Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The ancestors of Native Americans may have lived on and around the Bering Strait for about 10,000 years before streaming into the Americas, researchers argue.

In the new Perspectives article, published today (Feb. 27) in the journal Science, the researchers compile existing data to support the idea, known as the Beringia standstill hypothesis.

Among that evidence is genetic data showing that founding populations of Native Americans diverged from their Asian ancestors more than 25,000 years ago. In addition, land in the region of the Bering Strait teemed with grasses to support big game (for food) and woody shrubs to burn in the cold climate, supporting a hard-scrabble existence for ancient people. [In Images: Ancient Beasts of the Arctic]

Given the hypothesis, archaeologists should look in regions of Alaska and the Russian Far East for traces of these ancient people's settlements, the authors argue.

Genetic differences

A dominant theory suggests the ancestors of Native Americans crossed the Bering Strait about 15,000 years ago and quickly colonized North America, and then South America.

But in 2007, genetics researchers found that almost all Native Americans in North and South America shared genetic mutations in their mitochondrial DNA, which is the genetic information that's carried in the cytoplasm of the egg and passed on through the maternal line. None of the mutations show up in Asian populations from which the Native American ancestors diverged, said study co-author John Hoffecker, an archaeologist and paleoecologist at the University of Colorado, Boulder. (Genetic evidence also suggests that some northern populations, such as the Inuit, likely came over in a second wave separate from the ancestors of Native Americans.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Given the rate at which such mutations occur, the findings suggested a single Native American founding population must have been isolated from its Asian ancestors for thousands of years before dispersing throughout the Americas.

Shrubby landscape

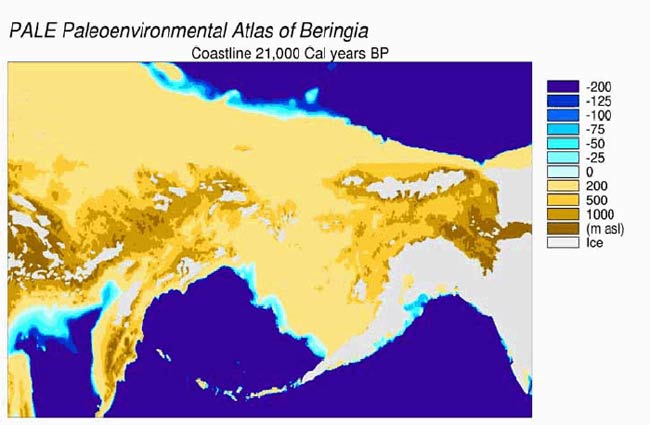

Other evidence fits the genetic data. Between 28,000 and 18,000 years ago, glaciers covered much of the Americas and northern Asia, blocking human migration into North America.

But in the 1930s, Swedish botanist Eric Hultén proposed that the region known as Beringia, which includes the land bridge now submerged under the Bering Strait, was a refuge for shrubby tundra plants. Pollen, insects and other plant remains taken from sediments beneath the Bering Sea confirmed this picture. [Photos: Amazing Creatures of the Bering Sea]

The outer portions of Beringia, in what is now Alaska and the Russian Far East, were likely drier grassland steppes where woolly mammoths, saber-toothed tigers and other big game grazed, Hoffecker said.

This region would have had two crucial resources that other Arctic areas didn't: woody plants to start fires and animals to hunt, Hoffecker said.

"The central part of Beringia was probably the mildest, most comfortable place to live at high latitudes during the last glacial maximum," Hoffecker told Live Science. "It's the most logical place for a group of people to hunker down."

Once the glaciers melted, only then did the Beringian inhabitants stream into North America, traveling along the coastline and into the interior through ice-free passageways, Hoffecker said.

No archaeological sites

While it's possible that the ancestors of Native Americans were isolated in Beringia for 10,000 years, the standstill hypothesis is hobbled by one detail: a lack of archaeological evidence prior to 15,000 years ago, said David Meltzer, an anthropologist at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, who was not an author on the new paper.

Some of the archaeological sites would have been washed away as the Bering Strait flooded, but "at least half of Beringia is still above water, so where are the sites?" Meltzer told Live Science. "If people were there for 10,000 years, you'd surely see evidence for them by now."

But the hypothesis is still compelling, said G. Richard Scott, an anthropologist at the University of Nevada, Reno, who was not involved in the work.

"The best explanation for why American Indians are so radically different from northeast Asians is that they just didn't stream over in the late Pleistocene [epoch]; they were stuck up there in the Arctic for maybe 10,000 or 15,000 years," Scott said.

The paper gives archaeologists an impetus to look for the potential lost sites of this occupation in Russia and Alaska, he added.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus