1,500-Year-Old Antarctic Moss Brought Back to Life

Moss frozen on an Antarctic island for more than 1,500 years was brought back to life in a British laboratory, researchers report.

The verdant growth marks the first time a plant has been resurrected after such a long freeze, the researchers said. "This is the very first instance we have of any plant or animal surviving [being frozen] for more than a couple of decades," said study co-author Peter Convey, an ecologist with the British Antarctic Survey.

There is potential for even longer cryopreservation, or survival by freezing, if mosses are blanketed by glaciers during a long ice age, the researchers think. Antarctica's oldest frozen mosses date back more than 5,000 years. [See Stunning Photos of Antarctic Ice]

The findings were published today (March 17) in the journal Current Biology.

Antarctic cryogenics

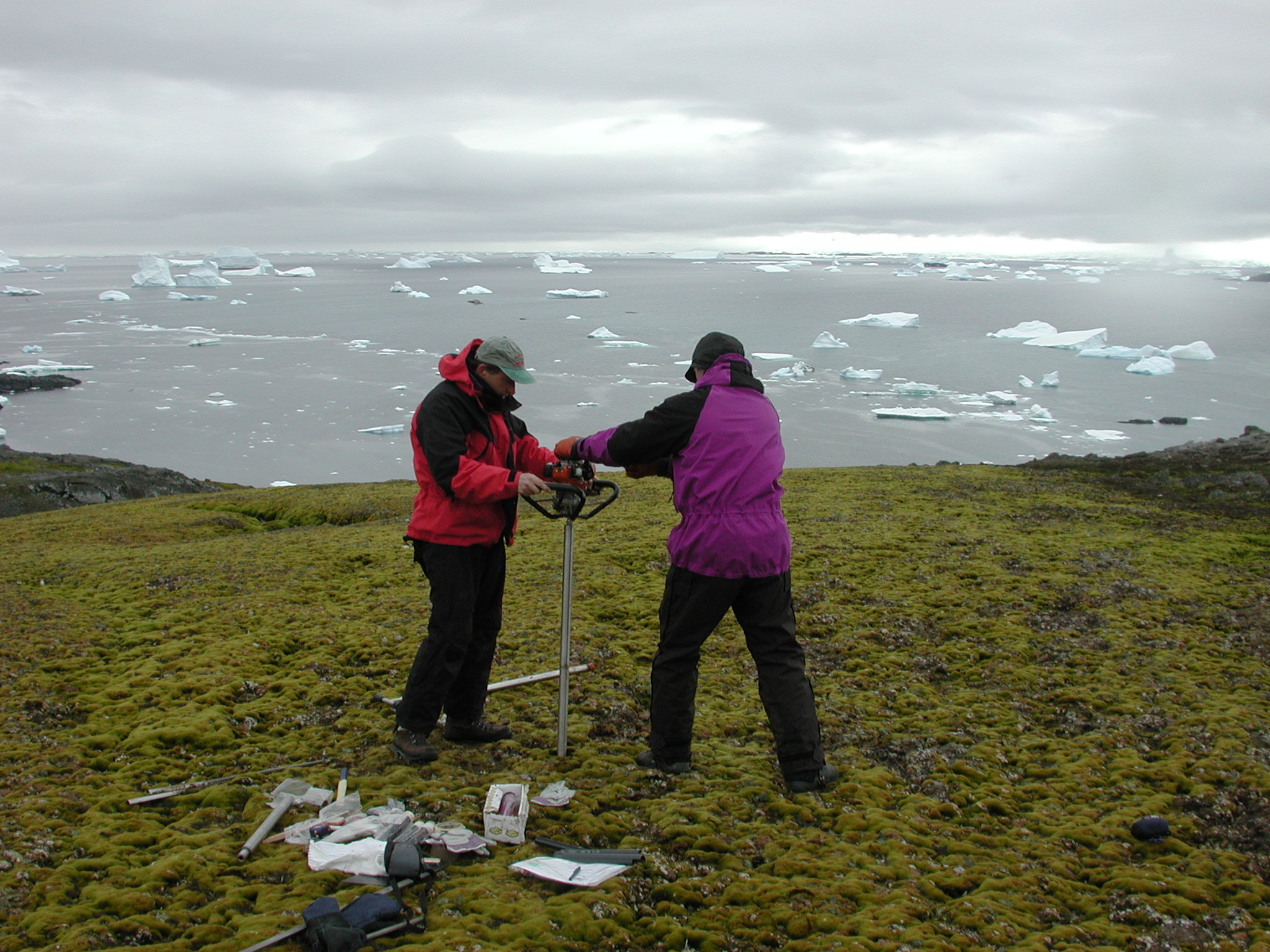

The moss comes from Signy Island, a small, glacier-covered island in the Drake Passage offshore of the Antarctic Peninsula. On Antarctic islands and the continent's coastline, thick, lush moss banks thrive on penguin poop and other bird droppings. The moss acts like tree rings, with layer upon layer of fuzzy clumps recording changing environmental conditions, such as wetter and drier climate shifts.

The moss resurrection came about after Convey and his colleagues noticed that old moss drilled out of permafrost on Signy Island looked remarkably fresh. The deeper layers didn't decay into brown peat (a type of decaying organic matter), as they would in warmer spots.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"In North America, you've got living moss on top of a dead peat base. It's black, wet sticky stuff," Convey told Live Science. "If you look at these cores [from Signy Island], the base is very well-preserved. They've got a very nice set of shoots."

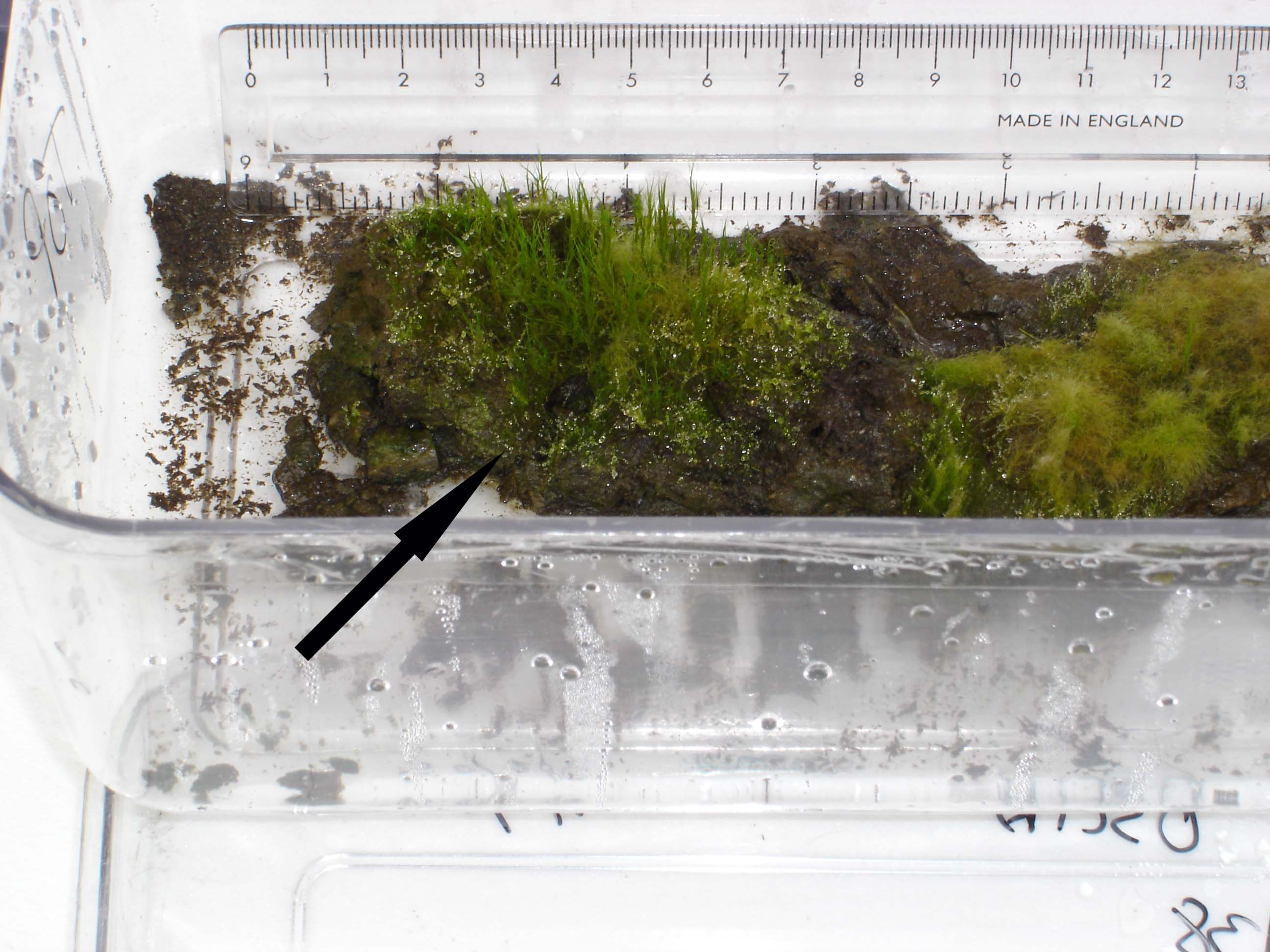

To test whether the Antarctic moss would regrow, the researchers punched into the permanently frozen soil beneath the living moss, removing cores that contained frozen soil, ice and plants. To prevent contamination, they quickly wrapped the mossy cylinders in plastic and shipped them back to Britain at freezing temperatures. In the laboratory, the team sliced up the core and grew new moss in an incubator, directly from shoots preserved in the permafrost. They also carbon-dated the different layers, which provided an age estimate for revived moss shoots.

The oldest moss in the core first grew between 1,697 and 1,533 years ago, when the Mayan empire was at its height and the terror of Attila the Hun was ending in Europe and Central Asia. In the lab, this moss sent out new shoots from its rootlike "rhizoids," the researchers report. Because the growth comes directly from the preserved moss, and is the same species, it's unlikely that spores from elsewhere contaminated the samples, Convey said. (Antarctic mosses don't make spores.)

"We can't be certain there is no contamination, but we have very strong circumstantial evidence," he said. "Under a microscope, you can see the new shoot growing out of the old shoot. It is very firmly connected."

Survival on ice

Many species other than mosses have unique survival strategies for the cold, such as hibernation in bears or bugs with built-in antifreeze — proteins that prevent destructive ice crystal growth. Others, including plants, simply endure freezing. Microbes and plant genetic material have been resurrected from ancient Siberia permafrost, more than 20,000 years old. But until now, scientists had hard evidence only of creatures surviving about 20 years without water or warmth, Convey said.

Researchers recently suggested that Antarctica's volcanoes radiate enough heat to provide refuges for life during Earth's coldest climate swings, when ice ages send the continent's glaciers far out to sea and ice covers the land. Species such as moss and bugs can't escape to warmer climates when the ice advances, because they're trapped by the vast Southern Ocean. Now, there's another survival mechanism for mosses, Convey said.

"In Antarctica, you've got survival challenges over a lot of different time scales," he said. "If you can get to 1,500 years, what's the possibility of surviving an entire glacial cycle?"

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus