Antarctica's Soggy Bottom: New Lakes & Streams Found

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

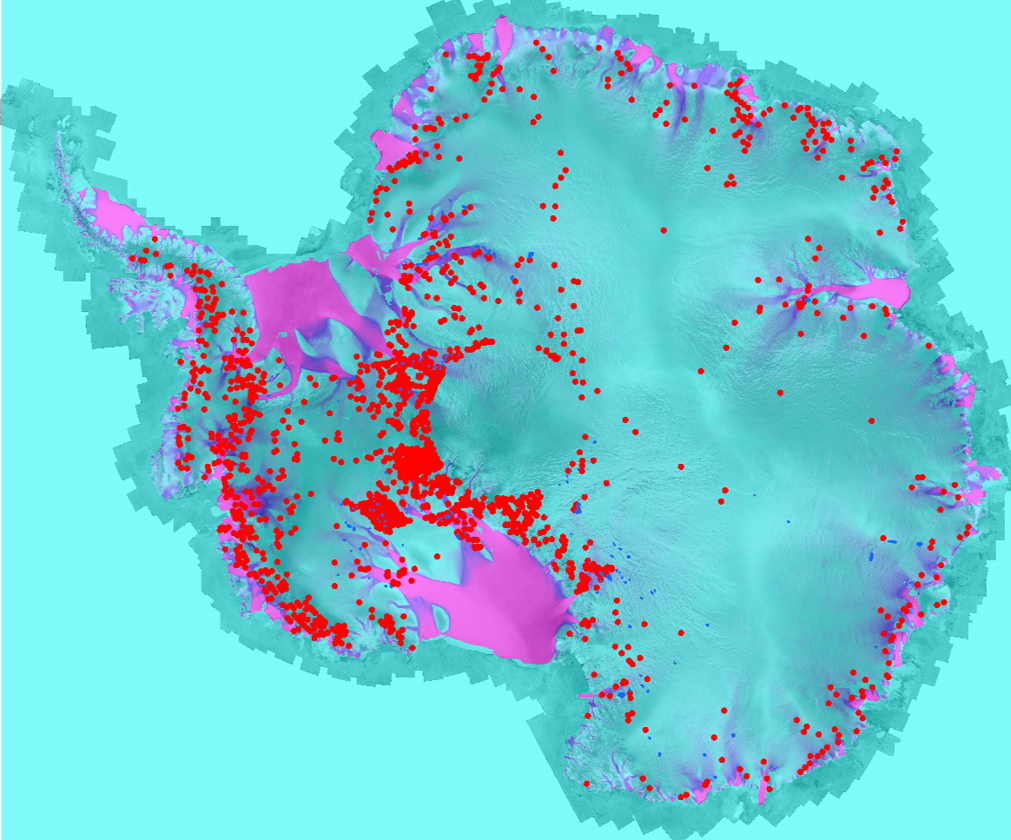

Dimples in Antarctica's vast ice sheet frequently pop up and down like creatures in the arcade game "Whac-A-Mole" — a sign that water is forcing its way through a vast network of channels and lakes under the ice, researchers said last week at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

Scientists reported new evidence of many previously unknown "active" lakes and hollows, which fill and drain like a bathtub, as well as better maps of the drainages connecting these basins.

"We have identified thousands of locations where we infer hydrologic change in Antarctica," Greg Babonis, a graduate student in glaciology at SUNY Buffalo, said Dec. 11.

Water is a critical player in how quickly Antarctica's ice sheets slip toward the sea. Understanding where water flows under the ice will help modelers better predict the future behavior of the continent's vast ice rivers, and their response to climate change, Babonis said.

Babonis found about 120,000 locations on Antarctica's icy surface that changed rapidly between 2003 and 2008, from NASA's ICESat satellite data. The points show where ice either thickened or thinned (moving up or down), he said. (Water can lift the ice, and its absence will make the surface sink.) After narrowing down the signals by looking for rapid, cyclic changes and removing snow effects, Babonis ended up with about 5,000 locations that hint at water beneath the ice. Some of the points cluster over known subglacial lakes, such as Lake Whillans or Lake Vostok, but many others could signal newly discovered water bodies and streams, Babonis said.

"In many cases, our work indicates lakes may be larger, more numerous and more hydrologically complex," Babonis told LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet. "And in other cases where we think there should be lakes, we find what is probably a stream." [Extreme Antarctica: Amazing Photos of Lake Ellsworth]

How the water flows

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The exact nature of Antarctica's streams and channels is still unknown, however. The water could flow through narrow, deep streams and rivers, or broad, connected shallow channels, more like a swamp. And some of the lakes could be temporary ponds, where water gets trapped on its path to the sea.

Glaciologist Martin Siegert thinks there may be more water flowing beneath the ice than previously thought, because one of the best tools for peering beneath the ice — echo-sounding radar — seems to miss some of the shallow water bodies that make the ice surface move up and down, he said Dec. 12. "If you didn't know it was there, you wouldn't be able to spot it," said Siegert, of the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom. "I think it's time to start again with our thinking about [water]. I think all bets are off."

Siegert led a targeted search for active subglacial lakes under West Antarctica's Marie Byrd Land, to better understand why water was hiding from radar. The team discovered a three-tier lake system, according to surface elevation changes. But a close-up look at one lake, called Institute E2, revealed an unusual shallow feature: The water was perhaps less than 20 feet (6 meters) deep. Instead of finding a lake basin, the team discovered the water was "draped" on an uphill surface, suggesting the lake is actually just temporarily ponded water within a drainage network, Siegert said. (Pressure from the overlying ice drives the water uphill.)

About 150 active subglacial lakes have been identified in Antarctica, where the surface level changes with time. In all, scientists have counted 379 lakes buried beneath the continent's enormous ice sheet.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us OurAmazingPlanet @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus