observed one intriguing lensing event using telescopes in New Zealand and the Australian state of Tasmania. They determined that the foreground object has an orbiting companion about 0.05 percent as massive as itself.

"One possibility is for the lensing system to be a planet and its moon, which if true, would be a spectacular discovery of a totally new type of system," Wes Traub, chief scientist for NASA's Exoplanet Exploration Program office at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement.

"The researchers' models point to the moon solution, but if you simply look at what scenario is more likely in nature, the star solution wins," added Traub, who was not involved in the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team could solve the mystery if they knew how far away from Earth the lensing system, called MOA-2011-BLG-262, lies. If it's relatively nearby, MOA-2011-BLG-262 is probably a starless "rogue planet" and moon; a distant system would have to be as massive as a star to produce the same lensing effects, researchers said.

Unfortunately, the true identity of MOA-2011-BLG-262 will probably remain a mystery forever. Microlensing events are random encounters, so there will be no follow-up observations.

"We won't have a chance to observe the exomoon candidate again," study lead author David Bennett, of the University of Notre Dame, said in a statement. "But we can expect more unexpected finds like this."

And astronomers may be able to measure distances during future microlensing events using the principle of parallax, which describes how the position of an object appears to change when viewed from two different locations.

This strategy could work if observers manage to observe a lensing event with two widely spaced telescopes on Earth, or a ground-based scope and an instrument in orbit, such as NASA's Spitzer or Kepler space telescopes, researchers said.

Astronomers have discovered more than 1,700 alien planets to date, but they're still looking for their first confirmed exomoon.

The new study was led by the joint Japan-New Zealand-American Microlensing Observations in Astrophysics (MOA) and the Probing Lensing Anomalies NETwork (PLANET) programs. It appears in the Astrophysical Journal.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus